Remittances sent by migrant workers to developing countries have soared in the past two decades. According to the World Development Indicators, workers’ remittances to developing countries were just US$47 billion in 1980 (in constant 2011 dollars). After barely rising by 1990 ($49 billion), they

doubled by 2000 ($102 billion), and from there,

tripled by 2010 ($321 billion). The World Bank’s prospects group’s

latest estimates are that remittances to developing countries reached $404 billion (in nominal terms) in 2013, and are predicted to grow to $516 billion by 2016.

These amounts now greatly exceed the total sum of all aid flows to developing countries, and such big numbers have brought increasing policy attention to the impact of remittances on sending country economies, and various proposals for policy actions to increase the development impacts of remittances. But it has also asked policymakers and some researchers to ask why have such rapid increases in remittances not resulted in noticeable improvements in economic growth in the recipient countries?

In a new working paper with Michael Clemens of the Center for Global Development, we investigate several reasons for the lack of apparent impact of remittances on economic growth. In today’s post I want to focus on one major reason: our claim that growth rates are vastly overstated.

The large overstating of remittance growth

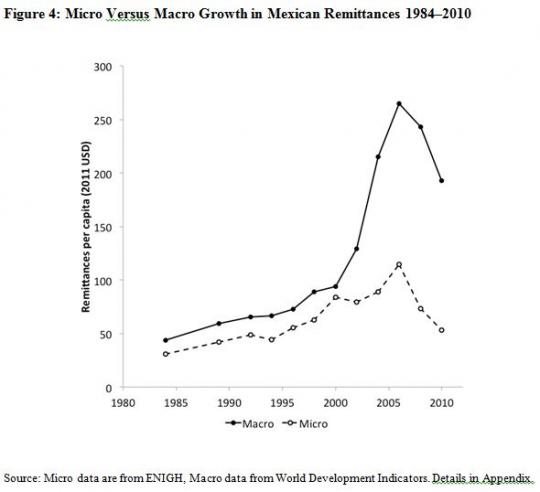

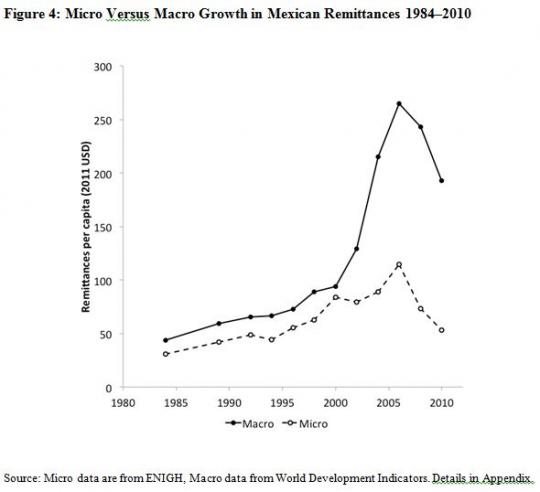

The solid line in the figure below shows macro data on remittances for Mexico. We see steady growth from the mid-1980s to around 2000, then incredibly rapid growth following this. The dotted line shows remittances for Mexico as measured in Mexican household surveys. The micro and macro data track each other very closely in growth rates until 2000/2001, and then diverge from each other, with much faster growth in the macro data in the 2000s.

We find the same pattern in several other countries. So which of these series is correct?

We note first that the divergence in the two series in Mexico occurs at the same time as a law change affecting reporting in the macro data: before 2002 only commercial banks reported their remittance transactions to Mexico’s central bank, but then in 2002 a new regulation required all money transfer companies to register at the central bank and report their remittance transactions on a monthly basis. So suddenly measured macro remittances soar as a result. This suggests that in this case at least, much of the growth in remittances in the macro data is due to changes in measurement. Is this a general phenomenon?

Understanding macro data on remittances

Macro data on remittances come from balance of payments data provided by each country to the IMF. The underlying data that feeds into these aggregates comes from central banks in each individual country. They typically require banks, money transfer operators and other institutions to provide reports on the transactions they process. But this coverage is often partial, and separating remittance transactions from other financial flows can be challenging. As a result, it has long been recognized that macro data on remittances are noisy, but we haven’t seen any previous attempts that attempt to quantify what this means for growth.

We can write:

Global remittances to developing countries = The number of migrants from developing countries*Average earnings per migrant*share of income each migrant remits.

