“Teacher coaching has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional models of professional development.” In Kraft, Blazar, and Hogan’s newly updated review “

The Effect of Teacher Coaching on Instruction and Achievement: A Meta-Analysis of the Causal Evidence,” they highlight that reviews of the literature on teacher professional development (i.e., training teachers who are already on the job) highlight a few promising characteristics of effective programs:

Teacher coaching focuses on several of these features. While training sessions may improve teacher knowledge, it may be difficult to translate that new knowledge into practice without further support. Coaching programs seek to provide that. Here’s a working definition of coaching: “We characterize the coaching process as one where instructional experts work with teachers to discuss classroom practice in a way that is (a) individualized – coaching sessions are one-on-one; (b) intensive – coaches and teachers interact at least every couple of weeks; (c) sustained – teachers receive coaching over an extended period of time; (d) context-specific – teachers are coached on their practices within the context of their own classroom; and (e) focused – coaches work with teachers to engage in deliberate practice of specific skills.” Kraft et al. distinguish coaching from mentoring and peer-to-peer feedback. Mentoring is often part of the induction process for new teachers and may focus on a wide range of challenges, and peer-to-peer feedback may function differently from an expert coach helping a teacher to implement a specific set of skills.

What do they find?

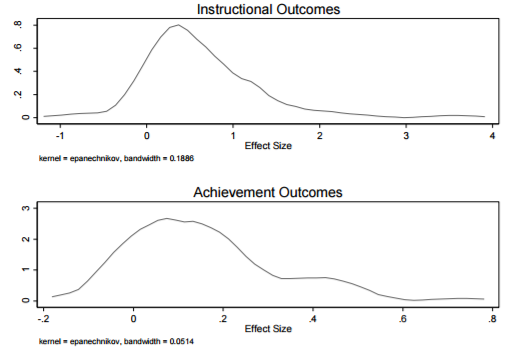

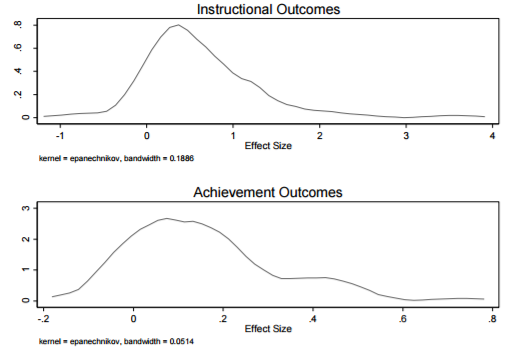

They identified 44 studies (all based in the U.S.) with either teacher instructional outcomes or student learning outcomes. All 44 came out from 2006 onward, so this is a young literature. And of those 44, only 2 studies had a sample of more than 300 teachers; 19 studies had 100+ teachers. Almost all (91 percent) combined coaching with some other element of teacher professional development, whether group training or instructional materials or example videos of high-quality instruction. On average, they find big improvements in teacher instruction (0.58 standard deviations, although it’s tough to say what a “standard deviation in the quality of teacher instruction” really means), and more modest improvements in student learning (0.15 standard deviations). As you can see in the figure below, the distribution of outcomes varied a great deal across studies. They don’t find any significant differences in outcomes based on program characteristics (e.g., virtual versus in-person), but the sample size is small for identifying those effects, so I’d put that in the “insufficient data” category. But they do find relatively precise zeros on total hours of coaching and on total hours of professional development (when coaching is combined with other things). As the authors note, “the quality and focus of coaching may be more important than the actual number of contact hours.”

Source: Kraft et al. 2017.

They do a number of robustness checks (for study design and for publication bias, for example); the story remains the same.

Does instruction actually matter?

Since the authors look at coaching interventions and their impact on both instruction and on learning, they can then check whether the quality of instruction seems to be linked to learning. They only have 11 studies, but they see a strong relationship. “Using a simple linear regression framework, we estimate that a 1 SD change in instruction is associated with a .33 SD change in achievement (p = .07).” Phew! That’s not a surprising finding, but it’s a reassuring one.

What about when you go to scale?

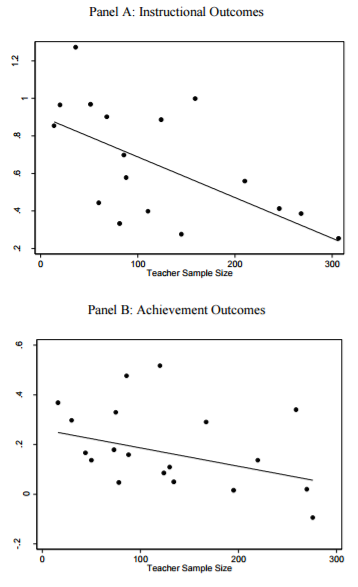

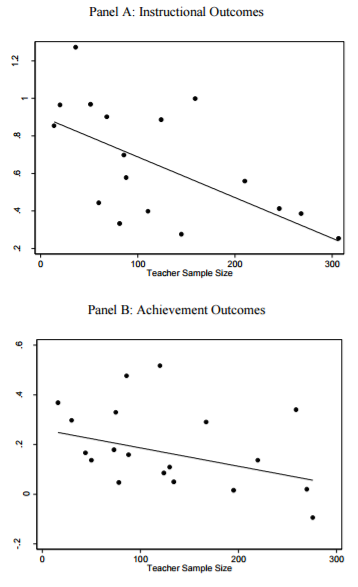

They divide their sample into larger programs (100+ teachers) and smaller programs (less than 100). Most of the smaller programs actually had 50 or fewer teachers. The impact on instructional quality is 1.5 times higher for smaller programs, and the impact on student learning is twice as high for smaller programs; check out the figures below. So going to scale is – unsurprisingly – a challenge.

Source: Kraft et al. 2017.

