Across low-income countries,

fewer than one in every three girls are enrolled in secondary school. Many interventions to improve girls’ access to school provide cash, such as cash transfers in

Malawi or

Nepal. But what if girls had better skills to advocate for their own interests? In a recent experiment in Zambia, Nava Ashraf, Natalie Bau, Corinne Low, and Kathleen McGinn tested what happens when adolescent girls receive negotiation training. The results are documented in their paper, “

Negotiating a Better Future: How Interpersonal Skills Facilitate Inter-Generational Investment.” Over the course of six two-hour after-school sessions, eighth-grade girls engaged in discussion, role-playing, storytelling, and game play to learn four principles of negotiation from college educated Zambian women.

"I asked my parents if they could talk with me. I put on my chitenge [traditional material skirt], and knelt before them. I chose to approach with respect and so they asked me to stand and sit in the chair near them and tell them what I wanted to say. I said that I really wanted to be able to go back to school but wasn't able to because the school fees weren't paid. They said I knew that the family had no more money so it wasn't possible. I said I know that mom sells chickens out of the house. I see that some people sell them in the marketplace nearby. If I can sell some chickens in the market over the school holiday, could I use the money for my school fees? They agreed and that is how I got to go back to school."

You can see how she put the principles together: Me – she identified her interest: go back to school. You – she approached her parents with respect and listened to their concern. Together – she saw that the “no” wasn’t from a lack of desire from her parents but from an external obstacle. Build – she proposed a win-win situation. Not every negotiation is about school fees. One girl recounted using the skills to push back against her boyfriend’s demands for sex. Another wrote about negotiation with her sister to exchange child care for hair styling.

Two months after the negotiation training, the girls who participated (“negotiators”) scored much better on an open-ended test of how to find time to study for an exam when a younger brother needed watching. Over the course of the next couple of years, dropout rates were ten percentage points lower for negotiators, and attendance – for girls enrolled in school – was slightly higher. Although some other outcomes – performance in the top quarter on math and English tests and reported pregnancy rates – remained unchanged, an index of all the effects together improves, even when the enrollment effects are excluded. (When interpreting the lack of a pregnancy effect, keep in mind that reported pregnancies in the compaision group are already very low, just 4 percent.) The negotiation skills kept girls in school. Parents reported that negotiators were more likely to ask for more food and did fewer weekday chores; but they also reported that negotiators were more respectful, less likely to give difficulty in doing the chores they had, and more likely to do chores on Fridays – when schoolwork is less pressing.

For the girls with the highest language ability at baseline, the effects on enrollment and attendance are even stronger, and performance on an English test also rose.

But wait, is it really the negotiation skills? Maybe exposure to these college-educated Zambian mentors in a safe space is what’s actually driving these findings. Or maybe interacting with that mentor simply provided better information about the returns to education, which we know can keep youth in school. To test this, the researchers tried two other interventions: one with the same mentors and the same safe space but no negotiation training, and a second that provided information on the returns to education and on HIV prevention. The information intervention had no impact on any outcomes, and the safe space intervention had a similar – slightly smaller – impact on enrollment to the negotiation program, and lower estimated impacts on every other impact (albeit not statistically significantly different). The safe space intervention also had almost no impact on parent reports about the child’s behavior and chores at home.

But wait (again!), does this harm the other children in the household? The researchers look for impacts on other children in the school and in the household and find little evidence of negative spillovers. It didn’t affect the distribution of chores and if anything, it increased the amount of time parents expected sisters of the negotiators to do their own schoolwork. Parents of negotiators do report a higher likelihood to pay girls’ school fees over those of boys, but they don’t reduce the expected years of education for boys in the household. As the authors put it, “While it may seem surprising that increased educational investment in the treated girl did not negatively affect her siblings, this could be because the increased investment came out of parents' consumption or because girls used negotiation to arrive at solutions that increased family welfare.”

There’s much more in the paper, including lab-in-the-field games to show how the program affected interactions between parents and children, and machine learning techniques to shape the heterogeneity analysis. But this intervention shows that adolescents can learn valuable socio-emotional skills, working through the education system.

Most directly, it demonstrates that it’s possible to help girls to stay in school by making them more effective advocates for themselves.

For more about the program, you can read this story on NPR’s Goats and Soda blog.

