In 17 th century India, the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan built an immense tomb of white marble—known as the Taj Mahal—in memory of his wife, Mumtaz Mahal, who died during the birth of their 14 th child. The mausoleum, revered for its beauty, also serves as a sad reminder that maternal deaths have forever plagued humanity.

Maternal deaths, today an avoidable tragedy, still occur at relatively high rates in many developing countries, despite a steep reduction in maternal mortality worldwide since 1990. Globally, about 289,000 women died in 2013 from pregnancy or birth-related causes. Only two regions, sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, accounted for 85% of global maternal deaths.

South Asia, where 24% of global maternal deaths occurred, is home to 1.6 billion people across eight countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

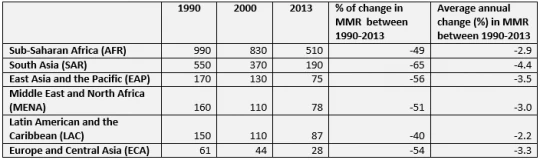

Data released earlier this year by the World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank Group show that South Asia significantly reduced its maternal mortality ratio (MMR) per 100,000 live births, from 550 in 1990 to 190 per 100,000 live births in 2013, marking a decline of 65%, equivalent to 4.4% per annum. This is the largest MMR reduction achieved among the six world regions (Table 1).

Table 1: Trends in global maternal mortality by region, 1990-2013

Source: Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013 - WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank estimates, 2014.

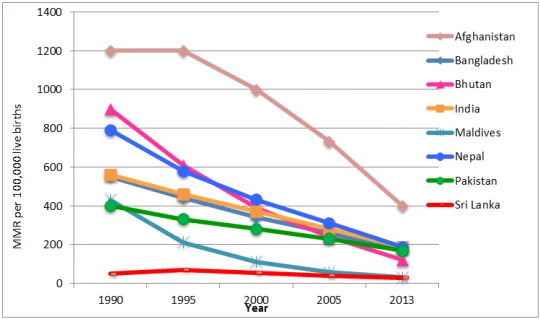

Though all South Asian countries have contributed toward the global reduction in MMR, data point to several country success stories that might be instructive for other countries working to achieve Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5, to reduce the MMR by three-quarters from 1990 to 2015 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Trends in MMR among SAR countries, 1990-2013

Source: Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013 - WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank estimates, 2014.

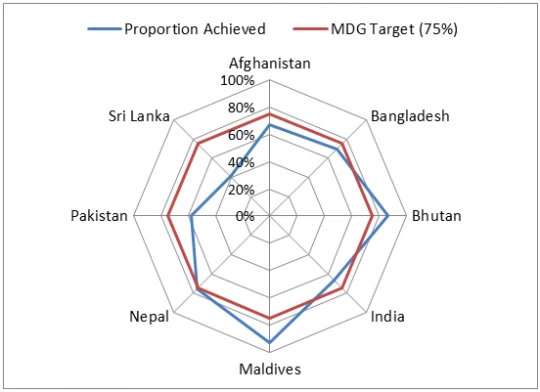

First, three countries, Bhutan, Maldives, and Nepal, are among the 10 countries worldwide that have reduced maternal deaths by 75% and above thus already achieved MDG5 (Figure 2).

Nepal, for example, has made significant progress in reducing MMR due to a concerted, national effort comprised of several maternal and child health interventions. A landlocked and low-income country with a per capita GNI of US$1,289 (2012), Nepal has prioritized family planning and maternal and child health at the national level since the mid-1960s. More recently, the government has focused on increasing access and use of health services among the most vulnerable populations. Key interventions include: (1) adoption of a community-based approach to service delivery, (2) provision of subsidized or free care for maternal and child health services, and (3) introduction of female community health volunteers. Improvements in socioeconomic status have also contributed to better health outcomes in Nepal – the country has reduced poverty by 2.5 percentage points yearly since 2004.

Figure 2: Proportion reduction in maternal mortality ratio

Source: Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013 - WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank estimates, 2014.

