For the first time in history, more than half the human population lives in cities, and the vast majority of these people are poor. In Africa and Asia, the urban population is expected to increase between 30-50% between 2000 and 2020. This shift has led to a range of new public health problems, among them road traffic safety. Road crashes are the number 1 killer among those aged 15-29, and the 8th leading cause of death worldwide. The deadly impact from accidents is aggravated by pollution from vehicles, which now contributes to six of the top 10 causes of death globally.

Globalization of trade, travel, migration, and information goes increasingly hand-in-hand with globalization of health risks, including infectious diseases, lapses in food safety, and unhealthy lifestyles. Consumption patterns in low-and middle-income countries unfortunately respond to aggressive marketing and easy availability of products, such as tobacco, sugared drinks, processed food, alcohol, and baby formula.

People greatly benefit from urbanization and easy mobility, but it also means that now a novel pathogen can spread from a remote rural village to cities on all continents within 36 hours. These risks are known, but few policymakers are aware of them. So far, responses are lagging and are not commensurate with the threats.

There have been major achievements in public health over the past decades, improving the health of people everywhere. But now, as we are well into the second decade of the 21st century, public health challenges call for battles that are relevant to changed circumstances.

Mostly, these battles will have to be fought outside the traditional confines of clinics, hospitals and dispensaries of the health sector. Indeed, business as usual is no longer an option because it will lead to an unacceptable disease burden. As Tim Evans, the World Bank’s Director for Health, Nutrition and Population, noted recently, the “white coat and stethoscope are no longer enough.”

Ministers of health will need to recognize that in their traditional roles they cannot address a growing range of health issues. Indeed, bringing other sectors “under the tent” should become the norm, rather than the exception. The urban space is a logical place to start because the concentration of large numbers of people offers a natural opportunity for more effective and efficient public health actions. So, let’s talk to the mayors!

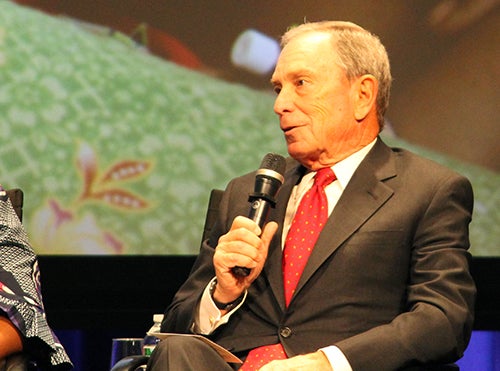

Take, for example, what former Mayor Michael Bloomberg did in New York City during his tenure (2002-2013). He deployed a “big tent planning approach” by bringing together several city agencies across sectors. Data-driven policies and plans backed by strong regulations made a huge difference, at a decidedly modest cost relative to the benefits that have already been realized and that will continue into the future.

A combination of multi-sector actors, strong policies, enforcement measures and action on tobacco, obesity, and air quality, to name a few, delivered substantial results:

- A significant drop in smoking among adults, from 22% in 2002 to 14% in 2010;

- Reductions in heart disease and cancer;

- A decline in prevalence of obesity among public elementary school students, from 21.9% in 2006 to 20.7% in 2011;

- A decline in the proportion of people consuming sugary drinks, from 36% in 2007 to 32% 2009. (Notably, daily consumption of one or more sugar-sweetened sodas among teenagers dropped from 28% in 2005 to 22% 2009.); and

- An improvement in air quality, as seen in a decrease in 2.5 particulate matter, by 23% from 2005 to 2011.

The administration of Mayor Bloomberg, and other mayors around the world, has shown how public health measures are a gift to the entire population, and one that keeps on giving. Take Argentina, for example. Through a territorial approach including a network of healthy municipalities founded in 2001, several initiatives/actions are being implemented or under development to address non-communicable diseases and their risk factors, such as the certification of smoke-free institutions and certified bakeries under a program called “less salt, more life.”

So, to my colleagues in global health: the next time you’re traveling for work in a large city, make sure you stop by the mayor’s office.

Follow the World Bank health team on Twitter: @worldbankhealth.

Join the Conversation