Amidst momentous

political and

economic

reforms, the Ethiopian labor market continues to shift from low-productivity agriculture to services, construction, and tradables. Urbanization is a key aspect of this transformation, as people from rural areas seek employment and education in the cities.

In the outskirts of the capital Addis Ababa, where a lot of rural-urban migrants settle, one starting point into the city’s formal labor market is the country’s burgeoning ready-made garment industry . Ethiopia represents one of the lowest-cost manufacturing destinations in the world. Firms tend to pay extremely low wages clustered around the local poverty line. They offer little to no upward mobility, so that the vast majority of workers will not advance past the level of machine operators. With its low but stable wages and almost no skill requirements, the ready-made garment industry provides what Blattman and Dercon have called an “industrial safety net.”

When you ask garment workers what they hope to get out of their jobs, they will describe them as a stepping stone to a better life. Many workers see the job as temporary and want to continue searching for better opportunities. It also appears, however, that throughout their employment spell many workers struggle to follow through on their intention to search and move on. In my job market paper , I document how self-control problems undermine workers’ job search efforts. That, in turn, might get them stuck in their jobs. I show this with detailed panel data that I collect from 460 women who start homogeneous production jobs in an industrial park in the outskirts of Addis Ababa. I first use a tightly-controlled lab-in-the-field experiment on the day that workers join the firm to elicit potential self-control problems in the form of present bias. I then correlate the experimental results with subsequent choices over job search effort.

I find that workers who have self-control problems in the form of present bias spend on average 57 percent less time on job search. As an immediate consequence of less search, they generate fewer job offers and ultimately stay in their jobs significantly longer. This finding can be seen as complementary to work by Atkin (2016), who shows that workers in Mexican maquiladoras took present-biased decisions by choosing short-term gains at work over long-term gains through schooling. It appears that present bias not only makes workers take low-skill industrial jobs – it also keeps workers in these jobs.

My findings also offer a counterpoint to the notion that churn in these low-skill industrial jobs is higher than optimal. Some ongoing work has looked into how we can reduce churn in order to reduce hiring costs for employers. While this was not the focus of my paper, future work should carefully think about welfare implications both for firms and for workers.

First experimental evidence on self-control problems in job search

Prominent models that formalize self-control problems provide two key predictions. First, people with self-control problems have characteristic consumption patterns. They consume too little of a good with immediate costs and future rewards (such searching for a job) and too much of a good with immediate rewards and future costs (such as enjoying leisure time). Second, people who are aware of their self-control problems may want to tie their own hands. While the literature has established this demand for commitment in many domains ( savings in general, savings for health, savings for retirement, gym attendance, investments into fertilizers, stopping to smoke, and working harder), evidence on the hypothesized link between self-control problems and the consumption patterns described above is relatively scarce. My paper studies the link between self-control problems and job search behavior. This link has previously been explored theoretically and empirically by DellaVigna and Paserman (2005). To the best of my knowledge, my paper provides the first direct experimental evidence.

Methods: Lab-in-the-field experiment combined with high-frequency survey data

To formalize self-control problems, I use quasi-hyperbolic (β-δ) preferences ( Laibson 1997; O’Donoghue and Rabin, 1999). In the standard exponential discounted utility framework, every future period is discounted by a constant discount factor δ. In the quasi-hyperbolic framework, an additional present bias parameter β allows for higher discounting between the current and the next period. This β is the parameter of interest in my analysis.

Theoretically, I think of on-the-job search in this context as a self-insurance mechanism. In a simple model, one can show that an increase in present bias reduces the present value of search and thus search effort. As a corollary, present-biased workers stay longer at the firm. The model illustrates how workers may experience a “behavioral job-lock,” where voluntary turnover is reduced due to self-control problems.

To estimate present bias and other parameters of each worker’s utility function, I use a version of the convex time budget task. On the first day at work, each worker makes 15 allocations of a large experimental budget (20 to 40 percent of the monthly wage) over two points in time. My fieldwork focused on maximizing experimental control and reducing common confounders. This included using Ethiopia’s new mobile money system for precisely-timed and costless experimental payouts. After the baseline lab-in-the-field experiment, I use phone surveys to follow up with each worker every two weeks. I collect detailed information on job search effort and job search outcomes.

