Mexico

Mexico

How has COVID-19 impacted the labor market outcomes for youth in Mexico? Can formal employment offer protections for vulnerable youth going through economic shocks?

These are questions that we’re trying to answer using data from an ongoing labor market inclusion pilot study in San Luis Potosi, Mexico, which targets low-income youth (between 18-21 years old) who recently graduated from upper secondary education. The study tests a program of wage subsidies to improve access and permanence in formal jobs for youth. Since June 2019, we have been tracking about 2,000 youths’ labor status through SMS surveys every two to four weeks. In April 2020, we introduced specific questions to monitor the effects of the COVID-19.

Here are three insights we’ve uncovered so far.

Partial lockdown measures affected everyone, but particularly young women

Hours worked decreased sharply in the first two months of lockdown from an average of 8 hours per day in March 2020 to 6 hours per day for males and 5 hours per day for females in April 2020. Hours showed signs of recovery in June when lockdown measures were relaxed.

Most young workers reported that their firms implemented furloughs during the first months of lockdown, while only a few were able to work from home. Firms also cut benefits or forced workers to use vacation days. Most respondents reported lower earnings as a consequence of lockdown measures, however, this seems to have affected women more than men.

Table 1. Strategies implemented by firms to cope with the COVID-19 crisis

|

|

April 2020 |

|

June 2020 |

||

|

|

Males |

Females |

|

Males |

Females |

| Hours worked |

6 |

5 |

|

8 |

7 |

| Remote work |

20% |

36% |

|

18% |

21% |

| Lower earnings |

54% |

60% |

|

44% |

55% |

| Firm declared technical shutdown |

56% |

58% |

|

23% |

26% |

| Firm cut worker’s benefits |

34% |

36% |

|

28% |

34% |

| Firm used worker’s vacation days |

27% |

35% |

|

13% |

13% |

Low-income youth holding formal jobs fared better than youth holding informal jobs

Both informal and formal workers were affected by reductions in their earnings, but earnings appear to have dropped more for those with an informal job. Forty-five percent of youth with informal jobs who reported lower earnings actually received no income at all between April and June, compared to 18 percent of their counterparts with formal jobs. Between April and May, when lockdown measures were at a peak, youth with formal jobs worked around 1.5 fewer hours than their peers with an informal job, suggesting lower compliance with the lockdown among informal workers. It also suggests that formal workers can afford to work less, while informal workers must continue working to make ends meet. After lockdown measures were relaxed in June, youth in formal jobs returned to work 8 hours per day (pre-crisis levels), while those in informal jobs worked one hour less.

Respondents with a formal job were also 12 percentage points less likely than informal workers to report having a supplementary economic activity (e.g. selling food or products, offering a service, or working for the family business) to support the loss of income at the household level during the pandemic. Respondents with formal jobs reported being 11 percentage points more optimistic about keeping their jobs in the next month compared to informal workers.

Wage subsidies paid directly to low-income youth might be a promising incentive to lead them to formal jobs

We have been testing a monthly wage subsidy of approximately USD $40 for up to six months to youth who recently graduated from upper-secondary education in Mexico. We offered the subsidy to about 1,000 youth, on the condition that they find and keep a formal job. Based on consultations with firms, our hypothesis is that if the worker can maintain the job for six months, they will gain valuable employment skills and potential wage increases. To measure how effective the subsidy is, we also created a control group of about 1,000 youth who were not offered payment. The experiment has been ongoing since June 2019.

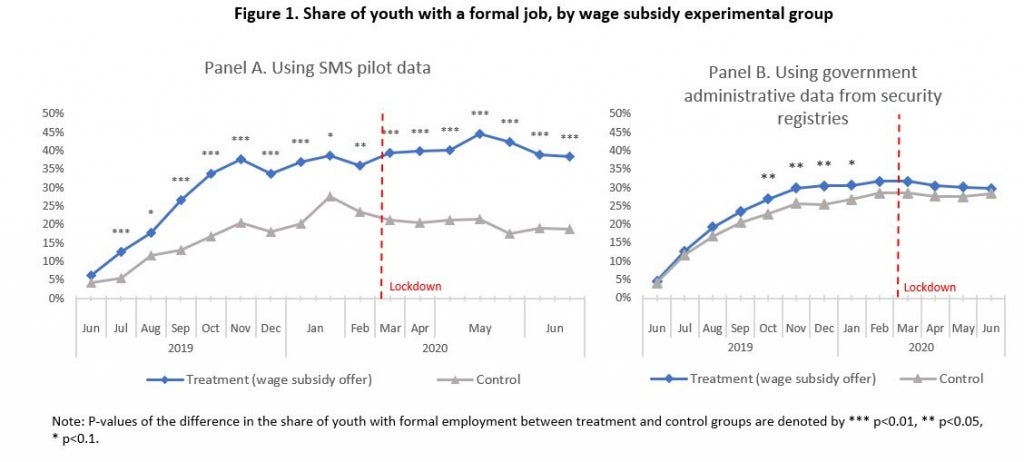

Our preliminary findings show that youth who were offered a subsidy were between 3.3 and 15 percentage points more likely to find and keep a formal job, compared to youth who did not receive the offer (see Fig. 1). This effect appears to be stronger for males, youth from vocational and mixed-track schools, youth who planned to work after upper-secondary school, and youth with middle- to high-levels of socioeconomic vulnerability.

Youth who were offered a subsidy also were 31.4 percent more likely to be formally employed with a permanent contract, as opposed to a temporary contract. That has been sustained over time, even after lockdown measures were introduced, suggesting that a wage incentive that speeds up rates of formal employment may help protect youth from economic shocks .

Join the Conversation