That’s one blunt message from my new working paper with Marcel Fafchamps, Simon Quinn and Chris Woodruff, which replicates in Ghana a study that Chris and I had previously done in Sri Lanka with Suresh de Mel. In the new experiment, we take almost 800 microenterprises in urban Ghana, and randomly divide them into treatment and control groups. Half of the treatment group are given a cash grant of 150 cedis, which they are free to spend how they like, while the other half are given a grant in the form of raw materials, inventories, or equipment for their business.

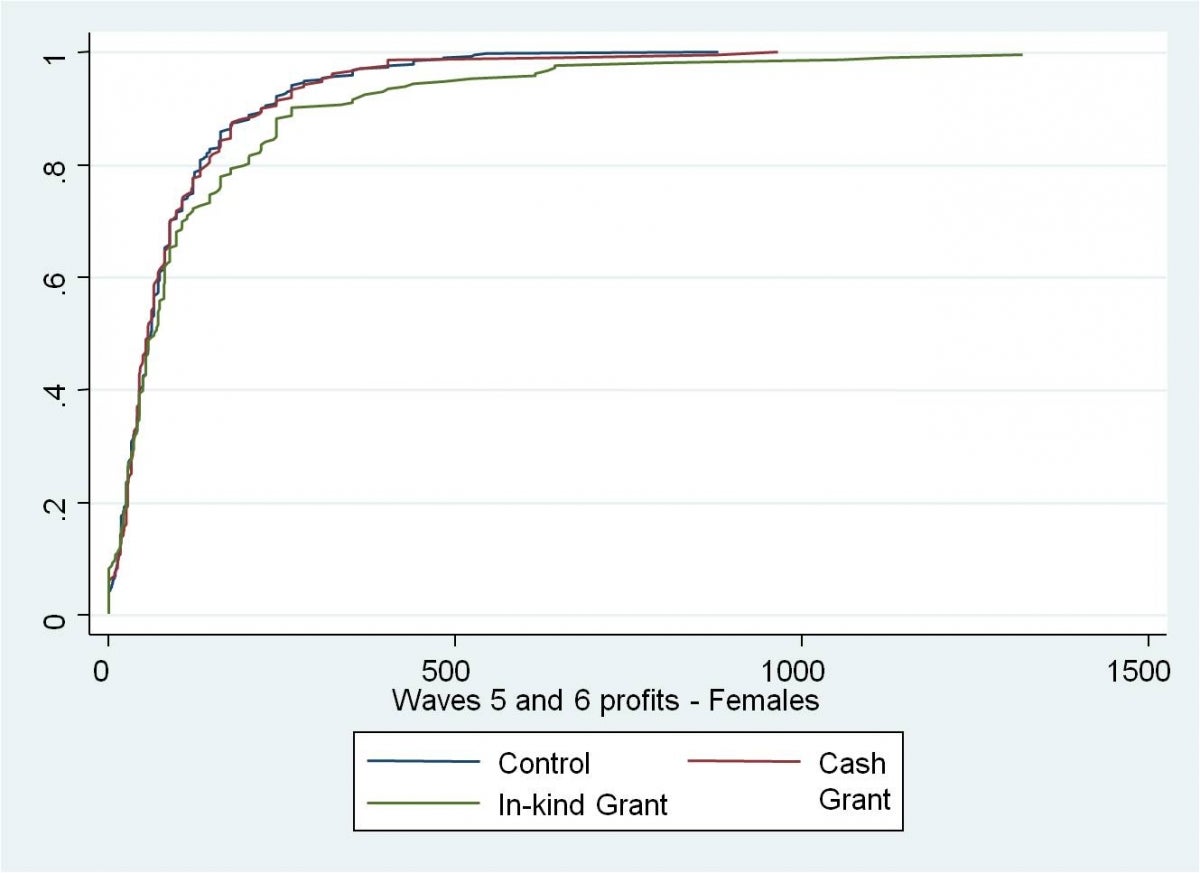

This picture shows the results for women quite starkly: the plot is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of profits for the three groups in the last rounds of the follow-up surveys. The distributions look identical for both treatments and the control for the bottom 60% of women – these are subsistence businesses earning $1 a day on average. In contrast, the in-kind treatment has had positive impacts at the top of the distribution, whereas the cash treatment distribution continues to look like the control. i.e.

· For subsistence women (earning $1 a day), neither cash nor in-kind grants leads to any increase in profits

· For women with higher levels of profits, the in-kind grants increase profits by quite a lot, but the cash grant has no effect on business profits.

A common criticism of experiments is that the focus on average treatment effects ignores important distributional results. Indeed the average impact of the in-kind grant is positive and significant for women here, so if we just looked at that, we’d say the in-kind grants were very successful. The CDFs here provide a nice check to see where the distribution has changed. One problem though is that it only tells us whether poor or richer businesses are the ones that benefit more or less under a rank invariance assumption – i.e. if we assume that microenterprises do not change their order in the profits distribution as a result of the treatment. So to formalize the idea that it is the subsistence businesses who see no effect, and the higher initial profit businesses which benefit, we look at treatment effect heterogeneity according to the initial level of profits, and find the results are consistent with the Figure and bullet points above.

So why the difference between cash and in-kind grants? Most of the in-kind grants were used for working capital, so should have been relatively easy to convert to cash. They therefore differ in very short-term liquidity, and in where they initially went. Self-control issues or external pressure to share could then lead to a difference in outcomes – we explore both channels, and find the evidence seems to support more the idea that self-control is the problem – and that by forcing the grants into the business with an in-kind grant, we can overcome this constraint for firms who have scope to grow, thereby improving business outcomes.

More details on the experiment and its policy implications can be found in a 2-page summary in the latest Finance & PSD Impact note series.

Methodologically, there are a few things in the paper that I thought might be of interest to others designing impact evaluations:

· Instead of just doing a single baseline and follow-up, we did two rounds of surveys pre-treatment, and four rounds post-treatment. This enabled us to increase power substantially compared to what would be possible with the standard baseline and follow-up (see this paper).

· We stratified on several key variables, and then formed matched quadruplets according to round 2 profits before randomizing. This improves power further and gives greater balance on the baseline outcome of interest than would likely be the case under pure randomization. One lesson for us for next time – we ended up with chance imbalance on round 1 profits for males getting the cash treatment, so next time with multiple waves I would match on both round 1 and round 2 pre-treatment profits.

· We used PDAs to collect the profit data, and programmed in consistency checks to improve accuracy. One check was that in waves 2 onwards, we calculated the changes in profits compared to the prior round, and then queried firms if these changes were large. This reduced the noise slightly in this outcome, but one interesting finding from this exercise was that the majority of large changes in profits were upon checking, verified by firm owners as indeed the genuine variability they face (see this paper forthcoming in the JDE for more on this).

· David Card, Stefano DellaVigna and Ulrike Malmendier have made a plea for the use of experiments to test competing models of theories more often – here we use the experiment to test three competing models of firm investment behavior, and reject a standard Ramsey model in favor of a model with a lack of asset integration, in which the form that capital comes in determines how it is used in the business.

Join the Conversation