We recently participated in an event held in Lima by Peru’s Ministry of Health and the Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University for the launching of a new report that assesses the initial results at the municipal level of the mental health services reform in the country.

Compelling evidence showing that the community-based initiatives to improve mental health care in Peru are helping close a major access gap that exists in most countries was shared.

So, what are the main pillars of the Peruvian mental health reform process and its initial impact?

Knowledge of the health problem and service coverage. A critical element for the formulation of policy and organizational reform in any health system is to have a well-documented understanding of the nature and characteristics of the burden of disease and service coverage gaps. In Peru, burden of disease epidemiological assessments documented that each year, one in five Peruvians is affected by a mental disorder, one in ten women in a partnership or union is subject to physical or sexual violence by a partner, and one in ten children has a mental disorder. When combining mortality and morbidity estimates, mental health and substance use disorders are found to be the leading cause of years of life lost and years lived with disability in the country. Of all chronic diseases in Peru, mental health problems also account for the greatest economic costs, far outstripping cardiovascular diseases, cancer, or diabetes. Mental and substance use disorders are highest among the poor and marginalized, and those victims of violence, further reducing their economic productivity and slowing the country’s progress towards inclusive social wellbeing and prosperity.

As in most countries, the provision of mental health care has remained largely concentrated in psychiatric hospitals. This model of care, that often serves as “warehouses for the mentally ill”, is associated with large, persistent care gaps. In 2012, before the introduction of mental health care reforms, just 12 percent of Peruvians estimated to need mental health services received them.

New legal and regulatory framework. Peru’s Mental Health Law 29889, enacted in 2012, provides the legal framework for the mental health care reform process. The National Plan for the Strengthening of Community Mental Health 2018-2021, and other normative document formulated by the Ministry of Health, are guiding scaled up implementation of the reform across the country.

Paradigm change in the organization and delivery of services. The network of community mental health centers (CSMCs), as established by Law 29880, is the most important component of Peru’s mental health care reform, bringing service provision out of psychiatric hospitals into local settings, where providers engage patients, families and communities as active partners. Since 2015, 131 CSMCs have been established and are in operation; by 2021, the Ministry of Health expects to expand the network to include 281 centers nationwide, and 30 units to address the needs of children who are victims of violence. Staffed by inter-disciplinary teams of clinical and social workers, the centers provide specialized ambulatory services to children and adolescents; adults and the elderly; and persons with substance use disorders. By providing training and in-service mentoring to general primary health care providers, specialized mental health teams at the CSMCs also support the integration of mental health care services into primary care. By 2018, 524 general health facilities are estimated to have trained personnel to deal with mental health conditions; the Ministry of Health target is to increase the number of general health facilities with trained personnel to 1124.

Complementing the services provided by the CSMC, 50 protected halfway houses (“hogares protegidos”) have been established to provide temporary residential services to people with serious mental disorders who have been discharged from hospitals and have weak family support systems, and to women who are victims of domestic violence. The Ministry of Health target by 2021 is to have in operation 170 protected halfway houses. The halfway house uses a model of residential care that respects residents’ human rights and places minimal restrictions on their personal freedoms, thus facilitating their reintegration into the community. At the same time, while they enjoy considerable autonomy, residents are carefully monitored and mentored by staff present in the facility around the clock.

In addition to first-level facilities like CSMCs and halfway houses, the operation of the community-based mental health care network in Peru includes an important role for general hospitals at the local level. Following WHO norms, short-term inpatient wards have been established in 32 general hospitals in the country, to provide 24-hour medical care and supervision for patients with acute mental disorders, in the same way that these facilities manage acute physical health conditions. By 2021, the target of the Ministry of Health is to have mental health wards in 62 hospitals.

In parallel with the expansion of the community-based mental health services model, the process of reforming and in some cases the closing of specialized psychiatric hospitals has begun in different regions of the country in accordance with the deinstitutionalization process and to reallocate budget to support the expansion of community-based mental health care.

Innovative health financing model. The inclusion of mental health services as part of the benefits package offered under Peru’s Integrated Health Insurance scheme (SIS) was a crucial step towards the achievement of mental health parity in the health system. This measure, which was complemented by the development of a revised reimbursement fee schedule to cover the cost of services provision at community mental health facilities and specialized psychiatric hospitals, spurred the significant growth in the provision of mental health services. It also helped reduce patients’ out-of-pocket payments for mental health services from 94 percent in 2013 to 32 percent in 2016. Also, a 10-year results-based budget program, approved by the Ministry of Economy and Finance in 2014 exclusively for mental healthcare reform, is helping its implementation and scalability. Similar to the SIS, the Peruvian Ministry of Economy and Finance assigns budgets based on the attainment of predetermined indicators, known as Presupuesto por Resultado (PpR) or pay-for-performance.

