Mwajuma* was 15 in rural Shinyanga when her parents informed her she would not be going to school anymore – she was getting married. She never objected. Several of her peers had similarly had their schooling terminated and were already busy taking care of their own families. Neither did she object to the fact she was to be the second wife – this too was commonplace among her peers. But the marriage did not last.

At 23, Mwajuma is a domestic worker in Dar es Salaam where she fled to when the marriage became unbearable. She hopes to be able to save enough money and reunite with her two children, a son aged six, and a daughter, four, who currently live with her husband’s mother.

“Even though I never got the chance, my goal is to make sure my children complete their education and not end up like me,” Mwajuma said.

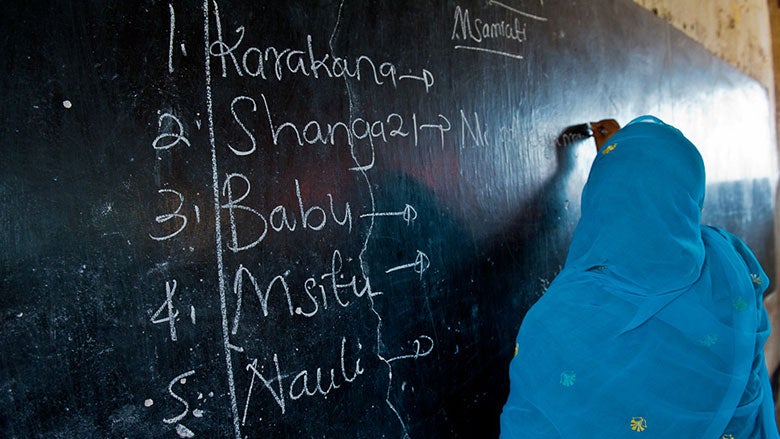

Mwajuma’s story is not unusual in Tanzania. Almost one in three girls marry before they reach the age of 18. Almost one in four have their first child before the age of 18. Partly as a result of this, just over one in four girls completes her secondary education.

Progress has been made over the last few decades in ending child marriage and increasing access to education for both girls and boys. Government initiatives such as the Fee-Free Basic Education Policy should help improve outcomes for girls. Yet the rate of progress towards reducing child marriage and improving educational attainment at the secondary level is too slow to enable Tanzania to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Compared to other East and Southern African countries, adolescent girls in Tanzania continue to fare poorly. Much more can be done to unleash the benefits from investing in girls.

The 11th Tanzania Economic Update shows that girls’ educational attainment, child marriage, and early childbearing are all closely related. Once a girl is married, it is very difficult for her to remain in school. Indeed, less than 1% of girls aged 15-19 are both in school and married. Conversely, keeping girls in school is probably the best way to reduce child marriage and, indirectly, early childbearing, since child marriage is the likely cause of about two thirds of all instances of early childbearing. Ending child marriage and achieving universal secondary completion for girls could reduce fertility rates nationally by more than one fourth, thereby contributing to reducing population growth and improving standards of living through a higher gross domestic product per capita.

Girls’ education, child marriage, and early childbearing have significant impacts on a wide range of other development outcomes. Limited education and early marriage and pregnancy can affect girls’ life trajectories in many ways, leading to health challenges, larger families, and lower earnings as adults. Data shows that because the girls marry so young and lack education, they also suffer a higher risk of intimate partner violence and lack decision-making power within their household. This can negatively impact their children; estimates show that after controlling for other factors affecting under-five stunting, children of teenage mothers in Tanzania are at higher risk.

The economic benefits of ending early child marriage would be high, both to girls and wider society. The update shows that ending child marriage could generate $5 billion annually in purchasing power parity within 15 years by reducing fertility rates and population growth. In addition, the loss in earnings for adult women working today due to their marrying as children in the past stands at more than $600 million.

Ending child marriage and keeping girls in schools would require investments in improving access to education and health services as well as the quality of these services. But in the future, it could save money for governments as the reduction in population growth alleviates the pressures on basic services (such as health and education) for large cohorts of new children and students. Budget savings from lower population growth could be reinvested to improve the quality of services, enhancing human capital and generating additional economic benefits that are critical for Tanzania to reach middle income status.

The drivers of child marriage, early childbearing, and low educational attainment for girls are complex, and have been documented in a recent government study. Poverty, social norms, and gender inequality all play a role. But Tanzania has proven in the past that it can make tremendous progress in ending traditional harmful practices. This has been the case with female genital mutilation. It can also be done with child marriage.

Investing in adolescent girls by ending child marriage and educating girls is one of the best investments that Tanzania can make for its long-term sustainable development. A top priority should be to enable all girls to stay in school and complete their secondary education. In addition, imparting adolescent girls with the life skills they need would empower them throughout their adult life, and ensure benefits for future generations.

*Name has been changed.

Join the Conversation