This post was co-authored by Sacha Dray, Felipe Dunsch, and Marcus Holmlund.

Impact evaluation needs data, and often research teams collect this from scratch. Raw data fresh from the field is a bit like dirty laundry: it needs cleaning. Some stains are unavoidable – we all spill wine/sauce/coffee on ourselves from time to time, which is mildly frustrating but easily discarded as a fact of life, a random occurrence. But as these occurrences become regular we might begin to ask ourselves whether something is systematically wrong.

So it is with survey data, which is produced by humans and will contain errors. As long as these are randomly distributed, we usually need not be overly concerned. When such errors become systematic, however, we have a problem.

Data for field experiments can be collected either through traditional paper-based interviews (PAPI, for paper assisted personal interviewing, not for this) or using electronic devices such as tablets, phones and computers (CAPI, for computer assisted personal interviewing). There are some settings where CAPI may not be appropriate, but it seems safe to say that CAPI has emerged as a new industry standard. Even so, we sometimes encounter resistance to this no-longer-so-new way of doing things.

The next time you are planning a survey and your partners consider CAPI impractical or inferior to PAPI, refer to the following cheat list of some of the advantages of

electronic data collection. These are based on some of the things we have found to be most useful in various surveys carried out as part of DIME impact evaluations.

1. Avoid mistakes before they happen. Did you hear the one about the 6-year-old with two children who was also his own grandmother? With a long and complex paper questionnaire, such errors can easily occur. CAPI allows us to build in constraints to, for example, create automatic skip patterns or restrict the range of possible responses.

2. Ask the right questions. As part of an experiment to test the effectiveness of different forms of incentives on midwife attrition in Nigeria, we used our survey to check whether midwives received the type of incentive they were assigned to. Here, enumerator error could lead to contamination of the experiment by informing the interviewee of different forms of incentives potentially received by their peers, and so it was vital that exactly the right questions be asked for each midwife. To ensure this, the question was automatically filtered depending on answers to a set of simple questions early in the questionnaire, each of them with their own restrictions. This level of assurance cannot be achieved with a paper survey.

3. Change your mind. Despite our best efforts including extensive piloting, we sometimes ask questions in the wrong way. In a recent survey of Nigerian health workers, we soon learned that what we were calling a “uniform” is more commonly considered a “cover” or “coverall”. We were able to correct this early in the survey and to include a picture of what we meant directly in the questionnaire just to be sure, all without the logistics of re-printing or distributing paper questionnaires.

4. Get better answers. Getting reliable information about socially undesirable attitudes or behaviors is difficult. In Honduras, we are testing an employment readiness and labor market insertion program for at-risk youth and are interested in participation in violence and criminality, among other things. These are difficult questions to ask directly, but using a tablet allows us to easily isolate this set of questions for self-administration without worrying about having to recompile separate sheets for respondents later on. Also, this provides better protection for respondents, as their answers to these and other questions are not easily accessible to outsiders. And, where we are concerned with framing (i.e., where the order of questions might affect the responses), with a tablet we can easily randomize the order of questions. On paper, this is difficult and becomes increasingly complex as the number of questions to randomize increases. Finally, there are some things that are best captured not by asking questions but by observing, and here we may build simple games or tasks into the tablet and directly record behavior.