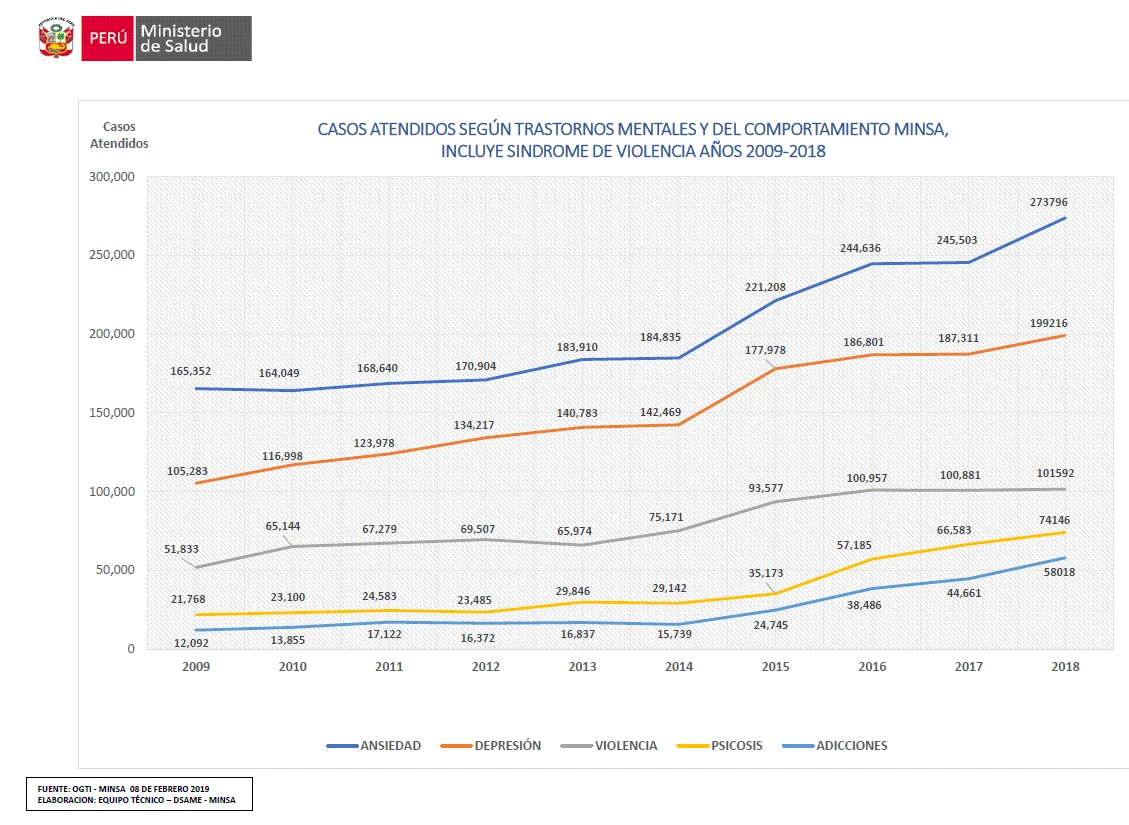

Gradual but significant coverage expansion. According to Ministry of Health data, coverage of mental health services has gradually increased in Peru over the past decade, from a low 9.9 percent of people who require care to 26 percent in 2018. As shown in Figure 1, the total number of cases attended for different mental health and substance use disorders accelerated after the 2013 reform reaching more than 1 million cases in 2018. By 2021, the Ministry of Health target is to increase coverage to 64 percent of the population in need or about 3.2 million people. Also, evidence from the Carabayllo district, shows that the community-based mental health services is a good value for money alternative to institutionalized care. The average unit cost per outpatient consultations at specialized mental health hospitals was estimated at about US$59, while the cost for standard outpatient consultations at a CSMC is US$12.

Figure 1: Number of cases treated for mental and substance use disorders, including violence-related cases, 2009-2018, Peru

The way forward. The Peruvian experience clearly shows that the global fight to transform mental health, can be won. While significant policy and institutional cultural challenges remain, we left Lima convinced that the progress achieved thus far in Peru, serves to demonstrate that a combination of political will, a paradigm shift in the way services are organized and delivered, domestic resources mobilization and innovative allocation modalities that incentivize the reform process, and active involvement of local governments, affected people, families, and communities, are the indispensable factors to help countries achieve mental health parity.

Related:

Peruvian Mental Health Reform: A Framework for Scaling-up Mental Health Services

World Bank Group Global Mental Health Initiative

Join the Conversation