Main result: Self-control problems explain lack of search, fewer job offers, longer tenure at the firm

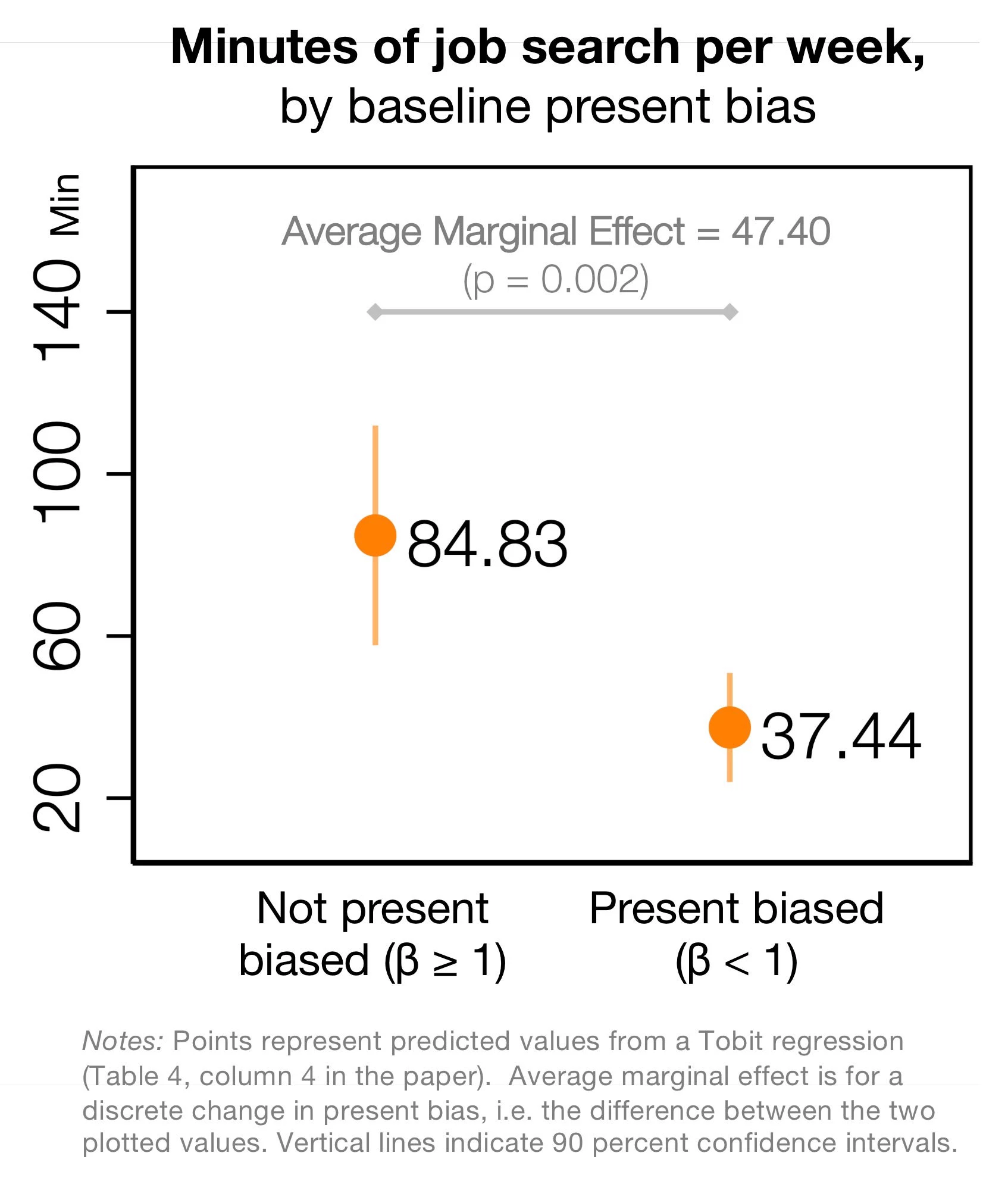

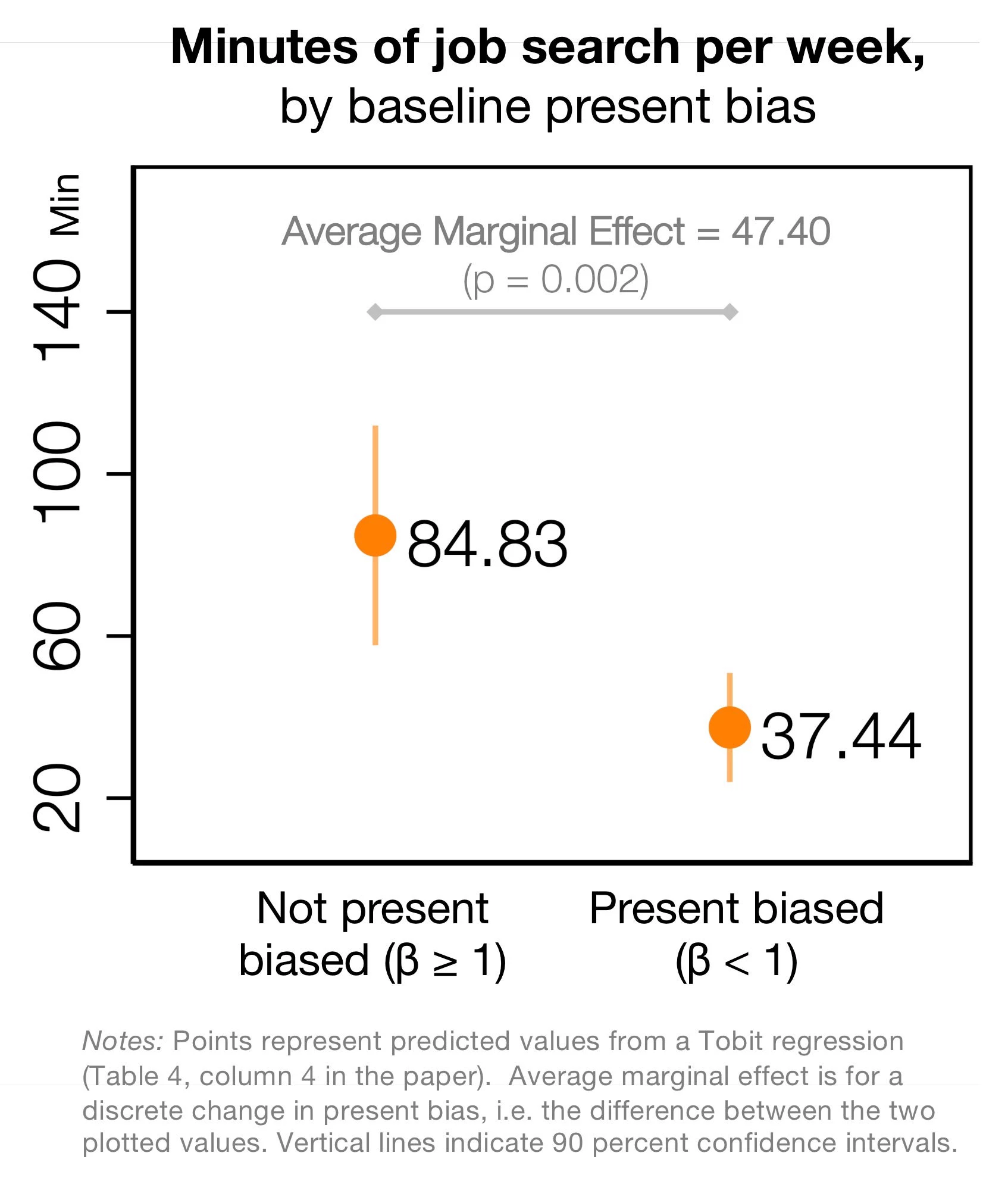

The figure below illustrates the main result for one measure of job search effort: the amount of time spent per week looking for a job. To ease interpretation of results, I use a dummy for whether workers were present-biased in the baseline experimental task (i.e. have an estimated βpresent-biased workers spend on average 37 minutes on job search, compared to 85 minutes for workers who are not present-biased.

…but these are just correlations!

