This is the eleventh in our series of posts by students on the job market this year.

Evidence suggests that ethnic diversity can lower firm output due to poor social ties and taste-based discrimination among workers (Hjort, 2014; Afridi et. al., 2020). In my job market paper, I designed a field experiment to test whether such effects depend on the type of production technology in use and whether they can be mitigated through repeated intergroup contact. I focus on the effects of technology because it might affect the way workers interact during production -- it could influence the type of contact and by determining complementarities in worker efforts (labor inputs), it could affect the incentives to collaborate or interact.

I partnered with a processed food manufacturing plant in West Bengal, India that employs both Hindus and Muslims — the two main religious groups who have a long-standing history of conflict in India (Pillalamari, 2019).

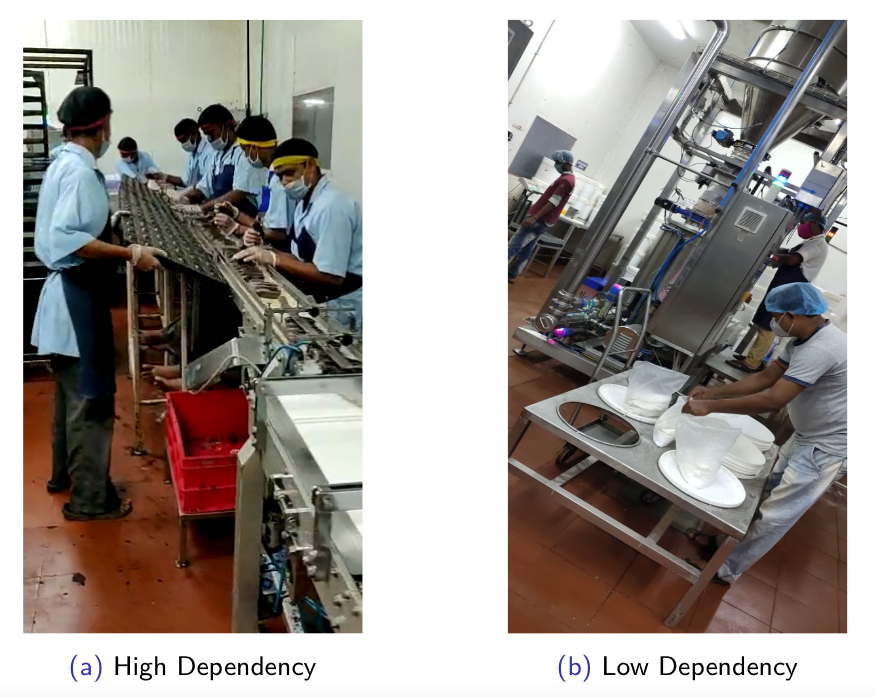

Production tasks at the factory can be categorized as High-Dependency (HD) or Low-Dependency (LD) based on the degree of continuous coordination required amongst workers to ensure uninterrupted production, and the dependence on co-workers for breaks. I randomly assigned approximately 600 workers to religiously mixed or Hindu-only teams (these two types of teams are formed naturally at baseline due to the distribution of Hindus and Muslims in the population — 80% Hindu and 20% Muslim) and kept them intact for a period of four months to estimate both static and dynamic effects of mixing in HD and LD tasks.

Figure 1: High- (HD) and Low-Dependency (LD) Tasks

Experimental Design and Data

There are multiple production lines at the factory, each of which comprises a series of HD and LD tasks which need to be completed to produce the final product. I designed the experiment to estimate the effects of religious mixing on line-level output as well as on individual task-level performance. The randomization was designed to form two distinct types of teams at the line-level:

1. HD-mixed line — production lines with religiously mixed teams only in HD tasks and

2. LD-mixed line — production lines with religiously mixed teams only in LD tasks.

As a result, at the task-level, I have the following four types of teams: 1. HD-mixed 2. HD non-mixed 3. LD-mixed and 4. LD non-mixed

Key Results

The experiment uncovers three key findings.

Result 1: Religious mixing leads to lower team output, but only in HD-tasks

I find that HD-mixed lines produce 5% lower output than LD-mixed lines over the period of the intervention. Analyzing performance at the individual level indicates that while mixing leads to lower performance in HD tasks, it does not affect productivity LD tasks. Therefore, the overall line-level differences in output can be explained entirely by differences in HD tasks.

