This is the fifth in this year’s series of posts by PhD students on the job market

In a first-best world, market prices would efficiently allocate goods to buyers whose benefits from using a good are at least as high as the cost of producing that good. Does this imply that charging higher prices screens out potential buyers with lower benefits? Not necessarily. In the real world, potential buyers may face constraints (e.g., limited access to information or credit) that prevent them from buying goods with high expected benefits. It is not clear whether buyers with high benefits are more or less likely to face constraints. If potential buyers who are most constrained have high benefits, then lowering prices through a subsidy could increase take-up and improve allocative efficiency.

In my job market paper, I examine the allocative efficiency impact of lowering prices in an agricultural setting – an area where subsidies are widespread, yet little is known about their allocative efficiency impact. I use a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to test whether lower prices differentially allocate an improved wheat seed to farmers with higher or lower returns. The study was implemented in Bangladesh, the fifth largest wheat importer in the world. The improved seed variety, BARI Gom 33, was first introduced in 2017 to help restore wheat cultivation through its resistance to major crop diseases such as wheat blast.

Experimental Design

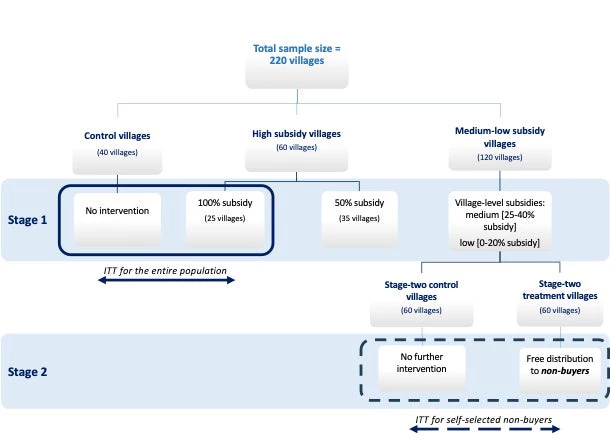

Figure 1 summarizes the two-stage experimental design. In the first stage, I randomly allocate 220 villages to either a pure control arm or a treatment arm in which the subsidy rate for the new seed is randomized at the village level. I divide the subsidy levels into three categories: high (50 or 100%), medium (25, 30, or 40%), and low (0, 10, or 20%) subsidy. The subsidy rate is with reference to the official price of 40 BDT/kg. Each treated farmer is offered one seed package in a take-it-or-leave-it design. The size of the seed package is 15 kg, which is sufficient for an average plot of 0.3 acres as per the recommended seeding rate. The official price of the seed package is 600 BDT, whereas the average daily wage in the sample is 500 BDT.

In the second stage of the experiment, I randomly allocate villages in the medium- and low-subsidy categories into stage-two treatment and stage-two control. In stage-two treatment villages, farmers who did not buy the seeds in stage one are offered the same seed package for free before planting. Stage-two control villages, on the other hand, do not receive any further intervention after receiving stage one treatment. That is, stage-two treatment randomizes free distribution across non-buyers from stage one.

Figure 1: Experimental Design

The two stages of the experiment were implemented in one agricultural season before planting. The timing of the intervention is critical for two reasons. First, seed distribution had to take place before the planting season to be relevant for farmers’ seed choice decisions. Second, at the time of the seed distribution many farmers had not sold the harvest from the preceding season (Monsoon) yet. Hence, farmers facing credit or liquidity constraints may be sensitive to small changes in seed prices.

The two-stage experimental design allows me to compare the outcomes of non-buyers with the outcomes of the farmers who receive the seeds for free at random. The randomization of free distribution in stage one allows me to estimate treatment effects over the entire population. The randomization of free distribution in stage two allows me to estimate treatment effects among the farmers who choose not to buy the seed at stage one. Using these estimates, I examine whether the realized returns of the farmers who decline to buy the seeds are different from the realized returns of the average farmer.

