The billions spent on the militarisation of border controls over the past years have been a waste of taxpayers' money. As we are able to witness during the current 'refugee crisis', increasing border controls have not stopped asylum seekers and other migrants from crossing borders. As experience and research has made abundantly clear, they have mainly (1) diverted migration to other crossing points, (2) made migrants more dependent on smuggling, and (3) increased the costs and risks of crossing borders.

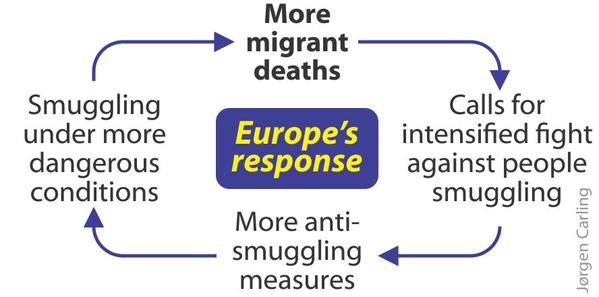

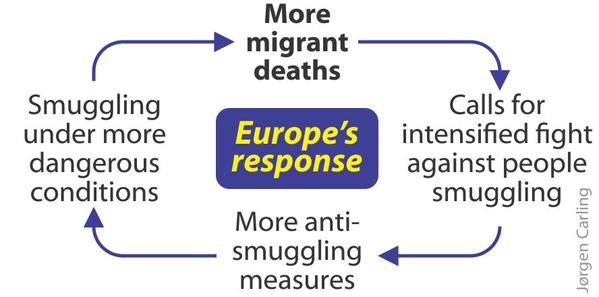

The fact is that 25 years of militarising border controls in Europe have only worsened the problems they proclaim to prevent. As a very useful graph (see below) drawn by the prominent migration researcher Jørgen Carling illustrates, the EU has been caught up in a vicious circle in which increasing number of border deaths lead to calls to 'combat' smuggling and increase border patrolling, which forces refugees and other migrants to use more dangerous routes using smugglers' services. Longer and more dangerous routes means more people who get injured or die while crossing borders, which then leads to public outrage and calls for even more stringent border controls.

In the current panic about the issue, it is often forgotten that so-called 'boat migration' across the Mediterranean is a 25-year old phenomenon that started when Spain and Italy introduced (Schengen) visas for North Africans. Before that, Moroccans, Algerians and Tunisians could travel freely back and forth to work or go on holiday. And so they did in significant numbers. However, this migration was largely circular. Most migrants and visitors would go back after a while, to be close to family and friends, because life back home is less expensive, and because they could easily re-migrate. This experience exemplifies that open migration doors tend to be revolving doors.

With the introduction of Schengen visas in 1991, free entry into Spain and Italy was blocked, and North Africans who could not obtain visas started to cross the Mediterranean illegally in pateras, small fisher boats. This was initially a small-scale, relatively innocent operation run by local fishermen. When Spain started to install sophisticated, quasi-miltary border control systems along the Strait of Gibraltar, smuggling professionalised and migrants started to fan out over an increasingly diverse array of crossing points on the long Mediterranean and Atlantic coastlines. The diversification of crossing points continued over the 2000s, in which migrants started to cross not only from Morocco and Tunisia, but also Algeria, Libya to Italy and Spain, and from the West African coast towards the Canary Islands.

While in the 1990s most people crossing were young Moroccans, Algerians and Tunisians attracted by employment opportunities in southern Europe, over the 2000s an increasing number of sub-Saharan migrants and refugees have joined this boat migration. The major upsurge in numbers over the last few years is mainly the result of an increasing number of Syrians joining this trans-Mediterranean boat migration. Over 2014 and 2015, increased maritime border patrolling in the Mediterranean is one of the causes (alongside the worsening of conditions in Syria and neighbouring countries) of the reorientation of migration routes towards Turkey, the Balkans and Central Europe.

So, these policies have been completely self-defeating. While politicians and the media routine blame 'smugglers' for the suffering and dying at Europe's borders, this diverts the attention away from the fact that smuggling is a reaction to the militarisation of border controls, not the cause of irregular migration. Ironically, policies to 'combat' smuggling and irregular migration are bound to fail because they are among the very causes of the phenomenon they claim to 'fight'.

It is therefore nonsense to blame smugglers for irregular migration and the suffering of migrants and refugees. This diverts the attention away from the structural causes of this phenomenon, and the governments' responsibility in creating conditions under which smuggling can thrive in the first place. Smugglers basically run a business, a need for which has been created by the militarisation of border controls, and migrants use their services in order to cross borders without getting caught. Of course, in the media stories abound of smugglers deceiving migrants, and such stories are certainly true, but there is good research (for instance by Ilse van Liempt and Julien Brachet) showing that smugglers are basically service providers who have an interest of staying in business and therefore generally care about their reputation and have an interest in delivering.