Result 2: Treatment effects of mixing in HD tasks attenuate completely in 4 months

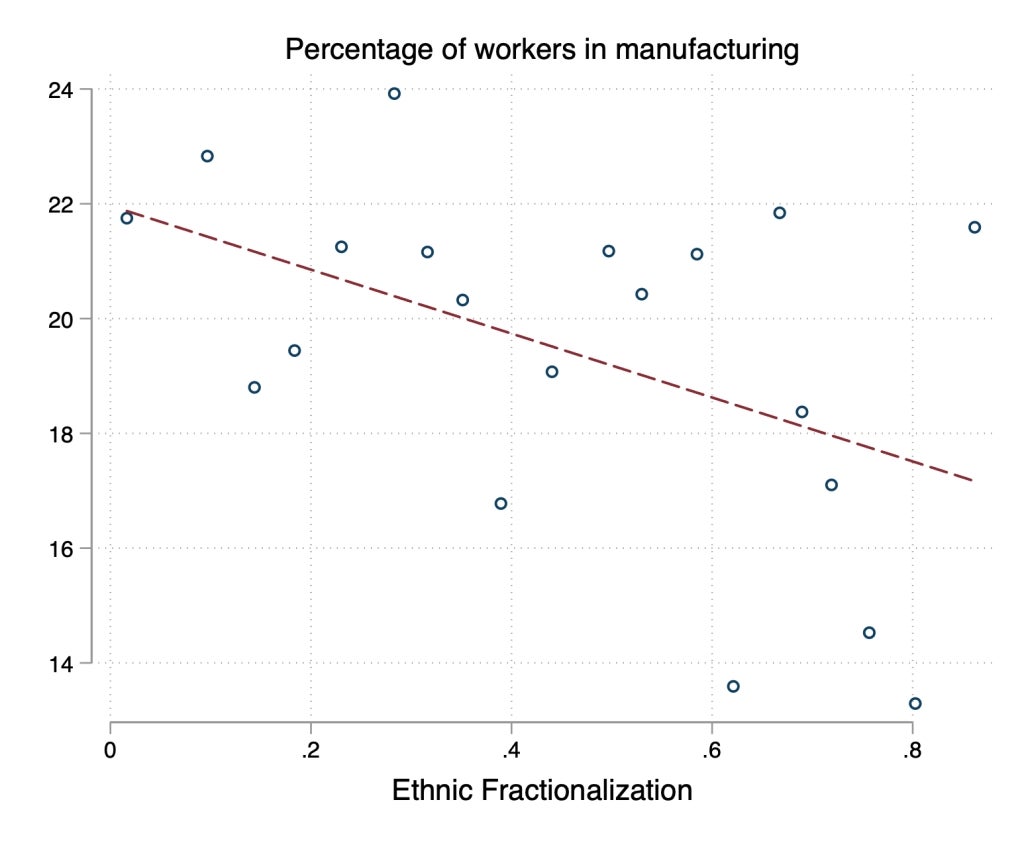

Figure 2: Treatment Effect on Line-Level Output (Event-Study)

Figure 2 shows the difference in output across different lines over time. The largest difference in output between HD-mixed and LD-mixed lines occurred at the beginning of the experiment and it attenuated over time, subsiding completely by the end of the experiment. From the task-level analysis, I find that this is driven entirely by output gains in HD-mixed teams.

Result 3: Attitudes improved in HD-Mixed teams, but not in LD-Mixed teams

The third key finding of this experiment is that at endline, there is a reduction in negative out-group attitudes (such as willingness to take orders from Muslims, comfortable communicating with Muslims etc.) for Hindu workers which is substantially (23%-56%) larger from mixing in HD teams compared to LD teams. This is despite the fact that HD-mixed teams suffered negative output shocks, while LD-mixed teams did not.

Summary of Results:

The largest positive effects of treatment on attitudes occurred in teams that also suffered the largest initial negative output shocks. This suggests that working in close quarters even with some frictions (in HD teams) leads to more positive effects on intergroup relations than working in LD teams. In other words, technology that incentivizes individuals to learn to work together is important in overcoming existing intergroup differences -- and leads to improved relations and team performance. However, the tension between the goal of maximizing short-run productivity and that of improving inter-group relations might mean that we only see integration where it doesn’t matter for productivity. This could limit the chance for people to learn to work together with better outcomes for social attitudes.