As a result, if we assume that migrants haven’t changed the share of income they remit (an assumption we provide some empirical evidence for in the paper, and also discuss robustness to), then we can write:

Growth in remittances = Growth in migrants + Growth in Migrant earnings + Growth in migrants*Growth in migrant earnings

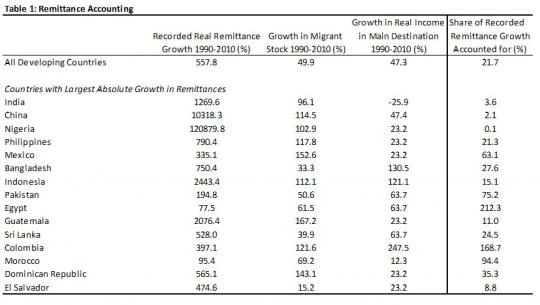

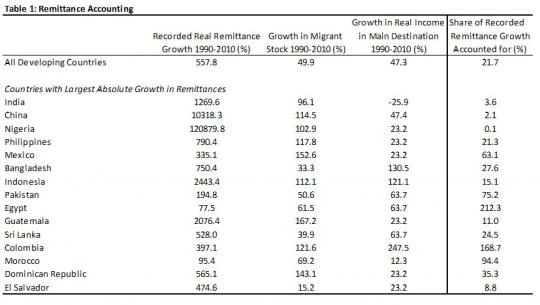

The World Bank, UN, OECD, and a number of researchers have made a concerted effort to use national census data from all around the world to construct bilateral matrices of migration stock. We use UN Population Division data to measure growth in the number of migrants. According to these estimates, there were 123.4 million migrants from developing countries in 1990, growing to 185.0 million in 2010, a 49.9 percent increase. This is shown in the first row of Table 1 below, which shows that this growth in migrant stock is only 9 percent of the recorded growth in remittances over this time period.

Data on the earnings of migrants at a global level over time are not available. We therefore proxy the growth in income earned per migrant with the growth in per capita GDP in the main destination country in which migrants from that country reside (showing in the paper that this appears to be a reasonable assumption based on US data on migrant earnings). We then construct a weighted average income growth rate for all developing country migrants, which we estimate to be 47.3 percent over the 1990–2010 period (column 2 in Table 1). Combining this with the growth in migrant stock, and using the above decomposition, this gives a predicted growth in remittances of 120.7 percent over the 1990–2010 period.

As a result we estimate that only 21.7 percent of recorded remittance growth is due to changes in the fundamental drivers of remittances, with almost 80 percent therefore potentially due to changes in measurement. We do a similar exercise for the 15 countries that have had the largest absolute growth in remittances between 1990 and 2010, and likewise show that for most of them, very little of the growth is accounted for by fundamentals.

If most of the measured growth in remittances at the global level is illusory, resulting from changes in measurement, rather than genuine growth, then we should not expect to see changes in GDP growth coming from it.

Are we now good?

It is frequently claimed that the presence of informal transfers and measurement concerns lead recorded remittances at the macro level to be an undercount of true remittances. The implicit assumption is then that over time we are getting closer to the truth. However, there are also a number of reasons why macro data can overstate remittances, by recording other types of transfers as remittances. For example, the IMF notes that many other types of small transactions such as transfers to family members studying abroad, transfers to travelers undertaking trips, and small trade transactions are often transferred through the same money transfer operators as remittances, and can be difficult to distinguish in the data. Some of these types of transactions are likely to be increasing over time, as the internet facilitates person-to-person trade across borders, and the popularity of study abroad programs grows. Conversations with officials in charge of monitoring remittances also reveal the suspicion that property market booms in some developing countries lead to large surges in measured remittance flows, even though the purpose of these transactions was often for migrants to buy property for themselves. As a result we should not automatically conclude that recorded remittances are necessarily getting closer to the truth in levels over time.

These amounts now greatly exceed the total sum of all aid flows to developing countries, and such big numbers have brought increasing policy attention to the impact of remittances on sending country economies, and various proposals for policy actions to increase the development impacts of remittances. But it has also asked policymakers and some researchers to ask why have such rapid increases in remittances not resulted in noticeable improvements in economic growth in the recipient countries?

