This is the eighth in this year’s series of posts by PhD students on the job market

Development economies are characterized by poor transportation infrastructure and the prevalence of distortions caused by the informal economy. In Mexico City, it takes a typical low-skilled worker approximately two to three hours to commute to jobs in the center of the city.

On the other hand, labor market informality is one of the most significant sources of distortions in low- and middle-income countries, with important implications for aggregate efficiency. Within developing countries, 50 to 60 percent of total employment is informal. Establishments that are less productive than formal firms and avoid labor market regulations (i.e., taxes or social security contributions). As a consequence, the informal sector creates labor wedges across firms that cause factor misallocation, which ultimately lowers aggregate total factor productivity (TFP) (Banerjee and Duflo, 2005; Restuccia and Rogerson, 2008; Hsieh and Klenow, 2009).

In my JMP, I explore the link between transit improvements, informality, and aggregate efficiency at the city level. I test whether infrastructure projects that facilitate transit within a city improve allocative efficiency by reallocating workers from the informal to the formal economy. As a result, aggregate gains from these projects can be larger relative to standard urban models that assume perfectly efficient economies. The core intuition is that in cities in developing countries, workers in remote locations prefer to work in low-paid informal jobs near their residence rather than incurring in high commuting costs to access formal employment. Transit developments may provide better access to formal jobs, leading to an expansion of the formal sector and improving labor allocation across firms.

Case study: Mexico City

I analyze this question in the context of Mexico City, which constitutes a relevant and informative case study for several reasons. First, it has a dense concentration of economic activity, accounting for around 8.9 million people and involving the transport of millions of workers every day. Second, the Mexican case is typical for developing countries, especially in Latin America, where more than 50% of the urban labor force and 70% of economic establishments are informal. Furthermore, the city constructed a new primary subway line (Line B) in the early 2000s, connecting remote areas in the north-east with the center of the city. This line was planned several years earlier, suggesting that the opening dates were uncorrelated with local demand and supply shocks that can bias my estimates. Moreover, Mexico City collects unique data at a highly granular level that allows me to observe the precise location of formal/informal jobs and workers across census tracts in the city.

Three empirical facts

In the first part of the paper, I document three empirical facts that suggest a negative relationship between the accessibility of jobs and informality.

- Informal workers are more sensitive to commuting costs than their formal counterparts: I exploit cross-sectional variation among informal vs. formal workers to show that informal workers spend less time commuting, make fewer trips, and work closer to home relative to their formal counterparts. For instance, informal workers spend 40% less time commuting and are 10 percentage points more likely to work in the same municipality in which they reside. This implies that informal workers are more sensitive to commuting costs than their formal counterparts, indicating that the commuting elasticity in the informal sector is higher.

- High commuting costs induce workers in the outskirts of the city to choose working in an informal business: I compare the location of informal and formal workers. I document that formal jobs concentrate in the middle-west and center of the city, where most economic activity takes place. By contrast, most informal workers reside in the east and on the periphery of the city. This fact suggests that high commuting costs induce workers in the outskirts to choose working in an informal business rather than working in a formal job in central locations.