Policy Implications

The policy implications of my findings hinge crucially on whether firms are aware of the costs of religious diversity and how they depend on the production function. To explore this, I surveyed more than one hundred production supervisors across five different firms. The findings from the survey suggest that there is some understanding of the effects — between 30%-50% of respondents correctly predicted the results of the experiment. But crucially, 90% of them said that they are unwilling to segregate workers by religion despite the possibility of losses. While a fair share (25%) cited negative effects of mixing dissipating over time as their reason for this, the first-order concern was about such segregation making work culture vulnerable to external political tensions.

These findings suggest that effective policy design in this context must look beyond just the direct effects of diversity on production. They further advocate HR policies (such as keeping workers together for sufficiently long periods) that trade-off short run costs for long-run benefits of integration. To ensure that this is sustainable, government (short-term) subsidies for firms (especially for those with HD production) that are willing to take such steps might be beneficial as well.

Future Research

A deeper analysis of the role that technology plays in determining the effects of diversity can help us understand how the costs of diversity might change as economies undergo structural transformation. My results suggests that ethnic diversity is likely to be more costly in the manufacturing sector (relative to agriculture or services) because of the larger concentration of high-dependency jobs.

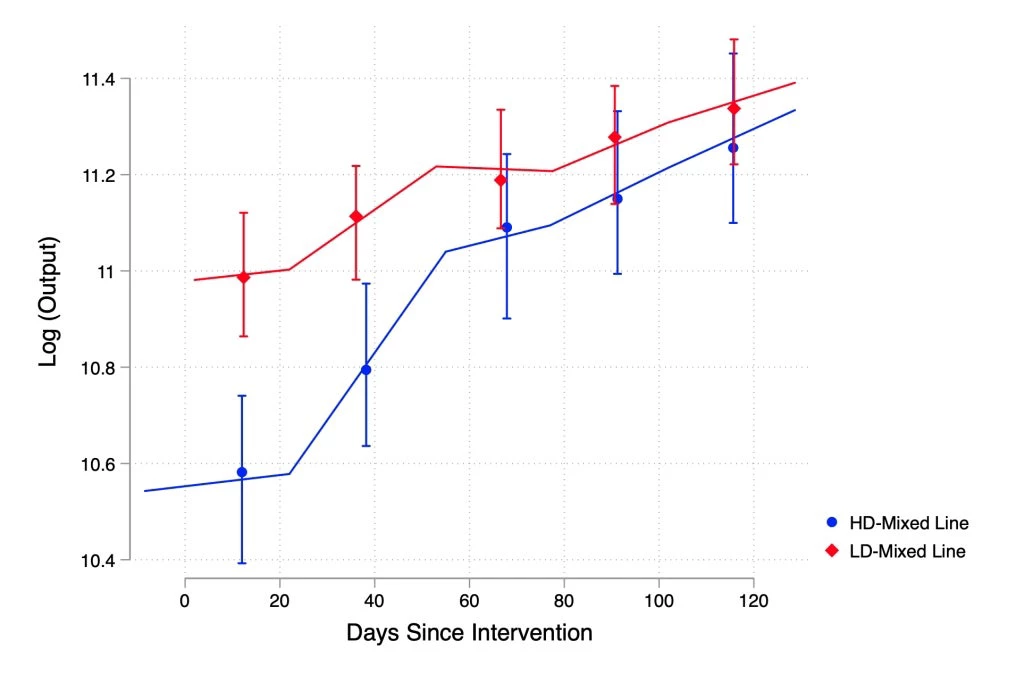

Figure 3: Ethnic Diversity and the Manufacturing Sector (Cross-Country)

Data Source: World Bank and Historical Index of Ethnic Fractionalization (HIEF)

Note: GDP per capita is controlled for in this figure.

Could this be an explanation for why ethnically diverse countries have smaller manufacturing sectors, even after controlling for income (Figure 3)? I plan to now conduct a large-scale survey with firm owners and workers across India to understand how firms with different production functions deal with (the effects of) diversity. This will be an attempt at understanding if/how the interaction between production technology and ethnic diversity matters for broader economic change.

Arkadev Ghosh is a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia.

Join the Conversation