In a new working paper with Michael Clemens of the Center for Global Development, we investigate several reasons for the lack of apparent impact of remittances on economic growth. In today’s post I want to focus on one major reason: our claim that growth rates are vastly overstated.

The large overstating of remittance growth

The solid line in the figure below shows macro data on remittances for Mexico. We see steady growth from the mid-1980s to around 2000, then incredibly rapid growth following this. The dotted line shows remittances for Mexico as measured in Mexican household surveys. The micro and macro data track each other very closely in growth rates until 2000/2001, and then diverge from each other, with much faster growth in the macro data in the 2000s.

We find the same pattern in several other countries. So which of these series is correct?

We note first that the divergence in the two series in Mexico occurs at the same time as a law change affecting reporting in the macro data: before 2002 only commercial banks reported their remittance transactions to Mexico’s central bank, but then in 2002 a new regulation required all money transfer companies to register at the central bank and report their remittance transactions on a monthly basis. So suddenly measured macro remittances soar as a result. This suggests that in this case at least, much of the growth in remittances in the macro data is due to changes in measurement. Is this a general phenomenon?

Understanding macro data on remittances

Macro data on remittances come from balance of payments data provided by each country to the IMF. The underlying data that feeds into these aggregates comes from central banks in each individual country. They typically require banks, money transfer operators and other institutions to provide reports on the transactions they process. But this coverage is often partial, and separating remittance transactions from other financial flows can be challenging. As a result, it has long been recognized that macro data on remittances are noisy, but we haven’t seen any previous attempts that attempt to quantify what this means for growth.

We can write:

Global remittances to developing countries = The number of migrants from developing countries*Average earnings per migrant*share of income each migrant remits.

As a result, if we assume that migrants haven’t changed the share of income they remit (an assumption we provide some empirical evidence for in the paper, and also discuss robustness to), then we can write:

Growth in remittances = Growth in migrants + Growth in Migrant earnings + Growth in migrants*Growth in migrant earnings

The World Bank, UN, OECD, and a number of researchers have made a concerted effort to use national census data from all around the world to construct bilateral matrices of migration stock. We use UN Population Division data to measure growth in the number of migrants. According to these estimates, there were 123.4 million migrants from developing countries in 1990, growing to 185.0 million in 2010, a 49.9 percent increase. This is shown in the first row of Table 1 below, which shows that this growth in migrant stock is only 9 percent of the recorded growth in remittances over this time period.

Data on the earnings of migrants at a global level over time are not available. We therefore proxy the growth in income earned per migrant with the growth in per capita GDP in the main destination country in which migrants from that country reside (showing in the paper that this appears to be a reasonable assumption based on US data on migrant earnings). We then construct a weighted average income growth rate for all developing country migrants, which we estimate to be 47.3 percent over the 1990–2010 period (column 2 in Table 1). Combining this with the growth in migrant stock, and using the above decomposition, this gives a predicted growth in remittances of 120.7 percent over the 1990–2010 period.

As a result we estimate that only 21.7 percent of recorded remittance growth is due to changes in the fundamental drivers of remittances, with almost 80 percent therefore potentially due to changes in measurement. We do a similar exercise for the 15 countries that have had the largest absolute growth in remittances between 1990 and 2010, and likewise show that for most of them, very little of the growth is accounted for by fundamentals.

If most of the measured growth in remittances at the global level is illusory, resulting from changes in measurement, rather than genuine growth, then we should not expect to see changes in GDP growth coming from it.

Are we now good?

It is frequently claimed that the presence of informal transfers and measurement concerns lead recorded remittances at the macro level to be an undercount of true remittances. The implicit assumption is then that over time we are getting closer to the truth. However, there are also a number of reasons why macro data can overstate remittances, by recording other types of transfers as remittances. For example, the IMF notes that many other types of small transactions such as transfers to family members studying abroad, transfers to travelers undertaking trips, and small trade transactions are often transferred through the same money transfer operators as remittances, and can be difficult to distinguish in the data. Some of these types of transactions are likely to be increasing over time, as the internet facilitates person-to-person trade across borders, and the popularity of study abroad programs grows. Conversations with officials in charge of monitoring remittances also reveal the suspicion that property market booms in some developing countries lead to large surges in measured remittance flows, even though the purpose of these transactions was often for migrants to buy property for themselves. As a result we should not automatically conclude that recorded remittances are necessarily getting closer to the truth in levels over time.

Join the Conversation