Whether matching drivers with riders or landlords with lodgers, digital platforms like Uber and AirBnB push the marginal cost of matching supply and demand to an unprecedented low. Large infrastructure projects like China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative - which aims at more closely linking the two ends of Eurasia, as well as Africa and Oceania - could create an opportunity to alter the future of Central Asia’s agriculture, if food supply and demand can be matched more efficiently.

The key to this future? The backhaul.

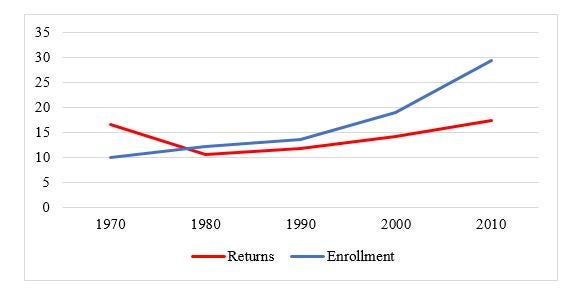

In transportation, backhaul is defined as cargo that is hauled back from its destination to its origin. Since it costs almost as much to move an empty vehicle as a fully loaded one, filling a vehicle on the return trip makes a lot of economic sense. Consider the wasted space of approximately 8 million 20-foot equivalent containers that made the return trip to Asia - mostly to China – between 1995 and 2015 (see graph below). They were largely filled with air. The way things are going, a lot more air will be moved back to China in the next decade.

China’s food demand is rising and will continue to do so in the years to come. A recent study shows that, as China’s population increases in size and wealth, demand for high quality meats, dairy, fruits, and vegetables is rapidly outpacing domestic production. By 2030, Chinese meat demand will increase by 20% to 110 million tons. Meanwhile, demand for dairy will rise by 66 % to 116 million tons, and fruits and vegetables by 30% to 590 million tons.

This has substantial implications for Central Asia’s agriculture. Central Asia’s land per capita endowment is 5 times higher than China’s - 0.5 versus 0.1 hectares per capita. Furthermore, Central Asia’s agricultural productivity is on the rise as antiquated farming practices are modernized and new trade policies unlock the region’s potential as a prolific agricultural exporter. Add to that, people say that it is cheaper to ship wheat from Vancouver to Urumqi (9,233km) than from Almaty to Urumqi (869 km), and the challenges and opportunities become clear. Yet, digital technologies can potentially reduce the costs of matching Central Asian farmers with Chinese consumers along the new Silk Road and make Central Asia’s agriculture more competitive.

Can a global Uber Eats-like service fill all the empty containers and offer Central Asia new opportunities to reach China’s markets? This idea is not new.

In 2014, Alibaba launched its rural integration initiative, based on a simple principle: loaded trucks go out to the countryside, loaded trucks come back from the countryside. In this case, Rural Taobao gave 150,000 villages access to a dynamic online marketplace through which farmers could purchase manufactured goods from the urban centers of the east and sell back agricultural goods. Alibaba’s “Cainiao” platform optimizes the distribution of parcels, substantially decreasing transportation costs. Last November on Singles Day, one of China’s largest shopping holidays, rural farmers sold 450-million-yuan worth of agricultural goods through the platform, whereas 3 years ago that amount was close to zero.

If used strategically, China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative could present an opportunity for Central Asia’s 10.7 million farmers. What role does the public sector have in making this simple concept a reality and in helping Central Asian agriculture flourish? Rather than wait and wish we could travel back in time to change the future, stakeholders should seize the opportunity and act now. Come join the debate (in the comments section below).

-------------------------------

We hope to crowd-in some of the world’s best minds to participate in a global conversation on food and technology through the “What’s cooking? Rethinking farm and food policy in the digital age” blog series. We invite people with diverse backgrounds and perspectives to join us and share their comments.

Join the Conversation