This is the thirteenth in this year's series of posts by PhD students on the job market.

Our planet is currently experiencing substantial environmental degradation. The resulting depletion of resources and climate change patterns endanger the prospects for human life on earth in the long run, but there are often detrimental consequences that materialize sooner. While governments might have little incentive to reign in dangerous practices if the effects are not expected to emerge until the future, the recognition of concurrent costs might provide more urgency to the need to stem environmental harms. In my job market paper, I document an immediate human health impact of the rapid rates of deforestation in Indonesia, one that arises due to forest loss-induced spikes in malaria.

Indonesia is an important setting to study this issue. The country has one of the largest stretches of tropical forests, but it has recently come to exhibit the highest global increase in deforestation (Hansen et al., 2013). Between 2000 and 2008, the time period I examine in this study, Indonesia lost almost 50,000 square kilometres of forests, or double the area of the US state of Vermont (Burgess et al, 2012). Given that Indonesia is the fourth most populous nation in the world, any detrimental health effects of forest loss are likely to be substantial.

Deforestation and malaria

Deforestation can influence malaria prevalence through various channels. For example, forest loss tends to engender biodiversity losses, and the resulting reduction or elimination of species that feed on mosquitos and/or mosquito larvae leads to the proliferation of malaria vectors. Deforestation can also increase ground temperatures, thus aiding malaria transmission (Pattanayak and Pfaff, 2009). In line with evidence from different parts of the world (Olson et al., 2010; Fornace et al., 2016; Berazneva and Byker, 2017), studies in Indonesia have found a positive relationship between deforestation and malaria incidence in protected forest regions (Pattanayak et al., 2010; Garg, 2017). However, it isn’t clear whether malaria increases due to forest loss in the country have been severe enough to bring about mortality, which is what I probe in this analysis and I do so specifically with regard to infants.

Research strategy

Forest loss is likely to be accompanied with various changes and these could shape health in different ways. Forests are often cleared with fires and the resulting air pollution is detrimental to health (Frankenberg et al, 2005; Jayachandran, 2009). On the other hand, the expansion of palm oil cultivation, which is responsible for much deforestation in Indonesia, has been found to have poverty-reduction effects (Edwards, 2018) and could thus improve health outcomes.

In order to separate out the mortality effects of malaria from the potential impacts of other mechanisms, I use a difference-in-differences approach that contrasts two groups of infants who are likely to react similarly to everything that occurs concurrently with forest loss but who differ in their propensity for being affected by malaria. Pregnant women, who are very vulnerable to malaria, are at a higher risk for poor birth outcomes, such as low birth weight, because of the disease. These outcomes, in turn, increase the likelihood of infant mortality. While individuals in malaria-endemic nations (such as Indonesia) are likely to develop some resistance to the disease due to recurrent infections, the placenta that is created during a woman’s first pregnancy is a new organ with no exposure to the disease and so women are most susceptible to malaria at this time. During subsequent pregnancies, women benefit from antibodies created in previous pregnancies and the malaria risks decline. As a result of this pattern, firstborn children are much more likely to experience the brunt of maternal malaria’s effects than later born children (Steketee et al., 2001; Lucas, 2013). Importantly, of all the potential consequences of deforestation (such as air pollution and poverty reductions), only malaria is known to have differential effects by birth order.

Combining the variation in maternal malaria’s consequences for first and later born children with forest cover variation over time allows me to use a difference-in-differences framework for my analysis. Essentially, I compare the change in firstborn mortality when districts go from having high to low forest cover with the same change for later born children. This approach likely underestimates the total infant mortality costs of deforestation-induced malaria since it is unable to capture the costs borne by later born children, which while lower than that for firstborn children, are unlikely to be zero.

Pulling child-level data from several rounds of the Demographic and Health Surveys in Indonesia, I link each child to the forest levels that prevailed in the district and year in which the child’s mother was pregnant with the child. The 2000-2008 annual forest data that I use is from Burgess et al. (2012) and is available for all districts in Indonesia’s forested regions. The highlighted regions in Figure 1 are those covered by this data.

Results

I find that a firstborn child is more likely to die than a later born child when forest cover declines. When district forest cover falls one standard deviation below mean forest levels within the district during the study period, first infant mortality increases by one percentage point. Back-of-the-envelope calculations indicate that the loss of a standard deviation of forests in all study districts in a year is responsible for 7,463 deaths among live first births in Indonesia (or 35% of all annual deaths in this sub-group). Since only malaria imposes a disproportionate burden on firstborn children, these deaths can plausibly be attributed to the disease.

