Many people are aware of the concept of a “placebo effect” in medicine and of the idea of a Hawthorne effect – in both cases the concern is that merely being treated can cause the treatment group in an intervention to change their behavior, regardless of what the treatment actually is. Whether or not this is an important question for evaluating the impact of policy depends on the question you are answering – for example, if part of the effect of business training is to cause people to work harder and believe they are better at business, even if the training doesn’t change their knowledge, we might still think business training is an effective policy - what the mechanism is may not matter so much. In other cases of course our interest is in using the intervention to test returns to some specific input or some particular mechanism, in which case we worry a lot more about such effects.

The lesser known cousin of placebo effects and Hawthorne effects is the John Henry effect. This refers to reactive behavior of the control group in an experiment (note it could also occur in a non-experimental evaluation setting). For example, consider an intervention which randomly chooses unemployed individuals to receive extra help to find jobs. A John Henry effect would occur if either the control group decide to prove that they don’t need this help by exerting extra effort in job search than they would have done in the absence of an intervention, or if the control group gets disheartened about not being selected and therefore gives up on job seeking. In either case, a comparison of job outcomes for the treatment and control groups will not yield an unbiased estimate of the effect of the treatment because of this reaction of the control group – with discouragement or extra exertion leading to opposite types of bias.

In American folklore, John Henry was a legendary black railroad steel driver. The owner of the railway company buys a steam-powered hammer to do the job of men, and so in reaction, John Henry (the control) has a competition against the steam drill (the new treatment) – he outperforms the steam drill, but overexerts himself so much that he dies as a result.

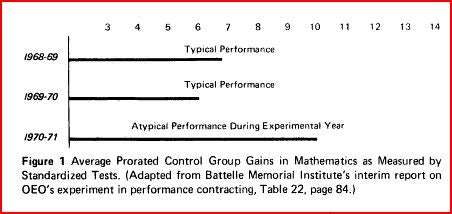

The classic reference to John Henry effects is Saretsky (1972). He comments on an intervention in the U.S. that compared performance contracting in schools to traditional classroom instruction. A comparison of treatment and control schools found no impact on student learning. Saretsky claimed that this could be due to a John Henry effect. For this he gives two pieces of evidence. First, as shown in Figure 1 below, math scores in the control schools were quite a bit higher in the year the experiment took place than in the two previous years. While extra exertion could be one cause, obviously there could be many explanations for this (other reforms taking place in schools, a randomly better cohort, etc.). Secondly, he notes that interviews with project directors gave some qualitative evidence of control group reaction “those teachers were out to show that they could do a better job than those outsiders (performance contractors)”.

Ok, that was 1972. So why am I writing about this now? Two reasons. First, I taught a mini-course on impact evaluation recently in Israel, and was asked whether I knew of any cases where development experiments had found any evidence of a John Henry effect, or whether this was just one of those things people worry about theoretically, but didn’t matter that much in practice. No great examples sprung to mind. Second, there are several recent papers which worry about treatment or control groups responding with effort to treatment status (e.g. Chassang et al, Bulte et al). A new paper that showed up in my Google Scholar recommendations this week is a theory paper by Aldashev et al which worries that “credibility of random assignment procedures might influence people’s perceptions of encouragement and gratitude, if they are assigned into the treatment group, and their feelings of demoralization and resentment, when they are assigned into the control group.”

As evidence for control group demoralization, Aldashev et al cite two U.S. programs. The first was a program for homeless drug users in Alabama, where the control group experience an 11 percent increase in cocaine relapse rates over the experimental period, which they note could be related to demoralization. The second was an employment program in Baltimore, in which young unemployed were randomly chosen to receive tutoring and job search training for one year. The claim is then that some of the control group became discouraged as a result of not being chosen, and stayed on welfare longer.

If these are the best examples one can come up with after 30 years of thinking about the concept, then my contention is that John Henry effects are mostly not a big deal. I think sometimes we think our interventions are a much bigger deal in people’s lives than they really are – in an environment where people are applying for multiple jobs, lots of loans, several government programs, and making numerous other choices that don’t always pan out, the fact that they didn’t happen to get selected for the program we are evaluating may be at most a momentary disappointment in their lives. Of course this argument may not apply to large, high-profile, life-changing interventions – perhaps it matters a lot if you are in a poor rural village with few options that you don’t get selected for the one new program to come along. But only a few of our evaluations fit this category.

Of course the absence of evidence on John Henry effects may just reflect people not paying enough attention to trying to measure this phenomenon – so this is something we should try and do more of. But often our best approach may be to try and reduce the likelihood of such effects in the first place – while it can be hard (or impossible) to hide from the treatment group the fact they are getting a treatment, in many cases the control group need not know they are controls.

Anyone know of a killer example where a John Henry effect really seems important in explaining the results?

Join the Conversation