Yes, they are! A clear limitation of my study is that I do not have exogenous variation to provide identification – not least because I first wanted to establish whether self-control problems could explain why workers fail to follow through on their intentions to search. Given that the results are correlational, the paper discusses and rules out a range of possible alternative explanations for my findings. For example, I use randomized cash drops at baseline to show that individual financial wealth and liquidity are unlikely to explain my results. I conclude that present bias offers the most parsimonious explanation for my results, but I would love to discuss alternative explanations in the comments below!

Policy implications and next steps

What should a policymaker do about this? An immediate implication of my findings is that people looking for work might value policies or devices that commit their future selves to more search. Whether and under what conditions such a commitment device can be welfare-improving at the individual or societal level depends on the exact welfare criterion, which can be challenging to define in this context:

Unfortunately, my paper is not equipped to study general equilibrium effects. (Though I aim to better understand those effects through ongoing work with Kevin Croke and Morgan Hardy in Southern Ethiopia.) Rather, I see my paper as a piece of evidence to motivate further work on how cognitive biases may undermine our individual ability to navigate labor markets. Ultimately, targeting ALMPs at individuals who are taking individually-suboptimal decisions might even get around some of the displacement effects that occur with more broadly-targeted interventions.

Christian Johannes Meyer is a PhD student at the European University Institute. You can find out more about his research at www.chrmeyer.com.

In the outskirts of the capital Addis Ababa, where a lot of rural-urban migrants settle, one starting point into the city’s formal labor market is the country’s burgeoning ready-made garment industry . Ethiopia represents one of the lowest-cost manufacturing destinations in the world. Firms tend to pay extremely low wages clustered around the local poverty line. They offer little to no upward mobility, so that the vast majority of workers will not advance past the level of machine operators. With its low but stable wages and almost no skill requirements, the ready-made garment industry provides what Blattman and Dercon have called an “industrial safety net.”

When you ask garment workers what they hope to get out of their jobs, they will describe them as a stepping stone to a better life. Many workers see the job as temporary and want to continue searching for better opportunities. It also appears, however, that throughout their employment spell many workers struggle to follow through on their intention to search and move on. In my job market paper , I document how self-control problems undermine workers’ job search efforts. That, in turn, might get them stuck in their jobs. I show this with detailed panel data that I collect from 460 women who start homogeneous production jobs in an industrial park in the outskirts of Addis Ababa. I first use a tightly-controlled lab-in-the-field experiment on the day that workers join the firm to elicit potential self-control problems in the form of present bias. I then correlate the experimental results with subsequent choices over job search effort.

I find that workers who have self-control problems in the form of present bias spend on average 57 percent less time on job search. As an immediate consequence of less search, they generate fewer job offers and ultimately stay in their jobs significantly longer. This finding can be seen as complementary to work by Atkin (2016), who shows that workers in Mexican maquiladoras took present-biased decisions by choosing short-term gains at work over long-term gains through schooling. It appears that present bias not only makes workers take low-skill industrial jobs – it also keeps workers in these jobs.

My findings also offer a counterpoint to the notion that churn in these low-skill industrial jobs is higher than optimal. Some ongoing work has looked into how we can reduce churn in order to reduce hiring costs for employers. While this was not the focus of my paper, future work should carefully think about welfare implications both for firms and for workers.

First experimental evidence on self-control problems in job search

Prominent models that formalize self-control problems provide two key predictions. First, people with self-control problems have characteristic consumption patterns. They consume too little of a good with immediate costs and future rewards (such searching for a job) and too much of a good with immediate rewards and future costs (such as enjoying leisure time). Second, people who are aware of their self-control problems may want to tie their own hands. While the literature has established this demand for commitment in many domains ( savings in general, savings for health, savings for retirement, gym attendance, investments into fertilizers, stopping to smoke, and working harder), evidence on the hypothesized link between self-control problems and the consumption patterns described above is relatively scarce. My paper studies the link between self-control problems and job search behavior. This link has previously been explored theoretically and empirically by DellaVigna and Paserman (2005). To the best of my knowledge, my paper provides the first direct experimental evidence.

Methods: Lab-in-the-field experiment combined with high-frequency survey data

To formalize self-control problems, I use quasi-hyperbolic (β-δ) preferences ( Laibson 1997; O’Donoghue and Rabin, 1999). In the standard exponential discounted utility framework, every future period is discounted by a constant discount factor δ. In the quasi-hyperbolic framework, an additional present bias parameter β allows for higher discounting between the current and the next period. This β is the parameter of interest in my analysis.

