Gas flaring, the burning of natural gas associated with oil extraction, has persisted since the beginning of oil production, some 160 years ago. It takes place due to a range of issues, from market and economic constraints, to a lack of appropriate regulation and political will, and results in substantial carbon dioxide, methane and black carbon (soot) emissions. Eliminating this practice from oil production is the very least oil and gas operators can do to limit their direct emissions and will help countries achieve their Paris Agreement goals, advancing their path to decarbonization and renewable energy sources. Indeed, if all flaring was eliminated, it would reduce CO2 equivalent emissions by 400 million tons each year.

For many years the World Bank’s Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership (GGFR) has ranked the top gas flaring countries in the world by volumes flared and by volumes flared per barrel of oil produced (flaring intensity). However, we have not looked at gas flaring from the oil importer or consumer perspective. With climate action a central focus of many governments and a growing global commitment to “build back better” in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis, this is an opportune moment to bring oil-importing countries into the global discussion about ending routine gas flaring.

The burden of responsibility to reduce flaring should be shared with countries that import oil, particularly when international agreements and national commitments on climate mitigation incentivize countries to reduce emissions throughout the life cycle. Recognizing this, GGFR created a new metric, the Imported Flare Gas (IFG) Index, which communicates how countries that import crude oil are exposed to gas flaring, a critical climate and resource management issue. The IFG Index quantifies the concept that when a country imports crude oil from another country, it is also importing the flaring intensity of the producing country in proportion to the amount of crude oil imported.

This new consumer-oriented index should help oil-importing countries recognize that as importers they have an influential role in decarbonizing energy systems globally. The IFG Index can also help oil-importing countries identify “flaring hotspots” in their supply chain, where they are most exposed to flaring among the many countries from which they import oil; engage in a dialogue with countries from which they buy oil; assist producing countries in implementing flaring reduction initiatives; and improve the carbon intensity of the oil they consume.

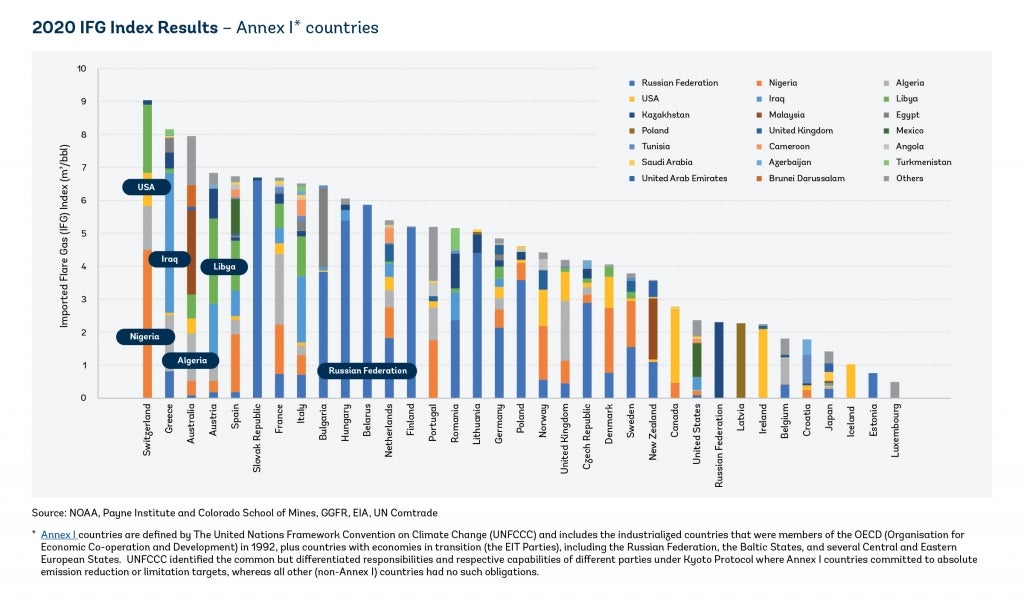

Preliminary results show that among the Annex I countries importing the greatest quantities of crude oil, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Germany have a high IFG index because they are major importers of crude oil from countries that have high gas flaring intensities, such as Algeria, Iraq, Libya, Nigeria, and Russia. These importing countries should shoulder some of the responsibility in the gas flaring reduction efforts of their oil-producing partner countries. But many other countries also share the “gas flaring burden”: Switzerland, Greece, Australia, and Austria rank highest in the index of Annex I countries, irrespective of the amount of crude oil imported, as compared to the international average. This means that these countries may import relatively less crude oil, but what they do import is from oil-producing countries with high flaring intensities. Although the European Union accounted for only 0.17 percent of global gas flaring in 2020, its members can leverage their buying power to influence suppliers and producers, catalyzing gas flaring reduction efforts.

This graph presents the Imported Flare Gas Index for all large crude importing countries. The horizontal line represents international average flaring intensity and the vertical line represents a mark of 1 million barrels per day of oil import. Those countries that appear in the top-right quadrant are countries that have a high intensity and high import: they import more than a million barrels of crude oil per day and have a higher than average imported flare intensity.

This chart shows preliminary results of this analysis – a ranking of Annex I countries in terms of their imported flare intensity – with Switzerland, Greece, Australia, Austria, and Spain among the highest and Japan, Iceland, Estonia, and Luxembourg among the lowest. Looking at the breakdown of where most of this intensity is imported from, it is clear that countries with the higher IFG Index are importing a lot of crude oil from high flaring countries, such as Algeria, Iraq, Libya, Nigeria, and Russia.

Methodology:

The IFG index is based on a simple approach that incorporates two data sets available – one is the producer’s flaring intensity from GGFR satellite data and the other is crude oil import data from Comtrade. The methodology to calculate the IFG index may be described by the following formula(s):

It has been over five years since the World Bank launched the “Zero Routine Flaring by 2030” initiative, which commits governments and oil companies that endorse the initiative not to routinely flare gas in any new oil field developments and to end routine flaring at their existing oil production sites as soon as possible and no later than 2030. Although global commitments to the initiative now represent almost two-thirds of global gas flaring, and while the World Bank and GGFR have helped governments advance gas flaring reduction programs in several of the highest gas flaring countries, shared responsibility is needed to achieve this goal. While the world transitions to a low-carbon economy, oil and gas will likely remain a significant source of energy for many countries over the next several years. We need producers and consumers to work together if we are to decarbonize the sector. Oil-producing countries should rightfully assume the lion’s share of responsibility for ending routine flaring, but oil-importing countries also have an important part to play.

In the lead-up to the next UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, governments can encourage oil-producing countries to embed gas flaring reduction in their climate action plans, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and energy policies and regulations, kickstarting crucial investments in flaring reduction projects. As we race to realize a low-carbon world, let’s work together to get some meaningful climate wins under our belts now.

Join the Conversation