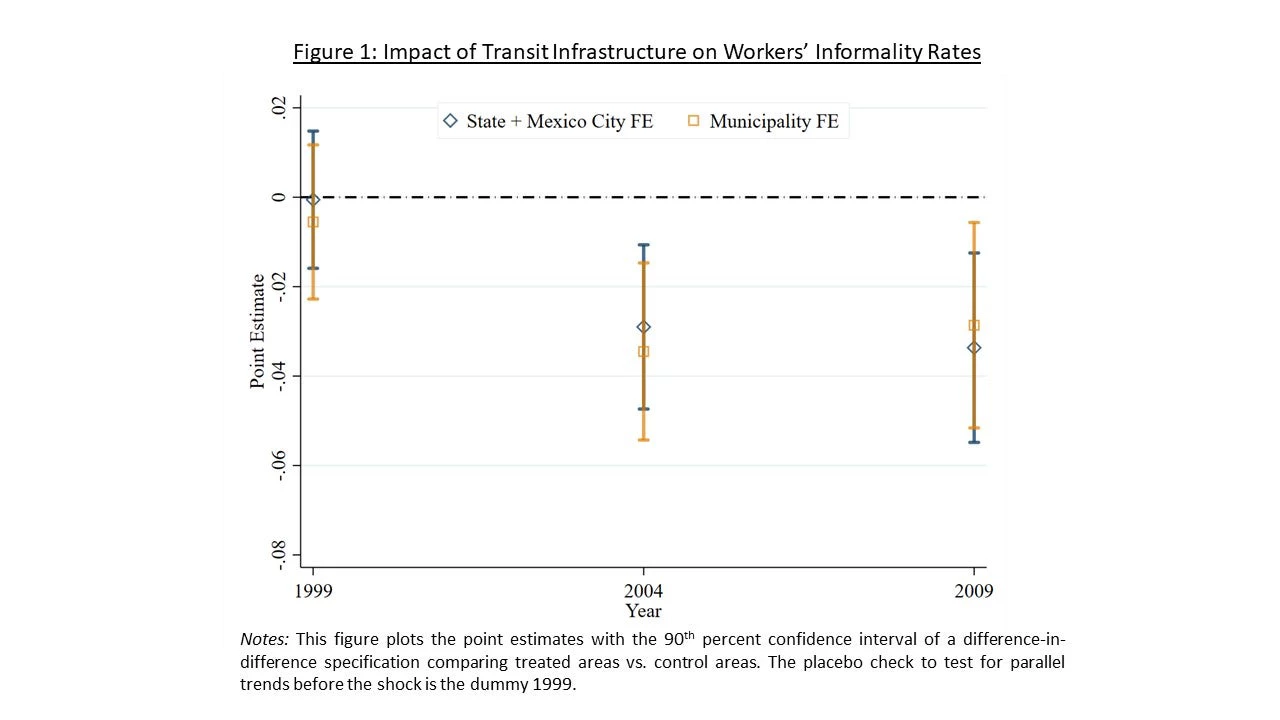

- Transit infrastructure lowers informality rates in treated areas: I exploit the construction of a new subway line that connected remote locations with the center of Mexico City as a transit shock to provide causal evidence that transit infrastructure leads to a decrease of informality rates. Specifically, I estimate a series of difference-in-differences specifications that use variation in access to new transit as identifying variation. The main finding is that informality rates decrease in locations close to the new stations. Figure 1 shows the results of my preferred specification. Workers’ informality rates drop by 2 to 4 percentage points after the construction of the new line. Similarly, the ratio of formal to informal residents increased by 7% in areas nearby to the new stations. I corroborate the exogeneity of the line by documenting no apparent pre-trends in the preceding periods.

Quantifying the welfare effects of transit infrastructure

I rationalize the empirical results through the lens of a quantitative spatial equilibrium model of the city. To this end, I extend recent work (Ahlfeldt et al., 2015; Allen et al., 2019; Tsivanidis, 2019) that assumes perfectly efficient economies by adding distortions and factor misallocation to an urban quantitative framework. From a first-order approximation and following recent work from the Macro-development literature, I provide a formula that decomposes the welfare gains from transit developments in urban models into a “direct” effect and an allocative efficiency term (Baqaee and Farhi, 2019). Intuitively, firms that face larger wedges are too small relative to the efficient allocation. Then, if a trade or commuting shock reallocates workers to firms that are too “small”, the welfare gains from these shocks are larger relative to an economy under perfect competition.