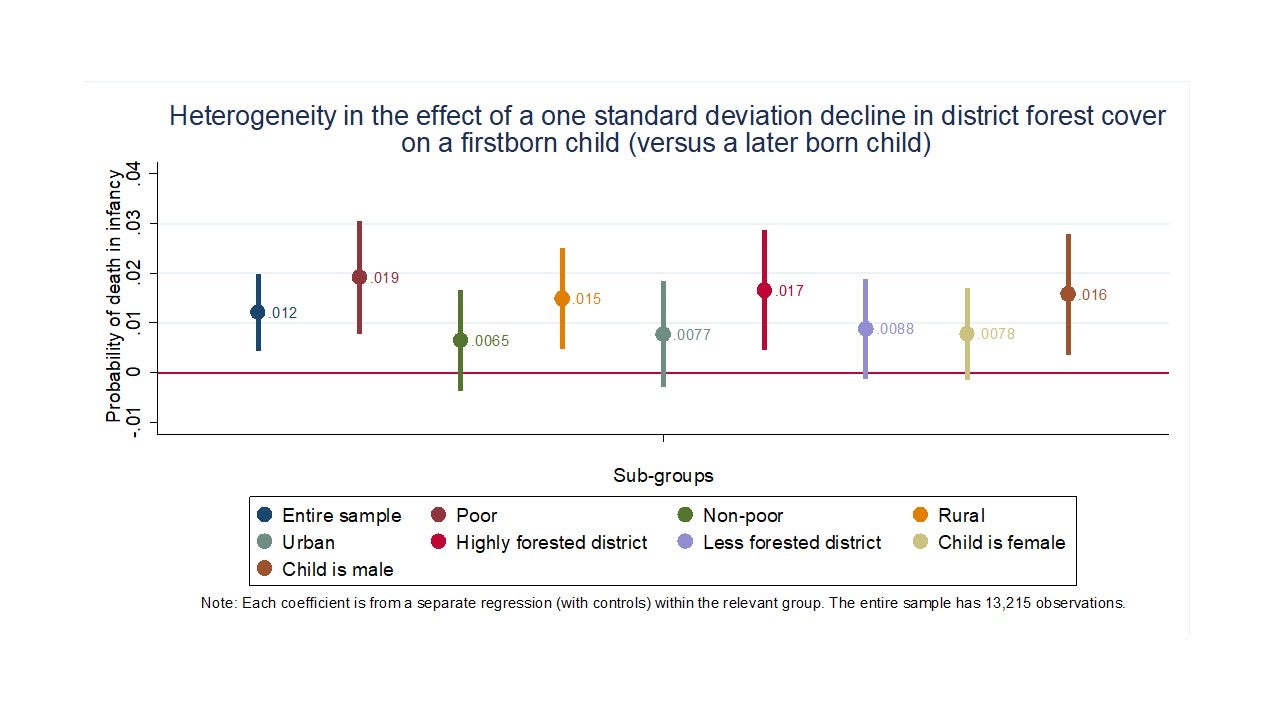

Results depicted in Figure 2 suggest that some groups might be especially vulnerable to malaria increases from deforestation—the poor, rural residents, and those who live in districts with high initial forest levels—presumably because they live in close proximity to and/or are dependent on forested areas for their livelihoods or sustenance. I also find that deforestation during the prenatal period might be more harmful for boys than girls, likely due to the former’s higher susceptibility to in utero shocks (Kraemer, 2000). Furthermore, I observe that malaria risks emerge when deforestation occurs in the primary forest regions (dense forests that are supposed to be conserved) but not when it takes place in secondary forest regions (fragmented forests where some logging is permitted), which is consistent with past evidence (Pattanayak et al., 2010; Garg, 2017).

Alternative explanations

I explore whether other contemporaneous changes in Indonesia shape firstborn and later born children differently. A disparity in survival odds could emerge, for example, if any birth order-specific differences in health care access (such as receipt of vaccines) track forest cover changes. I do not find evidence of such systematic differences.

Policy implications

Edwards (2018) finds that the expansion of palm oil production in Indonesia has brought economic benefits to the country, but has also been responsible for substantial forest cover declines. The results of my analysis underscore the mortality and morbidity costs that this kind of environmental degradation imposes on local populations. These detrimental effects should be factored into policy decisions regarding the use of forest resources.

In order to address the threats to health emerging due to forest deterioration and disappearance in Indonesia, there is need to scale up anti-malaria programs such as bed net distribution. Since my results suggest that malaria due to forest loss increases mortality for firstborn infants, these initiatives should target young women around the mean age at first birth in areas being deforested.

Averi Chakrabarti is a PhD Candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Join the Conversation