The authors highlight that one major challenge is finding sufficient coaches! Using highly effective teachers as coaches has the downside that they themselves are teaching less. Virtual coaching could help by reducing travel time. One coaching program for pre-school teachers found similar effects for on-site delivery versus remote delivery, but clearly (1) this requires more study, and (2) many low- and middle-income contexts don’t have sufficiently consistent connectivity to support virtual coaching.

Another challenge is teacher buy-in. Small-scale pilot programs may be carried out in areas with a teaching culture more open to critique. Effectively implementing this kind of program at scale will require growing cultures where teachers accept and seek to incorporate suggestions on how to do better.

The authors provide many helpful recommendations for future research in this area.

What about low- and middle-income environments?

The literature is much smaller outside of high-income countries. Piper and Zuilkowski find positive results of coaching in a study of several hundred schools in Kenya. (A nationally scaled-up version of the program has no comparison group; an initial evaluation shows significant learning happening, but more analysis will be needed to understand how much of that learning is attributable to the program.) A tiny intervention in Thailand had positive impacts on instructional quality. A program in Malawi led teachers to believe they were more competent, but instructional quality didn’t change. And a program in Brazil that used Skype to deliver coaching to 175 schools led to average gains in student learning, with sizeable gains in schools with high-quality implementation.

Take away: Coaching can be an effective way to improve teacher practice and student learning. Implementing it effectively at scale remains a challenge. But there are interesting approaches underway.

- Practice on the job

- Substantive length and intensity of training

- Focus on specific sets of skills

- Active learning

Teacher coaching focuses on several of these features. While training sessions may improve teacher knowledge, it may be difficult to translate that new knowledge into practice without further support. Coaching programs seek to provide that. Here’s a working definition of coaching: “We characterize the coaching process as one where instructional experts work with teachers to discuss classroom practice in a way that is (a) individualized – coaching sessions are one-on-one; (b) intensive – coaches and teachers interact at least every couple of weeks; (c) sustained – teachers receive coaching over an extended period of time; (d) context-specific – teachers are coached on their practices within the context of their own classroom; and (e) focused – coaches work with teachers to engage in deliberate practice of specific skills.” Kraft et al. distinguish coaching from mentoring and peer-to-peer feedback. Mentoring is often part of the induction process for new teachers and may focus on a wide range of challenges, and peer-to-peer feedback may function differently from an expert coach helping a teacher to implement a specific set of skills.

What do they find?

They identified 44 studies (all based in the U.S.) with either teacher instructional outcomes or student learning outcomes. All 44 came out from 2006 onward, so this is a young literature. And of those 44, only 2 studies had a sample of more than 300 teachers; 19 studies had 100+ teachers. Almost all (91 percent) combined coaching with some other element of teacher professional development, whether group training or instructional materials or example videos of high-quality instruction. On average, they find big improvements in teacher instruction (0.58 standard deviations, although it’s tough to say what a “standard deviation in the quality of teacher instruction” really means), and more modest improvements in student learning (0.15 standard deviations). As you can see in the figure below, the distribution of outcomes varied a great deal across studies. They don’t find any significant differences in outcomes based on program characteristics (e.g., virtual versus in-person), but the sample size is small for identifying those effects, so I’d put that in the “insufficient data” category. But they do find relatively precise zeros on total hours of coaching and on total hours of professional development (when coaching is combined with other things). As the authors note, “the quality and focus of coaching may be more important than the actual number of contact hours.”

Source: Kraft et al. 2017.

They do a number of robustness checks (for study design and for publication bias, for example); the story remains the same.

Does instruction actually matter?

Since the authors look at coaching interventions and their impact on both instruction and on learning, they can then check whether the quality of instruction seems to be linked to learning. They only have 11 studies, but they see a strong relationship. “Using a simple linear regression framework, we estimate that a 1 SD change in instruction is associated with a .33 SD change in achievement (p = .07).” Phew! That’s not a surprising finding, but it’s a reassuring one.

What about when you go to scale?

They divide their sample into larger programs (100+ teachers) and smaller programs (less than 100). Most of the smaller programs actually had 50 or fewer teachers. The impact on instructional quality is 1.5 times higher for smaller programs, and the impact on student learning is twice as high for smaller programs; check out the figures below. So going to scale is – unsurprisingly – a challenge.

Source: Kraft et al. 2017.

The authors highlight that one major challenge is finding sufficient coaches! Using highly effective teachers as coaches has the downside that they themselves are teaching less. Virtual coaching could help by reducing travel time. One coaching program for pre-school teachers found similar effects for on-site delivery versus remote delivery, but clearly (1) this requires more study, and (2) many low- and middle-income contexts don’t have sufficiently consistent connectivity to support virtual coaching.

Another challenge is teacher buy-in. Small-scale pilot programs may be carried out in areas with a teaching culture more open to critique. Effectively implementing this kind of program at scale will require growing cultures where teachers accept and seek to incorporate suggestions on how to do better.

The authors provide many helpful recommendations for future research in this area.

What about low- and middle-income environments?

The literature is much smaller outside of high-income countries. Piper and Zuilkowski find positive results of coaching in a study of several hundred schools in Kenya. (A nationally scaled-up version of the program has no comparison group; an initial evaluation shows significant learning happening, but more analysis will be needed to understand how much of that learning is attributable to the program.) A tiny intervention in Thailand had positive impacts on instructional quality. A program in Malawi led teachers to believe they were more competent, but instructional quality didn’t change. And a program in Brazil that used Skype to deliver coaching to 175 schools led to average gains in student learning, with sizeable gains in schools with high-quality implementation.

Take away: Coaching can be an effective way to improve teacher practice and student learning. Implementing it effectively at scale remains a challenge. But there are interesting approaches underway.

Join the Conversation