This is the 23rd in this year’s series of posts by PhD students on the job market.

More than 300 million children currently attend private school. Private markets for education present trade-offs between efficiency and equity: while they offer alternatives to resource-constrained public schools, they come at a price many cannot afford. Vouchers, which subsidize these prices, are perhaps the most common policy to address these concerns.

However, when designing vouchers, policymakers have many options. These include which students are eligible, whether schools can opt-out or charge additional fees, and how payments are made back to schools. Of the five largest voucher programs for primary education, each has a unique design. My job market paper uses new data from India, the world’s largest program, to quantify how these different design choices can shape overall equity and efficiency.

In 2009, India launched what is today the world’s largest voucher system for primary education

India is at the frontier of school privatization. Nearly 50% of K-12 students attend private school, but rates are substantially lower for disadvantaged students. In 2009, the Right to Education Act mandated all private primary schools in the country to participate in a voucher system targeted to these students. Today, this is the largest program in history.

The policy has a unique design. First, eligibility is restricted to students who are lower caste or below the poverty line. Second, it requires all private schools to reserve a quarter of their seats for the program. They cannot charge additional fees or opt-out. Third, for each voucher student, the government pays schools their tuition fees up to a “voucher cap”: the per-child cost in public schools.

To study the policy, I collected new data on the universe of students and schools in Madhya Pradesh, a state with 10 million primary school children and the largest voucher system in India. Students apply for vouchers with a rank-ordered list of private schools, receive one offer through an assignment mechanism, and choose whether to take the offer or enroll in a different school.

Within the assignment mechanism, if a student’s top choice school is oversubscribed, they enter a lottery for its seat. If they win their top choice, students are roughly 40 percentage points (pp) more likely to accept their offer: this serves as a powerful instrument for enrollment in a voucher-offered private school (“voucher takeup”). Using this, I first estimate the Local Average Treatment Effect (LATE) of voucher takeup for more than 100,000 student-level observations. The compliers for this LATE are a selected group of students: those who would have accepted their offer if they received their top choice, but rejected if they received their second or lower choice.

For recipients, vouchers enable greater school choice and reduced tuition payments

I find that vouchers expand the options students can afford. Takeup delivers a modest 12pp increase in private school enrollment, pooled over three years after receipt. This suggests many students would have attended a private school anyway. Nevertheless, the voucher shifts school choices, which may affect students.

Figure 1 shows that vouchers enable access to potentially higher quality schools: takeup increases English instruction by 9pp, GPAs by 0.17SD, and promotion rates by 3.3pp. These magnitudes are sizeable and similar to other voucher studies in related contexts. Beyond quality, voucher takeup reduces distance traveled by 0.36 kilometers and tuition paid by nearly $80 per year – about 6% of household income at the poverty line.

These benefits to recipients may be driven in part by two design choices: (1) schools cannot opt-out, which allows access to high quality schools and amplifies academic gains; and (2) schools cannot charge extra fees, which avoids any tuition payments and amplifies financial gains.

However, other features of the design may affect non-recipients. In particular, schools below the “voucher cap” are paid for each voucher student according to the prices they charge, creating incentives to raise them. For those above the cap, no such incentive exists. I use the roll-out of the policy and a difference-in-differences (DID) design to study its effects on schools, with a particular focus on estimating these effects separately for schools below and above the cap.

Unintended consequences: schools respond to the design by raising prices overall

In 2015 and 2016, the voucher system lowered the minimum age and moved applications online, dramatically increasing applications. Using this variation, I perform a DID analysis that compares schools in markets with greater versus lower exposure, before versus after these policy changes. I measure exposure as the fraction of voucher-eligible students in the market that are already in private school: these students would immediately benefit from applying and so their decision to not apply must be due to application frictions that these policy changes reduce.