Theoretically, I think of on-the-job search in this context as a self-insurance mechanism. In a simple model, one can show that an increase in present bias reduces the present value of search and thus search effort. As a corollary, present-biased workers stay longer at the firm. The model illustrates how workers may experience a “behavioral job-lock,” where voluntary turnover is reduced due to self-control problems.

To estimate present bias and other parameters of each worker’s utility function, I use a version of the convex time budget task. On the first day at work, each worker makes 15 allocations of a large experimental budget (20 to 40 percent of the monthly wage) over two points in time. My fieldwork focused on maximizing experimental control and reducing common confounders. This included using Ethiopia’s new mobile money system for precisely-timed and costless experimental payouts. After the baseline lab-in-the-field experiment, I use phone surveys to follow up with each worker every two weeks. I collect detailed information on job search effort and job search outcomes.

Main result: Self-control problems explain lack of search, fewer job offers, longer tenure at the firm

The figure below illustrates the main result for one measure of job search effort: the amount of time spent per week looking for a job. To ease interpretation of results, I use a dummy for whether workers were present-biased in the baseline experimental task (i.e. have an estimated βpresent-biased workers spend on average 37 minutes on job search, compared to 85 minutes for workers who are not present-biased.

…but these are just correlations!

Yes, they are! A clear limitation of my study is that I do not have exogenous variation to provide identification – not least because I first wanted to establish whether self-control problems could explain why workers fail to follow through on their intentions to search. Given that the results are correlational, the paper discusses and rules out a range of possible alternative explanations for my findings. For example, I use randomized cash drops at baseline to show that individual financial wealth and liquidity are unlikely to explain my results. I conclude that present bias offers the most parsimonious explanation for my results, but I would love to discuss alternative explanations in the comments below!

Policy implications and next steps

What should a policymaker do about this? An immediate implication of my findings is that people looking for work might value policies or devices that commit their future selves to more search. Whether and under what conditions such a commitment device can be welfare-improving at the individual or societal level depends on the exact welfare criterion, which can be challenging to define in this context:

- Looking at the individual level, a “paternalistic” policymaker might want to level the playing field for people with self-control problems. For such a policymaker, an intervention could be justified as long as she assumes that self-control problems lead to individually sub-optimal decisions (even absent other market failures such as information asymmetries). In context of my study, it is particularly important to balance flexibility and commitment – one should be careful to not trap individuals in a situation that might even decrease their welfare. “Soft” commitment devices that work through psychological mechanisms might hold more promise in that regard than those operating through “hard” monetary costs. Through semi-structured focus group interviews with workers, we identified a few possibilities for such devices. One could be to help workers set up a personal plan for job search. With such a plan, workers could formalize intentions for search and possibly set personal rules for how much to search, when to search, and how to search. Another option could be to facilitate the formation of small groups to exchange knowledge about the labor market and how to search for work, and possibly to benefit from social pressure.

- At the societal level, a planner should think carefully about the effects of an intervention. An important concern with active labor market policies (ALMPs) that promote job search is that they might just change who gets a particular job without creating more jobs. Recent papers have started to uncover negative externalities of such interventions on other workers (Crépon et al. 2013, Gautier et al. 2018). In my context, the general equilibrium effects of an intervention could go both ways: In a labor market where search costs are substantial and queuing for better skilled jobs appears prevalent, it might be beneficial if fewer people “get stuck”. At the same time, more search might lead to congestion that could decrease the aggregate matching rate and leave the labor market worse off on aggregate.

Unfortunately, my paper is not equipped to study general equilibrium effects. (Though I aim to better understand those effects through ongoing work with Kevin Croke and Morgan Hardy in Southern Ethiopia.) Rather, I see my paper as a piece of evidence to motivate further work on how cognitive biases may undermine our individual ability to navigate labor markets. Ultimately, targeting ALMPs at individuals who are taking individually-suboptimal decisions might even get around some of the displacement effects that occur with more broadly-targeted interventions.

Christian Johannes Meyer is a PhD student at the European University Institute. You can find out more about his research at www.chrmeyer.com.

Join the Conversation