Results on Usage

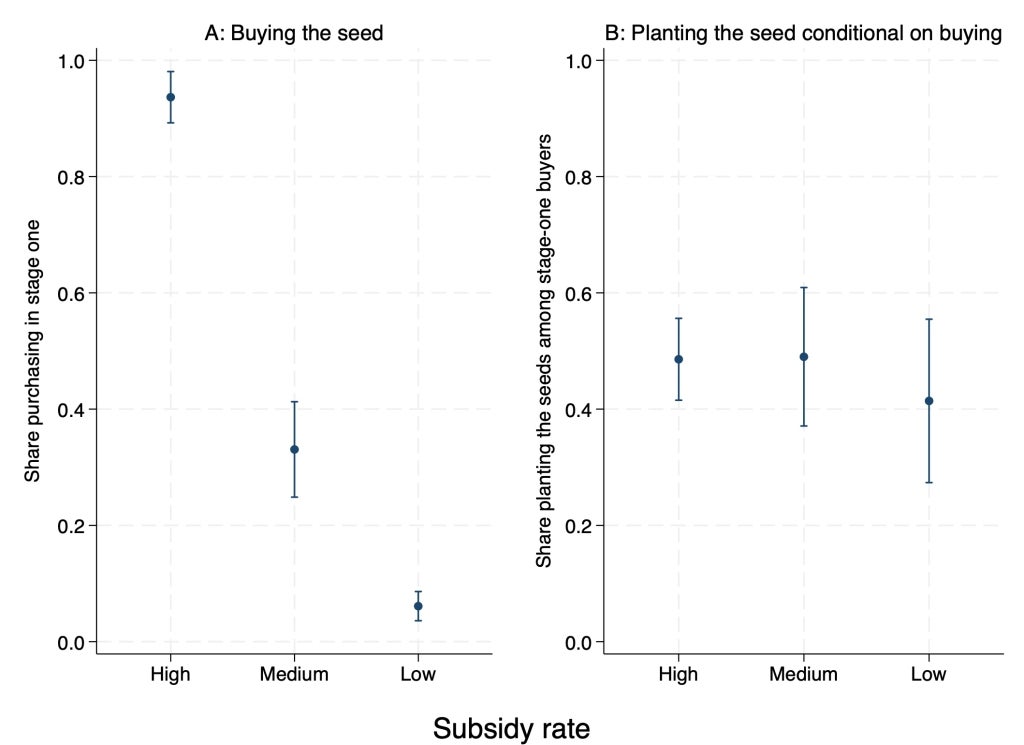

The first stage of the experiment shows that farmers are highly responsive to the change in prices, particularly in the subsidy range of 50% to 0%. As shown in Panel A of Figure 2, moving from a high to a low subsidy level decreases demand from 94% to 6%. The immediate question is whether farmers who do not buy the seed do so because they expect low returns to adoption or because some constraints (e.g., uninsured risk, or credit limitations) prevent them from buying the seed. The results on actual adoption among seed buyers, presented in Panel B of Figure 2, suggest that the subsidy does not sort farmers based on their likelihood of planting the seeds. The likelihood of planting the seeds is similar across farmers who took up the seeds at different subsidy levels.

Figure 2: Demand vs Usage of Seeds

The second stage of the experiment shows that farmers who decline to buy the seeds in stage one end up planting the seed (rather than eating it or passing it to other farmers) and increasing their wheat cultivation when offered the seed for free. Stage-two free distribution to non-buyers causes a net increase in adoption of 32 percentage points, compared to a 41-percentage point increase in adoption in stage-one free-distribution villages. The difference between these point estimates is only marginally significant. Not only do farmers use the distributed seeds to replace existing wheat seeds, but they also change their cropping pattern and increase wheat cultivation at the extensive and intensive margins. The treatment effect of stage-two free distribution on wheat cultivation by non-buyers (21 percentage point increase) is on par with the treatment effect of stage-one free-distribution on wheat cultivation by the average farmer (28 percentage-point increase). The similarity in treatment effects on adoption between non-buyers and the average farmer persists one year after the intervention. These findings suggest that going from a high to a medium-low subsidy level prevents farmers who are willing to adopt the new seed -- or almost as willing to adopt as the average farmer in the population -- from buying.

Results on Returns

A comparison between the returns of the average farmer and the returns of non-buyers does not suggest that non-buyers select out of buying the seed due to lower returns. For both stage-one and stage-two free distribution, the treatment effects on plot profits are not positive. This can be explained by the finding that the new seed replaced not only inferior wheat seeds, but also other crops that are more lucrative than wheat. Yet, importantly, the profits of self-selected non-buyers are similar to those of the farmers in stage-one free-distribution villages. Although the results on profits are noisy, I can rule out that the returns of self-selected non-buyers are lower than the returns of the average farmer by 30%.

The two-stage randomization allows me to infer the returns of the farmers who are induced to buy the seed as the subsidy level increases from low to medium (i.e., would-be buyers at the medium subsidy). I show that the would-be buyers at the medium subsidy level have higher than average returns. Specifically, the inferred value of expected profits among would-be buyers at the medium subsidy is 50,000 BDT/acre, whereas the average profit in the stage-one free-distribution villages was 40,000 BDT/acre. Thus, lowering agricultural input prices in the study setting does not distort allocation to lower return farmers.

A Potential Mechanism

Several mechanisms may explain why non-buyers select out of buying the improved seed if their actual returns are not lower than the returns of the average farmer. While I cannot isolate one mechanism as an exclusive explanation for the main results, I do provide suggestive evidence that binding credit constraints may provide a plausible explanation for non-buyers' outcomes. Empirically, I find that non-buyers who are most responsive to stage-two free distribution treatment are more likely to report binding credit constraints at baseline compared to the least affected non-buyers. Theoretically, the credit constraints mechanism is consistent with a model in which farmers' willingness-to-pay (WTP) for agricultural inputs is shifted downward when the credit constraint binds. That is, a binding credit constraint can result in a gap between revealed WTP and expected returns.

Policy Implications and Further Research

In conclusion, this paper provides the first experimental evidence that agricultural input prices do not screen farmers based on their returns – despite there being substantial heterogeneity in returns across the sample. This implies that policy makers aiming to increase the dissemination of agricultural technologies cannot rely on market prices as a mechanism for targeting high return farmers. Nevertheless, this finding does not imply that a universal subsidy is an optimal policy solution either. An alternative policy might be to use a targeting mechanism independent of prices. For example, the second wave of agricultural input subsidies in Sub-Saharan Africa relies on agricultural extension agents to target farmers with high expected returns. This policy might be justified when prices fail to sort farmers based on their returns. However, relying on the subjective judgment of extension agents entails its own problems. Further research is needed to evaluate new mechanisms for targeting farmers with high returns to adoption of modern agricultural technologies.

Mai Mahmoud is a PhD candidate at Tufts University.

Join the Conversation