-

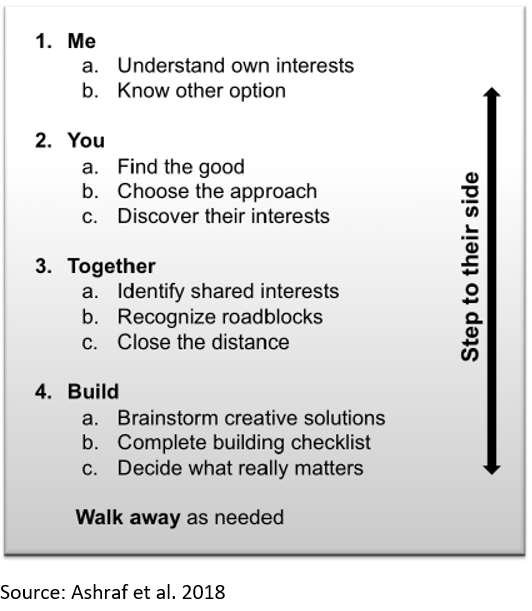

Principle 1: Me. The girls learned to understand their own interests, identify their back-up plan, when to walk away during a negotiation (when options don’t meet the girls’ needs), and how to regulate emotion by taking a short break when anger gets in the way of good bargaining.

Principle 1: Me. The girls learned to understand their own interests, identify their back-up plan, when to walk away during a negotiation (when options don’t meet the girls’ needs), and how to regulate emotion by taking a short break when anger gets in the way of good bargaining. - Principle 2: You. The girls learned to ask open-ended questions to understand the interests of the other person and to approach the other person respectfully.

- Principle 3: Together. The girls were taught to identify common ground with the other person, and to identify if a “no” from the other person came from some external obstacle that the girl and the person could resolve together.

- Principle 4: Build. The girls learned to find “win-win” agreements.

"I asked my parents if they could talk with me. I put on my chitenge [traditional material skirt], and knelt before them. I chose to approach with respect and so they asked me to stand and sit in the chair near them and tell them what I wanted to say. I said that I really wanted to be able to go back to school but wasn't able to because the school fees weren't paid. They said I knew that the family had no more money so it wasn't possible. I said I know that mom sells chickens out of the house. I see that some people sell them in the marketplace nearby. If I can sell some chickens in the market over the school holiday, could I use the money for my school fees? They agreed and that is how I got to go back to school."

You can see how she put the principles together: Me – she identified her interest: go back to school. You – she approached her parents with respect and listened to their concern. Together – she saw that the “no” wasn’t from a lack of desire from her parents but from an external obstacle. Build – she proposed a win-win situation. Not every negotiation is about school fees. One girl recounted using the skills to push back against her boyfriend’s demands for sex. Another wrote about negotiation with her sister to exchange child care for hair styling.

Two months after the negotiation training, the girls who participated (“negotiators”) scored much better on an open-ended test of how to find time to study for an exam when a younger brother needed watching. Over the course of the next couple of years, dropout rates were ten percentage points lower for negotiators, and attendance – for girls enrolled in school – was slightly higher. Although some other outcomes – performance in the top quarter on math and English tests and reported pregnancy rates – remained unchanged, an index of all the effects together improves, even when the enrollment effects are excluded. (When interpreting the lack of a pregnancy effect, keep in mind that reported pregnancies in the compaision group are already very low, just 4 percent.) The negotiation skills kept girls in school. Parents reported that negotiators were more likely to ask for more food and did fewer weekday chores; but they also reported that negotiators were more respectful, less likely to give difficulty in doing the chores they had, and more likely to do chores on Fridays – when schoolwork is less pressing.

For the girls with the highest language ability at baseline, the effects on enrollment and attendance are even stronger, and performance on an English test also rose.

But wait, is it really the negotiation skills? Maybe exposure to these college-educated Zambian mentors in a safe space is what’s actually driving these findings. Or maybe interacting with that mentor simply provided better information about the returns to education, which we know can keep youth in school. To test this, the researchers tried two other interventions: one with the same mentors and the same safe space but no negotiation training, and a second that provided information on the returns to education and on HIV prevention. The information intervention had no impact on any outcomes, and the safe space intervention had a similar – slightly smaller – impact on enrollment to the negotiation program, and lower estimated impacts on every other impact (albeit not statistically significantly different). The safe space intervention also had almost no impact on parent reports about the child’s behavior and chores at home.

But wait (again!), does this harm the other children in the household? The researchers look for impacts on other children in the school and in the household and find little evidence of negative spillovers. It didn’t affect the distribution of chores and if anything, it increased the amount of time parents expected sisters of the negotiators to do their own schoolwork. Parents of negotiators do report a higher likelihood to pay girls’ school fees over those of boys, but they don’t reduce the expected years of education for boys in the household. As the authors put it, “While it may seem surprising that increased educational investment in the treated girl did not negatively affect her siblings, this could be because the increased investment came out of parents' consumption or because girls used negotiation to arrive at solutions that increased family welfare.”

There’s much more in the paper, including lab-in-the-field games to show how the program affected interactions between parents and children, and machine learning techniques to shape the heterogeneity analysis. But this intervention shows that adolescents can learn valuable socio-emotional skills, working through the education system.

Most directly, it demonstrates that it’s possible to help girls to stay in school by making them more effective advocates for themselves.

For more about the program, you can read this story on NPR’s Goats and Soda blog.

Join the Conversation