Certainly, smugglers can be ruthless and regularly deceive migrants, but it should not be forgotten that smugglers deliver a service asylum seekers and migrants are willing to pay for. Without smugglers, it is likely that many more people would have died crossing borders. For many refugees and migrants, smugglers are a necessary evil. For some, smugglers can be heroes. For instance, Al Jazeera quoted African refugees in Sudan who saw smugglers as freedom facilitators, because they enabled their escape toward safer countries. The irony is that European countries have created huge market for the smuggling business by multi-billion investments of taxpayers' money in border controls. There is no end to this cat-and-mouse game, in which smugglers constantly adapt their itineraries and smuggling techniques.

So don't blame the smugglers. Blaming smugglers also diverts the attention away from the vested interests of the military-industrial complex involved in border controls. Under influence of the growing panic about irregular migration and the perception that (supposedly uncontrolled) migration is an imminent threat to Western societies, states have invested massive amounts of taxpayers' money in border surveillance. Border controlling have become a huge industry, and businesses involved in building fences and walls, electronic border surveillance systems, patrolling vessels and vehicles as well as the military have a vested interest in making the public believe that we are facing an impending migration invasion and that we therefore need to 'fight' smugglers, as if we are indeed waging a war.

This reveals the contours of the real migration industry. Arms and technology companies have reaped the main windfalls from Europe’s delusional 'fight against irregular migration'. As has been documented by the Migrant Files, four leading European arms manufacturers (Airbus (formerly EADS), Thales, Finmeccanica and BAE) and technology firms like Saab, Indra, Siemens and Diehl are among the prime beneficiaries of EU spending on military-grade technology supplied by these privately held companies whose R&D programs have been financed by EU subsidies. The staging of uncontrolled migration as an essential threat to Western society has also served the military, who were in search of a raison d'être after the Communist threat evaporated with the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In this way, Europe's immigration policies have created a huge market for the private companies implementing these policies as well as smugglers. The main victims are migrants and refugees themselves, through soaring smuggler fees and an increasing death tolls. But also European taxpayers who have been deceived and lured into a delusional 'fight against illegal migration' by fear-mongering nationalistic politicians. While the same politicians fan the flames of xenophobia by insinuating that refugees will be a huge drain on public funds and a threat to social cohesion, they waste billions of public funds on border controls, which have not stopped irregular migration, but created a market for smuggling and increased the suffering and death toll at Europe's borders - at least 30,000 people died in their attempt to reach or stay in Europe since 2000.

This has created a multi-billion industry, which has huge commercial interest in making the public believe that migration is an essential threat and that border controls will somehow solve this threat. According to a series of investigations by the Migrant Files, since 2000 refugees and migrants spend over €1 billion a year to smugglers to reach Europe. European countries pay a similar amount of taxpayer money to keep them out, a few companies and smugglers benefiting in the process. Since 2000, the 28 EU member states plus Norway, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and Iceland have deported millions of people, with a price tag of least 11.3 billion euro. A further billion has been spent on coordination efforts to control European borders, mainly through Frontex, Europe's border agency. The real costs are much higher, as these figures do not include expenditures on regular border controls by individual member states.

Across the Atlantic, similar same dynamics can be found on the US-Mexican border, where soaring public expenditure on border controls has fuelled a military-industrial complex consisting of arms manufacturers, technology firms, (privatized) migrant detention centres, the military and state bureaucracies involved in deporting people. In a study entitled Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery, published in 2013, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), a Washington-based migration think tank, calculated that the US government spent $187 Billion on Federal Immigration Enforcement between 1986 and 2012.

To put this in perspective, the same report showed that $18 billion spent in 2012 are 24% higher, then the combined costs on all other principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies (FBI, Drug Enforcement Administration, Secret Service, U.S. Marshals Service and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives). While these costs are staggering, they have created a huge parallel market for smugglers ( coyotes) helping migrants from Mexico and, increasingly, Middle America, to defy border controls.

So, instead of blaming smugglers, it is important to be aware governments have in many ways created their own monster by pouring massive public funds in the migration control industry. Like the mythological Hydra of Lerna, for which each head lost was replaced by two more, each time a migration route is blocked such as through erecting a fence, it will create an ever expanding market for smugglers helping people to get over, under or around migration barriers. This has led to an unintended increase in the area that countries have to monitor to ‘combat’ irregular migration to span the entire European external border, making the phenomenon less, instead of more, controllable.

National politicians arguing that border controls can solve the current 'refugee crisis' are thus selling illusions. The current situation in the Balkans and Central Europe makes this abundantly clear. As long as violent conflict persists in countries like Syria, as well as labour demand for undocumented migrant workers, people will keep on coming, in one way or another.