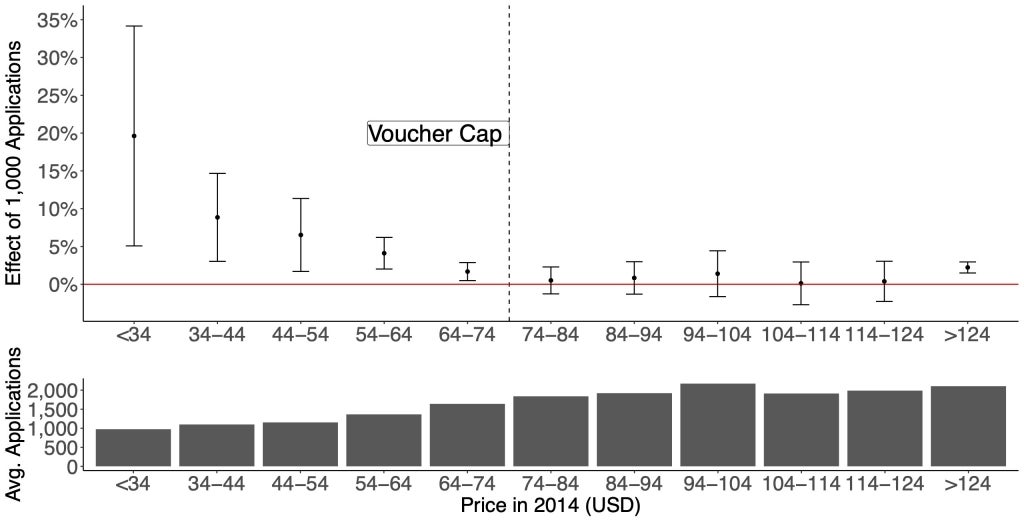

Figure 2 presents the effect of an additional 1,000 voucher applications in a school’s market on its price charged. This is estimated separately for narrow bins of pre-period prices, both below and above the cap. Consistent with their incentives, schools far below the cap substantially raise tuition by roughly 20%, which gradually falls to zero once we reach the cap. These price hikes are consequential, affecting millions of children who do not receive vouchers. In contrast to prices, I find relatively little adjustment in quality measures including teacher-student ratios, GPA value-added, or entry-exit decisions.

In total, the policy delivers a complex patchwork of impacts across the education system driven in part by the policy’s design: potential benefits to recipients via greater choice, but also potential costs to non-recipients via tuition hikes. This raises questions on whether benefits exceed costs, and the extent to which they are driven by design. To assess this, I develop a welfare framework that captures several channels through which voucher design affects student and school decisions.

A model of demand and supply reveals that design choice is critical for equity and efficiency

On the demand-side, students decide whether to apply for vouchers given the chances of winning each offer and potential application costs. Once they receive offers, they decide which school to attend. On the supply-side, private schools strategically set price and quality to maximize profits, with knowledge of how their decisions would affect how students apply for vouchers and enroll in schools. Critically, their incentives to set price and quality depend on the voucher’s design.

One of the model’s key outputs – students’ willingness-to-pay (WTP) for schools – is identified using rich data on (1) high-stakes choices (rank-ordered lists and enrollment decisions) and (2) voucher lotteries, which provide randomization in prices students face. This captures the private value of school enrollment using a revealed-preference approach. Positive externalities from education or limited information about its returns may lead to a larger social WTP. In total, the estimated model allows us to calculate the policy’s dollar-equivalent impact on student welfare, school profits, and government expenditure net of equilibrium responses.

On net, I find that the policy’s total benefits to recipients from vouchers exceed total costs to non-recipients from school adjustment (1.5 to 1), while also reducing measures of segregation by income and caste. While effective, the policy’s payment design substantially reduces its overall efficiency. If we had ignored the strategic responses by private schools, we would have overstated the benefit-cost ratio by a factor of two (2.9 to 1).

Importantly, the framework also allows us to test alternative designs. Switching to a “flat” voucher – which pays all schools a fixed amount – would remove the perverse incentive for schools to raise prices. However, it would also increase voucher payments for schools below the cap. On balance, this design would increase the benefit-cost ratio by 40% (2.1 to 1), suggesting scope for considerable improvement.

Other design elements also have large consequences. Allowing schools to charge “top-up” fees harms voucher students, but cushions profit losses for schools. Allowing schools to opt-out has similar impacts, as high-quality schools exit the program to avoid profit losses. Lastly, switching the assignment mechanism to that of neighboring states (distance-based as opposed to preference-based) results in a misallocation of voucher seats to students. Moreover, because these designs reduce the benefits of receiving vouchers, many students stop applying, which shrinks the program. Overall, they deliver benefit-cost ratios that fall below 1 and diminish reductions in segregation.

These findings illustrate how design choices are critical in determining the ultimate equity and efficiency implications of voucher programs.

Harshil Sahai recently completed his PhD in the Kenneth C. Griffin Department of Economics at The University of Chicago, where he is currently a Postdoctoral Scholar.

Join the Conversation