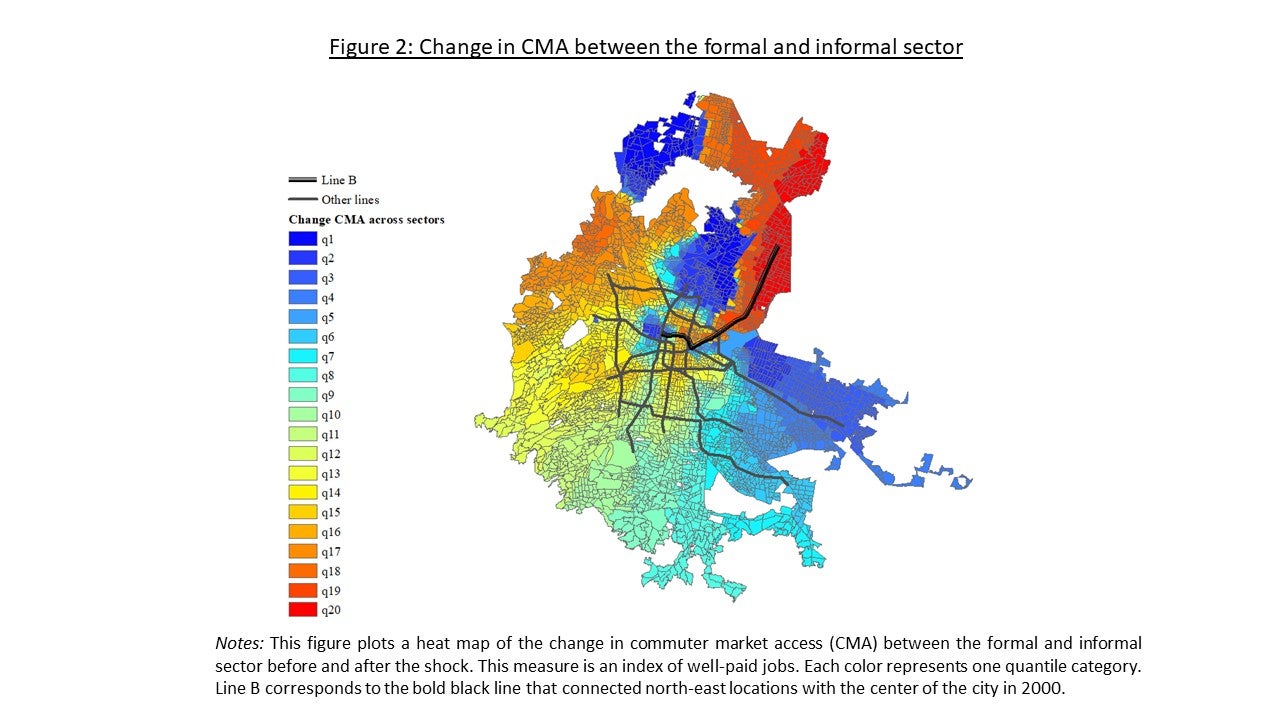

The key parameter to estimate is the labor supply elasticity across sectors, which governs the reallocation from the informal to the formal economy. I build commuter market access (CMA) measures for both the formal and informal sectors following Tsivanidis (2019). Figure 2 shows the change in CMA measures between the formal and informal sectors before and after the shock. Consistent with the reduced-form evidence, I show that locations close to the new subway line experienced better access to formal employment relative to informal jobs. As a result, the transit shock induced workers to reallocate from the informal to the formal economy. This effect implies that line B generated additional welfare gains through an allocation margin that models under perfect competition fail to capture.

The primary goal of the model is to quantify the welfare effect of the new line. The results suggest that line B of the subway increased welfare by 1.3 percent. I find that the direct effects under perfectly efficient economies explain approximately 87% of the total gains, while the reallocation of workers from informal to formal firms explains the remaining 13%.

What can we say to policy-makers?

-

In terms of the cost-benefit analysis, the reallocation of workers from the informal to the formal sector increases net welfare by 15%. Line B generated a net gain of USD 1.85 per dollar spent on the new infrastructure. This effect would have been only USD 1.60 under the assumption of a perfectly efficient economy.

-

My findings imply that governments in developing countries need to depart from the classic approach of transportation demand to answer the question of where to allocate future infrastructure. For instance, authorities need to prioritize projects that connect poor areas with efficient locations as it can generate more gains than connecting locations with a similar composition of workers.

Román David Zárate is PhD candidate in the Economics Department at the University of California, Berkeley.

Join the Conversation