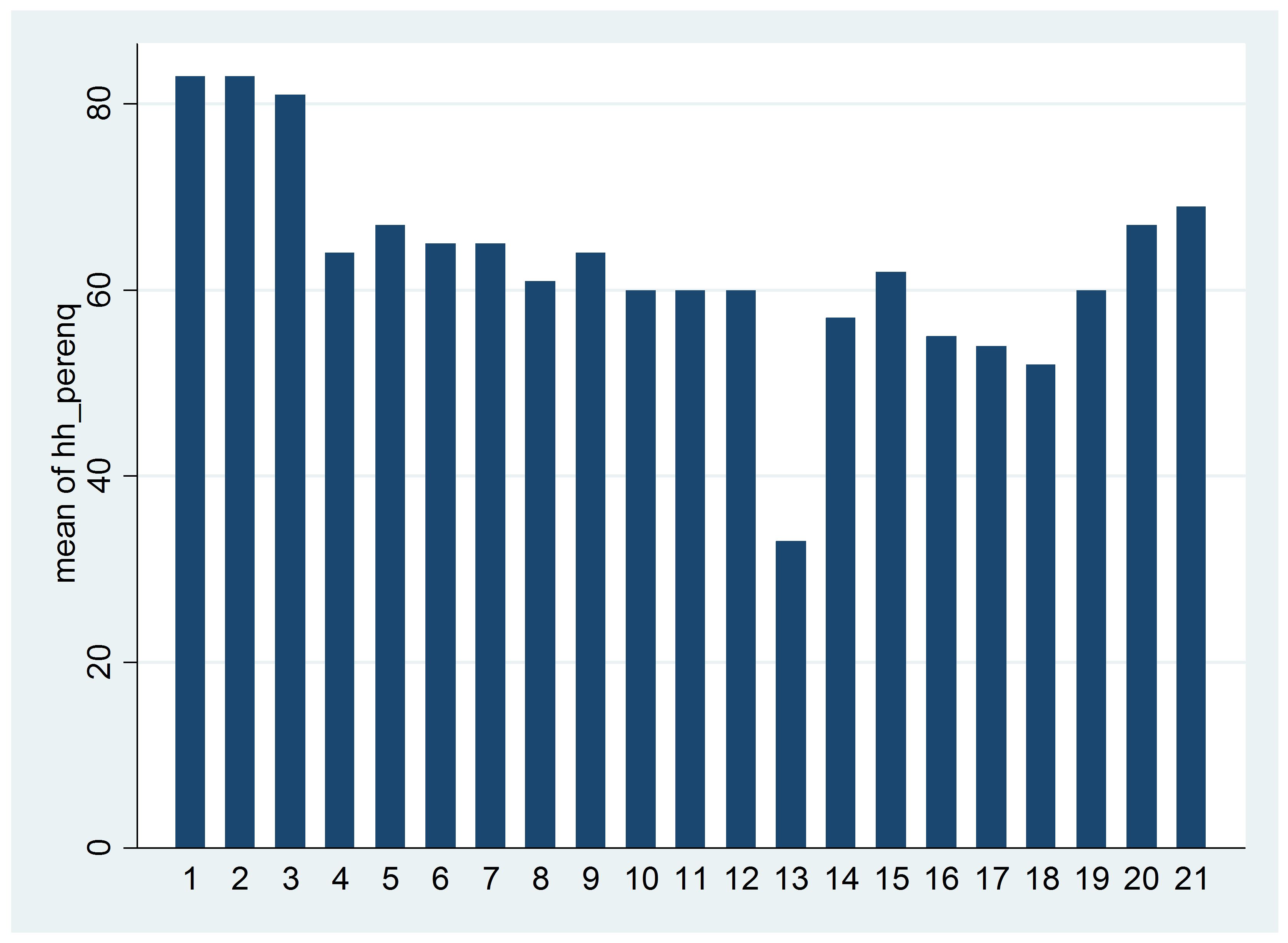

5. Know how work is progressing. The graph below shows the number of surveys (y-axis) completed by each enumerator (x-axis) for a survey on a flood risk prevention intervention in Senegal. Team 1 (enumerators 1-3) stands out for being relatively more “productive”, but that outlier status triggered further analysis of their data, revealing several anomalies: ultimately it was agreed that the team’s work would be repeated from scratch. A similar analysis could have been done with paper-based surveys, but this would rely on accurate reporting by the survey firm which may not have the incentive to tell the full truth about situations like the one below (the graph shows completed interviews uploaded to the server, a more objective metric). It also would have taken longer.

6. Eliminate data entry error. Data collected on paper forms eventually needs to be digitized. While this process can be done concurrently with data collection, it is another source of error, both because of the potential for errors in the data entry program itself and by those persons responsible for entering data. We have not directly compared the quality of raw data collected through CAPI vs. PAPI, however, but perhaps someone else has?

7. Experimentally test survey design: CAPI makes it much easier to run survey experiments, for example randomizing the order or framing of questions to see whether this has an effect on the answers received. We did this for a survey in Nigeria to measure the effect of framing statements on satisfaction with the conditions at primary healthcare facilities positively or negatively. We find that patients report extremely high satisfaction with positively framed statements – above 90% for 8 of 11 statements (e.g. The staff at this facility is courteous and respectful). However, this satisfaction drops significantly – by between 2 and 22 percent, depending on the statement – when the same statements are posed with negative framing (e.g. The staff at this facility is rude and disrespectful).

There are, of course, other important advantages of electronic data collection, such as shorter survey times (as documented in Caeyers, Chalmers, and De Weerdt 2010), reduced waste and clutter, and an easier life for enumerators (less to carry, less to pay attention to during interviews). That said, you do need tablets or smartphones (though these can be reused in other surveys), there is a bit of a learning curve in programming the first questionnaires, and there is always the potential that technical glitches can lead to data loss. But such issues are outweighed by the considerable advantages that electronic data collection yields in terms of data quality.

What are your experiences with electronic vs. paper surveys? Any must-dos or don’ts?

For more on this topic:

- “A Comparison of CAPI and PAPI through a Randomized Field Experiment” by Bet Caeyers, Neil Chalmers, and Joachim De Weerdt

- “Paper vs. Plastic Part I: The survey revolution is in progress” and “Paper or Plastic? Part II: Approaching the survey revolution with caution” where Markus Goldstein, Raka Banerjee, and Talip Kilic beat us to the punch by nearly four years

- “Electronic vs. Paper-Based Data Collection” post by former former DIME Field Coordinator Cindy Sobiesky on the SurveyCTO blog

- “Going Digital: Using digital technology to conduct Oxfam’s Effeciveness Reviews” by Emily Tomkys and Simone Lombardini

Join the Conversation