There is no easy 'solution' to this problem, but it should be clear that the solutions of the past have been a counterproductive waste of money and have cause unspeakable suffering. Notwithstanding its limitations, the agreement reached on 22 September by the European Union member states to share responsibility by spreading refugees over Europe, is hopefully a first sign that the public and governments have finally come to realise that, public funds are better spent on providing concrete support and access to refugee status determination procedures to asylum seekers as well as supporting the countries hosting largest numbers of refugees (such as Turkey, Syria and Jordan).

Although many obstacles are still in the way of reaching a truly European immigration and refugee policy, this hopefully sets an important precedent towards real solutions, away from the delusional politics of wasting taxpayers money on the militarisation of borders.

This blog was first posted on heindehaas.blogspot.com on September 23, 2015 ( original blog post ).

The fact is that 25 years of militarising border controls in Europe have only worsened the problems they proclaim to prevent. As a very useful graph (see below) drawn by the prominent migration researcher Jørgen Carling illustrates, the EU has been caught up in a vicious circle in which increasing number of border deaths lead to calls to 'combat' smuggling and increase border patrolling, which forces refugees and other migrants to use more dangerous routes using smugglers' services. Longer and more dangerous routes means more people who get injured or die while crossing borders, which then leads to public outrage and calls for even more stringent border controls.

Source/author:

Jo

rgen Carling

In the current panic about the issue, it is often forgotten that so-called 'boat migration' across the Mediterranean is a 25-year old phenomenon that started when Spain and Italy introduced (Schengen) visas for North Africans. Before that, Moroccans, Algerians and Tunisians could travel freely back and forth to work or go on holiday. And so they did in significant numbers. However, this migration was largely circular. Most migrants and visitors would go back after a while, to be close to family and friends, because life back home is less expensive, and because they could easily re-migrate. This experience exemplifies that open migration doors tend to be revolving doors.

With the introduction of Schengen visas in 1991, free entry into Spain and Italy was blocked, and North Africans who could not obtain visas started to cross the Mediterranean illegally in pateras, small fisher boats. This was initially a small-scale, relatively innocent operation run by local fishermen. When Spain started to install sophisticated, quasi-miltary border control systems along the Strait of Gibraltar, smuggling professionalised and migrants started to fan out over an increasingly diverse array of crossing points on the long Mediterranean and Atlantic coastlines. The diversification of crossing points continued over the 2000s, in which migrants started to cross not only from Morocco and Tunisia, but also Algeria, Libya to Italy and Spain, and from the West African coast towards the Canary Islands.

While in the 1990s most people crossing were young Moroccans, Algerians and Tunisians attracted by employment opportunities in southern Europe, over the 2000s an increasing number of sub-Saharan migrants and refugees have joined this boat migration. The major upsurge in numbers over the last few years is mainly the result of an increasing number of Syrians joining this trans-Mediterranean boat migration. Over 2014 and 2015, increased maritime border patrolling in the Mediterranean is one of the causes (alongside the worsening of conditions in Syria and neighbouring countries) of the reorientation of migration routes towards Turkey, the Balkans and Central Europe.

So, these policies have been completely self-defeating. While politicians and the media routine blame 'smugglers' for the suffering and dying at Europe's borders, this diverts the attention away from the fact that smuggling is a reaction to the militarisation of border controls, not the cause of irregular migration. Ironically, policies to 'combat' smuggling and irregular migration are bound to fail because they are among the very causes of the phenomenon they claim to 'fight'.

It is therefore nonsense to blame smugglers for irregular migration and the suffering of migrants and refugees. This diverts the attention away from the structural causes of this phenomenon, and the governments' responsibility in creating conditions under which smuggling can thrive in the first place. Smugglers basically run a business, a need for which has been created by the militarisation of border controls, and migrants use their services in order to cross borders without getting caught. Of course, in the media stories abound of smugglers deceiving migrants, and such stories are certainly true, but there is good research (for instance by Ilse van Liempt and Julien Brachet) showing that smugglers are basically service providers who have an interest of staying in business and therefore generally care about their reputation and have an interest in delivering.

Certainly, smugglers can be ruthless and regularly deceive migrants, but it should not be forgotten that smugglers deliver a service asylum seekers and migrants are willing to pay for. Without smugglers, it is likely that many more people would have died crossing borders. For many refugees and migrants, smugglers are a necessary evil. For some, smugglers can be heroes. For instance, Al Jazeera quoted African refugees in Sudan who saw smugglers as freedom facilitators, because they enabled their escape toward safer countries. The irony is that European countries have created huge market for the smuggling business by multi-billion investments of taxpayers' money in border controls. There is no end to this cat-and-mouse game, in which smugglers constantly adapt their itineraries and smuggling techniques.

