Korotoum Coulibaly and Doussou Diarra gather shea nuts in a field outside of Kodiolan, Mali.

Korotoum Coulibaly and Doussou Diarra gather shea nuts in a field outside of Kodiolan, Mali.

Evidence shows that the coronavirus is deadlier for men; however, women are facing more economic hardship. Women hold fewer of the good jobs that can be done online at home. They are over-represented in the informal sector with less access to finance. Women provide more caregiving, and too many women face risk of violence in their own homes.

Women hold vulnerable jobs

Fatimada, an onion farmer in Mauritania, recently had to give up onion farming during the peak of harvest and comply with the government’s COVID policy to stay home. She will not sell any onions this year, which means she will not be able to pay the loan on her land.

Lockdown policies hurt small-scale producers like Fatimada, leading to lost income and increased financial dependence on men. Informal workers, most of whom are women and lack access to credit and social safety nets , account for more than two-thirds of the workforce in developing countries, ranging from 60 percent in Latin America to over 90 percent in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. These women’s jobs are particularly at risk during the pandemic.

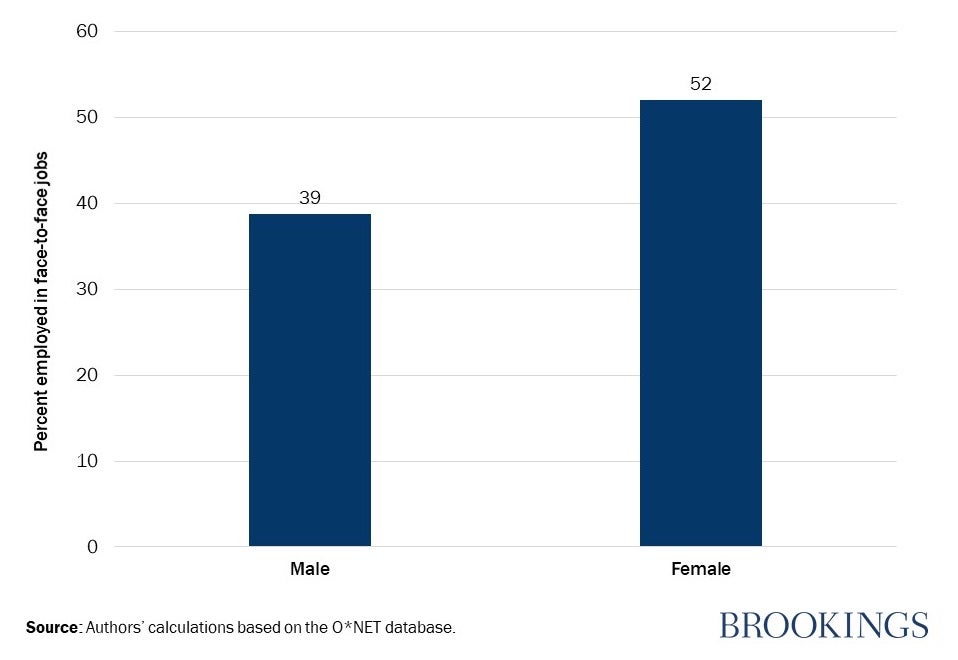

Even in the formal sector, women hold more of the jobs most at risk during the pandemic. Global data show that women hold a disproportionate share of occupations requiring face-to-face interactions, like in retail or personal care, making them less likely to work from home and prone to becoming unemployed. (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Women are more exposed to face-to-face interactions than men.

Preliminary data from countries more severely impacted by the pandemic show hardship for women. Close to 60 percent of the jobs lost in the U.S. until mid-March were held by women, while in the UK, sectors shut down as a result of social distancing measures employed 17 percent of all female employees and 13 percent of all male employees. In Spain, 90 percent of women and 64 percent of men work in the service sector, where unemployment has surged most rapidly due to the national lockdown. A recent UN study forecasts that women in the Middle East and North Africa will lose a third of total jobs in the region, while representing only a fifth of the labor force.

Women are more affected at home

Women’s caregiving responsibilities at home has also grown as the COVID-19 pandemic keeps millions of children around the world from attending school. Women bear the bulk of childcare, which negatively affects their ability to work, even if they can continue to work from home.

Violence against women is also rising, as a result of ongoing stress on families and communities. In Hubei province, the heart of the initial coronavirus outbreak, domestic violence reports to police more than tripled in one county during the lockdown in February. In Brazil a state-run drop-in center for domestic violence victims has seen a surge of almost 50 percent in cases it attributes to coronavirus isolation.

Access to finance

With little revenue coming in, firms—especially women-owned ones—are struggling with limited access to credit. Globally, 80 percent of women-owned businesses with credit needs are either unserved or underserved. In the COVID environment, banks may become even more risk averse and decrease loans to women further.

We can do better

History tells us successful economic recovery will require women’s active participation. After World War II, women joining the workforce played a significant role in rebooting the US economy and speeding up recovery. During the 1918 flu pandemic, women stepped into public roles that hadn’t previously been open to them and successfully became government, community and business leaders.

Today, many economies lack the legal and regulatory framework to support women’s economic participation, during and after the crisis. In economies where women have more bargaining power at home, equality in access to finance, protection from violence, and equality in employment opportunities in all industries and sectors, women are better equipped to weather economic shocks.

Governments should undertake policy measures to reduce the crisis’ impact on women by improving their access to economic opportunities and subsequently, their resilience. Actionable policy measures based on data from Women, Business, and the Law point in this direction.

Support women’s autonomy by improving their bargaining power at home. Introducing measures such as freedom of movement, protection from domestic violence, head of household provisions, equality in divorce and removing obedience provisions could support women’s influence in the family. Fifty-nine economies impose at least one restriction on women’s mobility and 35 countries have no domestic violence legislation. In 2019, Saudi Arabia gave women freedom of movement and the ability to be head of household, along with other pro-women measures. Subsequently, women owned businesses have increased by 50 percent.

Diversify economic opportunities for women by leveling the playing field in access to employment and across sectors and industries. Enacting laws mandating non-discrimination in employment, lifting industry restrictions on women and limitations on night work would help achieve this objective. Currently, 74 economies prohibit women from working in the same industries as men, including mining, construction, transportation among other sectors, while 36 economies do not prohibit discrimination based on gender in employment.

Support economic prospects for women by improving access to finance, equality in employment and retirement. Governments could mandate equal access to credit by men and women, mandate equal pay for work of equal value and equalize the pension rules for men and women. Over 100 economies still lack legislation mandating equal remuneration for work of equal value. In 66 economies, the ages at which men and women can retire with full pension benefits are not equal.

Reduce women’s dropout rate from the job market. The right incentives include policies to ensure women have a safe and conducive working environment, protection from sexual harassment, access to child care and leave. Seventy-five economies do not comply with the ILO’s 14-week threshold for paid maternity leave, and 85 economies have no paid leave available to fathers. Thirty-eight economies have no legislation prohibiting the dismissal of pregnant workers and 50 economies do not protect women from sexual harassment at work.

To keep track we need data

To support effective decision-making to increase economic opportunities for women, it is also critical that governments collect and share data. Important indicators include: women’s opportunities for employment, entrepreneurship, access to credit, and informality, as well as COVID-related data on jobs lost by sector, women’s dropout rate from the labor market, and the incidence of domestic violence. The availability of reliable data will support policy choices aiming to help women and the economy weather the crisis and speed up economic recovery.

Join the Conversation