There is no intervention that I know about in development that has the potential to raise living standards as much as moving from a poorer to a richer place does. But we know far more about the benefits of migration than we do about successful ways to change migration decisions. Changing migration policies involves many actors and can be very difficult. I’ve seen this issue come up in the Effective Altruism debate where I’ve seen arguments that basically see the only room for individual donors to support more migration as spending money on lobbying for better migration laws, without much evidence on how successful such spending would be.

We definitely should not give up on trying to push for better migration laws that provide more legal opportunities for people to migrate. There is an important role for researchers in providing evidence to support such efforts, and for international organizations and governments to push for action in this area. Hopefully the recently released World Development Report on Migration and Refugees can spur more such efforts.

But if you are an individual researcher, NGO, or developing country government looking for how you might intervene given the current policy environment, what else can be done? In a forthcoming handbook chapter, Dean Yang and I set out a framework for thinking through what can be done, and how you can randomize aspects of the migration decision without randomizing migration policies. Note that this framework can be used to both think through how one can spur more migration, as well as interventions that might deter dangerous and irregular migration (as in this work I previously discussed in the Gambia).

Aspects of the migration decision

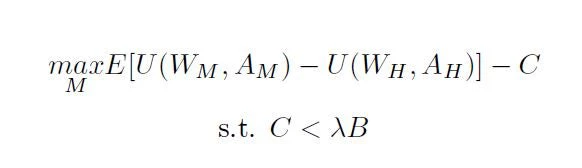

Consider a potential migrant deciding between staying in their home country where they earn home wages WH and benefitting from amenities AH, or paying a cost C to go to another destination (either abroad or in a higher paying destination internally), where they face uncertain wages WM and amenities AM. Then migration will occur if the expected gain in utility from migrating exceeds the costs of migrating, and they can afford the costs of migrating. That is, the decision is migrate if:

Where B is wealth, and λ is how tightly liquidity constraints bind.

This framework then gives a whole range of areas where interventions could be done:

1. Change the costs of migrating: these are both the monetary costs and the bureaucratic costs. For example, Hainmueller et al. lower the cost of naturalizing by giving vouchers to cover the naturalization fee; Beam et al. cover the costs of getting a passport and help with the logistics.

2. Change the ability of individuals to pay these costs – either by increasing their wealth (several studies have looked at how CCTs have funded migration), or by changing access to credit and hence how tightly the borrowing constraint binds. For example, Bryan et al. offered internal migrants in Bangladesh a loan they could use to pay the costs of migrating. There has been much less research/innovation on how to design good loan instruments for funding the much more expensive international migration. The NGO Malengo is trying this for educational migration, but I see this as an area ripe for much more experimentation.

3. Change how expectations are formed: Hidden in the E term above is that migration decisions depend on the information and beliefs potential migrants have about the wages and amenities abroad – which can often be inaccurate. For example, Shrestha gave Nepalese migrants information about wages and mortality risks at destination, and Baseler gave rural Kenyans more accurate information about earnings in urban areas. These information interventions are particularly popular in attempts to deter irregular migration by telling people about how dangerous the conditions are. However, in practice even if beliefs are biased and information is incomplete, this may not make a practical difference in many cases: e.g. I thought I could earn 5 times my current wage abroad, and in fact it is only 3 times – but its still a lot more. See this post for things to consider in implementing information interventions.

4. Change the risk and uncertainty involved: The E(U) term also recognizes that migration is a risky endeavor, and so risk preferences and uncertainty come into play. This suggests the scope for experiments that provide insurance against this risk – something which is underexplored. The one area where it has come up is with loans bundled with insurance – so you may have to repay less if you don’t earn as much after migrating. But there is definitely room for more innovation here. In addition, interventions to alleviate some of the uncertainty that comes up when considering life in a new place could help, as discussed here.

5. Change the wages and amenities at either home or abroad: For example, linking migrants to better labor intermediaries or job opportunities at destination can increase the wages (and perhaps improve the working conditions) they receive, as attempted in Bazzi et al. Amenities here can include both physical amenities (housing conditions can be a key one), as well as the presence of friends and family that increase the utility of living in one place versus another. So one could consider interventions that help potential migrants more quickly find housing, as well as connecting them to groups that provide social activities and opportunities for friendship. Efforts to reduce irregular migration often attempt to address the “root causes” of migration, which can be seen as trying to improve wages and living conditions at home. Easier said than done, since this takes us back to all of the other development interventions we work on. But as one example, Qiu et al. show how improving housing conditions in rural China reduces the propensity for internal migration.

This framework shows that there are many potential areas for interventions that do not require a law change – and where experimentation and innovation are needed. Currently there is not much (if anything) from the above that one can point to and tell a donor “you should put your money in X, it has really high success rates at improving livelihoods through migration” – but (says the researcher) there are potentially high returns from more experimentation on efforts to try different approaches. Doing so involves several logistical and methodological challenges, and our handbook chapter also provides some advice on those.

Join the Conversation