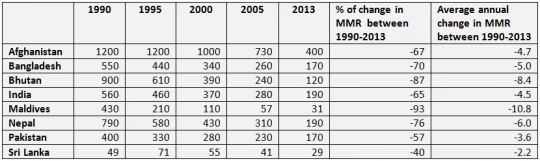

Second, three countries -- Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and India -- have achieved remarkable reductions in MMR of 65% and above (Table 2).

A decade ago, Bangladesh was off-track to achieve MDG5 but eventually achieved a 70% reduction in MMR, thus bringing it back ‘on track’, with annual MMR reductions of 5%, one of the fastest rates of reduction among low-income countries.

The decrease in MMR in Bangladesh appears to have been the result of factors both within and outside the health sector. Within the health sector, a strong family planning program was the main catalyst for accelerated fertility decline and thus reduction of MMR. Programs aiming to improve utilization of maternal care services, particularly by robust non-governmental organizations, and access to Emergency Obstetric Care, have also contributed to the decline.

Outside the health sector, Bangladesh has been a pioneer in areas such as girls’ education, employment of women and micro-credit programs, all of which have had an impact on lowering MMR as well.

Table 2: Trends in MMR among SAR countries, 1990-2013

Source: Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013 - WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank estimates, 2014.

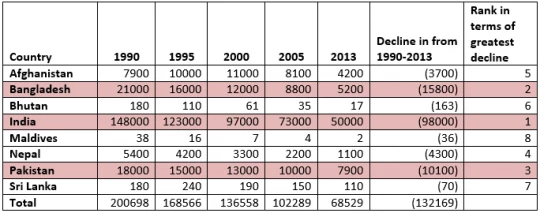

Third, three countries contributed the most to the region-wide decline in the number of maternal deaths : India (74.1%), Bangladesh (12%), and Pakistan (7.6%) (Table 3). Within India, three states: Uttar Pradesh/Uttaranchal, Bihar/Jharkhand, and Rajasthan contributed more than 50% of the total of India’s decline in maternal deaths.

While it is unlikely that Pakistan will achieve MDG 5 by 2015, the country has introduced several maternal and child interventions that are instructive. Female community health workers, known as Lady Health Workers, have been highly effective in reaching women in rural and poor, urban areas, many of whom have limited mobility due to cultural restrictions. In some regions, women are not allowed to leave the house by themselves; they must be accompanied by a male or other family member.

As of 2013, Lady Health Workers covered 60% of the rural Pakistani population, providing an important link between the community and the health system, and increasing uptake of health services. A recent, independent evaluation found that Lady Health Workers have a positive impact on uptake of family planning and antenatal care.

Table 3: Trends in the number of maternal deaths among SAR countries, 1990-2013

Source: (1) Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2013 - WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank estimates, 2014; (2) World Development Indicators, the World Bank.

Remaining challenges

Despite its accelerated MMR reduction, Afghanistan remains one of the world’s “high MMR” countries, with 400 per 100,000 live births.

Pakistan’s MMR is the second highest in South Asia, with the smallest rate of reduction, after Afghanistan. Slow fertility reduction, as well as health system-related deficits, including lack of trained health staff and inadequate low availability of emergency obstetric care, has contributed to Pakistan’s relatively slow progress. The country has also been slow to advance gender equality in education and labor participation.

In addition, despite its accelerated MMR reduction, India still accounts for more than two-thirds of total maternal deaths in the region, or 17% of global maternal deaths, and shows wide disparity in maternal mortality across states and income groups.

Across South Asia, factors hindering reduction in MMR include high early marriage and pregnancy rates in some countries; inequity in access to maternal health services; and chronic malnutrition, a frequent underlying cause of maternal deaths, even for those in wealthier populations.

Finally, gender inequality persists in every domain of South Asian societies and has a daily impact on the lives and health of women.

While the unfortunate tragedy of Mumtaz Mahal still occurs in some areas of South Asia, tremendous progress in reducing maternal mortality over the last two decades offers hope. As several countries in the region have shown, innovative approaches can help save lives while giving life!

Follow the World Bank Health team on Twitter: @WBG_Health

Related

World Bank and Health

World Bank and South Asia

Publication Series: Maternal and Reproductive Health in South Asia

Join the Conversation