At least US$1 billion is spent annually training at least 4 to 5 million potential and existing entrepreneurs in developing countries. Last year I blogged about a review paper I wrote (now out in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy) which contained a meta-analysis of the impacts of training on firm profits and sales estimated in different RCTs. This found that training has a significant positive average effect on both profits and sales, with an estimated 4.7% improvement in sales and 10.1% improvement in profits.

Normally this would then be job done – you write and publish the paper, and move onto something else. But as I was writing that paper, I was also asked to edit with Chris Woodruff and a great group of co-editors the first of VoxDev’s new dynamic literature reviews (or VoxDevLits), on training entrepreneurs. We released the first version in December 2020, which contained the above estimates. I was asked by several policy organizations to present what we know about training based on these two reviews, and in turn got to hear what questions policymakers and practitioners had that our reviews had not provided evidence on.

Business training and job creation

One of the most frequent questions was “What is the impact of business training on job creation?”. Employment is an important concern for most policymakers, and government subsidies for training are sometimes motivated, in part, by the belief that it will not only help the person being trained, but also help create jobs for others. The advantage of the dynamic literature review was that we could revise it and see what the literature has to say on this question. We have just released version 2, which now includes a new meta-analysis of the impacts of business training programs on employment.

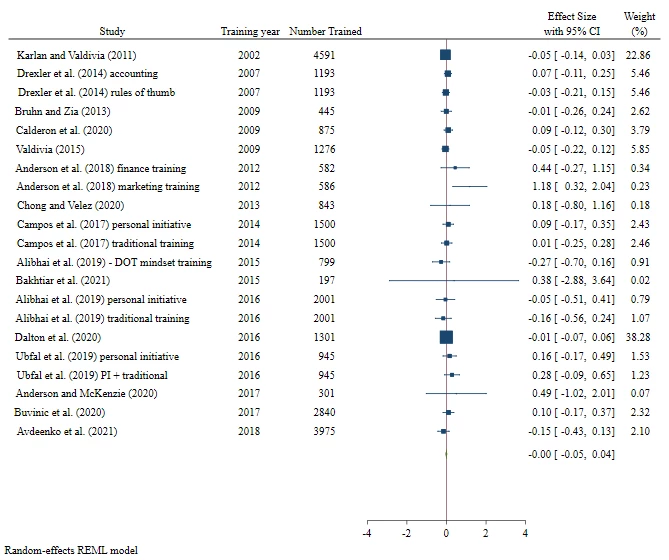

Figure 1 shows the estimated effect size on employment and associated 95 confidence interval from each business training experiment. The outcome is the number of workers, so that e.g. a -0.05 point estimate would be a reduction of 0.05 of a worker. We see that the estimated impacts are small and not statistically significant in almost every study, and the meta-analysis finds an average effect of 0 workers, with a 95 percent confidence interval of (-0.05, +0.04) workers per trained firm. That is, the typical business training that has been evaluated has not created any additional employment. This is true of both traditional business training programs, as well as some of the alternatives to traditional training such as rules of thumb and personal initiative training programs that have improved sales and profits by more in some cases.

Figure 1: Estimates of the Impact of Business Training on Employment

Why isn’t training more successful at creating jobs, and is there still hope for job creation?

The typical microenterprise taking part in business training has either none or only one additional worker apart from the owner. The average impacts on business profits is 12.1% (the new version updates the meta-analysis on profits and sales to include several new studies as well). This equates to only an additional US$5-10 a month for a firm earning US$50-100 a month in profit. This level of growth is likely to be possible with the existing labor, and it is unlikely to be sufficient to support the firm taking on another employee in most cases. When a firm has zero or only one paid worker, adding a worker can be a big step (doubling labor inputs after all), and the gains from training may not be enough to take this step.

This suggests policymakers should be cautious about justifying such programs on the basis of a lot of job creation. However, here are some caveats to note:

· Most of these evaluations only look at impacts over 1 to 2 years after training. If some of the trained firms are able to slowly reinvest their additional profits and grow over time, then business growth may be higher over longer time horizons and it is possible that employees could be added at a later stage.

· There may be still some job creation impact in terms of i) training helping people to start businesses that would not otherwise get started (most of the studies in the literature review focus on training existing entrepreneurs); and ii) helping existing businesses survive for longer (which again typically will show up over longer time horizons). Moreover, as well as providing a job for the entrepreneur, it may also provide some work for other family members, and this unpaid family labor is not always counted as employment – some studies look at total employment whereas others focus on paid employment.

Nevertheless, if the goal is to create jobs for others, the focus may need to be on larger firms. Consulting programs with SMEs have shown some promise in this regard. For example, in this forthcoming ReStud paper, my co-authors and I found group-based consulting in Colombia with firms of average size 58 employees resulted in a 6 to 15 worker increase in employment over the next 3 to 4 years relative to the control group (see this post for a summary). Likewise, Bruhn et al. (2018) found that local consultants working with firms of an average of 14 workers in Mexico grew by 5.7 formal employees relative to the control group over the next five years. So moving beyond the very micro firms towards at least small firms seems useful if the focus is on employment.

What else is new in version 2?

A nice feature of the VoxDevLit updates is that the major new content is shown in green, so if you have read the first version, you can skim through and see what is new in the update. Another area that we received questions from policymakers about was doing training and consulting for specific groups. Two that we now discuss are studies in fragile and conflict afflicted states (including RCTs in Venezuela and Yemen), and programs to help youth start new businesses. We also include more discussion of the role of market-based solutions in expanding access to training. The fact that the updated reference list contains about 20 new references shows how active a research area this is, and makes me excited to see what we will learn by time it comes to version 3.

Join the Conversation