So don't blame the smugglers. Blaming smugglers also diverts the attention away from the vested interests of the military-industrial complex involved in border controls. Under influence of the growing panic about irregular migration and the perception that (supposedly uncontrolled) migration is an imminent threat to Western societies, states have invested massive amounts of taxpayers' money in border surveillance. Border controlling have become a huge industry, and businesses involved in building fences and walls, electronic border surveillance systems, patrolling vessels and vehicles as well as the military have a vested interest in making the public believe that we are facing an impending migration invasion and that we therefore need to 'fight' smugglers, as if we are indeed waging a war.

This reveals the contours of the real migration industry. Arms and technology companies have reaped the main windfalls from Europe’s delusional 'fight against irregular migration'. As has been documented by the Migrant Files, four leading European arms manufacturers (Airbus (formerly EADS), Thales, Finmeccanica and BAE) and technology firms like Saab, Indra, Siemens and Diehl are among the prime beneficiaries of EU spending on military-grade technology supplied by these privately held companies whose R&D programs have been financed by EU subsidies. The staging of uncontrolled migration as an essential threat to Western society has also served the military, who were in search of a raison d'être after the Communist threat evaporated with the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In this way, Europe's immigration policies have created a huge market for the private companies implementing these policies as well as smugglers. The main victims are migrants and refugees themselves, through soaring smuggler fees and an increasing death tolls. But also European taxpayers who have been deceived and lured into a delusional 'fight against illegal migration' by fear-mongering nationalistic politicians. While the same politicians fan the flames of xenophobia by insinuating that refugees will be a huge drain on public funds and a threat to social cohesion, they waste billions of public funds on border controls, which have not stopped irregular migration, but created a market for smuggling and increased the suffering and death toll at Europe's borders - at least 30,000 people died in their attempt to reach or stay in Europe since 2000.

This has created a multi-billion industry, which has huge commercial interest in making the public believe that migration is an essential threat and that border controls will somehow solve this threat. According to a series of investigations by the Migrant Files, since 2000 refugees and migrants spend over €1 billion a year to smugglers to reach Europe. European countries pay a similar amount of taxpayer money to keep them out, a few companies and smugglers benefiting in the process. Since 2000, the 28 EU member states plus Norway, Liechtenstein, Switzerland and Iceland have deported millions of people, with a price tag of least 11.3 billion euro. A further billion has been spent on coordination efforts to control European borders, mainly through Frontex, Europe's border agency. The real costs are much higher, as these figures do not include expenditures on regular border controls by individual member states.

Across the Atlantic, similar same dynamics can be found on the US-Mexican border, where soaring public expenditure on border controls has fuelled a military-industrial complex consisting of arms manufacturers, technology firms, (privatized) migrant detention centres, the military and state bureaucracies involved in deporting people. In a study entitled Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery, published in 2013, the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), a Washington-based migration think tank, calculated that the US government spent $187 Billion on Federal Immigration Enforcement between 1986 and 2012.

To put this in perspective, the same report showed that $18 billion spent in 2012 are 24% higher, then the combined costs on all other principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies (FBI, Drug Enforcement Administration, Secret Service, U.S. Marshals Service and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives). While these costs are staggering, they have created a huge parallel market for smugglers ( coyotes) helping migrants from Mexico and, increasingly, Middle America, to defy border controls.

So, instead of blaming smugglers, it is important to be aware governments have in many ways created their own monster by pouring massive public funds in the migration control industry. Like the mythological Hydra of Lerna, for which each head lost was replaced by two more, each time a migration route is blocked such as through erecting a fence, it will create an ever expanding market for smugglers helping people to get over, under or around migration barriers. This has led to an unintended increase in the area that countries have to monitor to ‘combat’ irregular migration to span the entire European external border, making the phenomenon less, instead of more, controllable.

National politicians arguing that border controls can solve the current 'refugee crisis' are thus selling illusions. The current situation in the Balkans and Central Europe makes this abundantly clear. As long as violent conflict persists in countries like Syria, as well as labour demand for undocumented migrant workers, people will keep on coming, in one way or another.

There is no easy 'solution' to this problem, but it should be clear that the solutions of the past have been a counterproductive waste of money and have cause unspeakable suffering. Notwithstanding its limitations, the agreement reached on 22 September by the European Union member states to share responsibility by spreading refugees over Europe, is hopefully a first sign that the public and governments have finally come to realise that, public funds are better spent on providing concrete support and access to refugee status determination procedures to asylum seekers as well as supporting the countries hosting largest numbers of refugees (such as Turkey, Syria and Jordan).

Although many obstacles are still in the way of reaching a truly European immigration and refugee policy, this hopefully sets an important precedent towards real solutions, away from the delusional politics of wasting taxpayers money on the militarisation of borders.

This blog was first posted on heindehaas.blogspot.com on September 23, 2015 ( original blog post ).

Join the Conversation