So here it is… I do not believe that behavior change interventions can effect lasting change in people’s travel patterns unless real choices are available to them within the local context. My reasoning is that many of the people who live in our client countries still simply do not have a choice, for instance about how they get to work or to a health clinic, so simply deploying persuasive communication techniques will not make them change their behavior. Also, experience with environmental and health problems shows that access to factual information does not necessarily lead to changes in attitude. Instead, it may well be our work through policies and investments in transportation that should lead the way for people to change their mobility behavior.

My work in transportation regularly crosses the path of the research and evidence from the health sector, which has developed tools for influencing behavior change: public information is available on nutritional aspects of food to purchase; warning labels point out the dangers of cigarettes; and commercials demonstrate the perils of unsafe driving. While these tools have raised awareness on these important health issues, some of their impact on behavior change is still being debated.

Take the growing epidemic of obesity in developing countries as another example. Once restricted to the rich industrialized nations, high-fat diets and Western eating habits are now increasingly entering the diet of low-income countries and fostering new nutrition problems. The problems of inappropriate diets cannot be solved only through the provision of advice on good nutrition, however effective and persuasive. Without access to healthy food choices with less sugar and high fat, individuals cannot make positive changes to their diets.

In transportation, promoting behavior change in the way people travel and identifying the right incentives for change is also challenging. Fuel, parking and car taxes have worked to limit the expansion of driving but have not necessarily fostered behavior change in the way people move around. A recent article by the Economist on the ‘Future of driving’ offers some interesting explanations about recent behavior change that is taking place in mobility patterns linked to car driving in OECD countries (http://www.economist.com/node/21563280 ). Cars have been an integral part of modern life in these countries but their ownership and use (in terms of vehicles- km travelled) have recently started declining. In addition to economic factors linked to this trend, it is argued that the increased provision of sustainable mass transit alternatives, shared car ride systems and stronger interest in inner city living, which limits the traditional burdens imposed by geography and distance, have contributed to this behavior change.

A key question for developing countries about behavior change and transportation is linked to driving due to the current challenges caused by rapid motorization, increased traffic and road construction taking place in many of these countries. There is also related congestion, high levels of road traffic injuries, and high concentrations of air pollutants (lead, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, etc.) in the atmosphere, with serious respiratory and other health effects for the population, particularly in urban areas. In these economies, change in travel pattern is not yet driven by choice and information about health implications or the environment. Change is driven by the urgent need to meet the growing demand for mobility on cities’ infrastructure and roads.

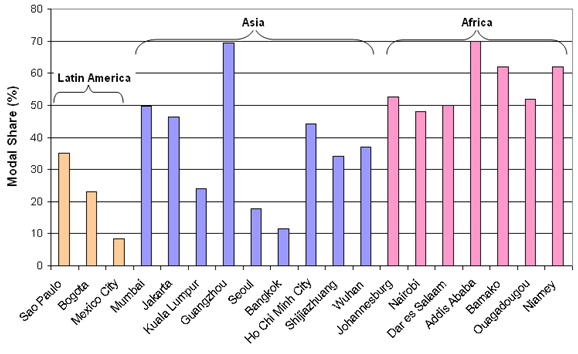

Knowing about the existing transportation choices in developing countries should be a first step in addressing these urgent challenges. For example, walking is often the only option available and the main link in the travel chain to any other mode of transport. Between 25 and 50 percent of trips in the major Indian cities and around 50 percent of all trips in major African cities are entirely on foot, and trips undertaken primarily by public transport also involve significant walking distances (http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTTRANSPORT/Resources/tp-18-walk-urban.pdf ). Yet, pedestrian space is continually being eroded or frequently occupied by street vendors, encroached upon by shop premises, or blocked by parked cars, motorcycles, and bicycles.

Walking modal share in select developing cities

Source: UITP Millennium Cities Database, SSATP Working Paper No. 80. and Urban Poverty and Transport: The Case of Mumbai.

Similarly, informal transport services and non-motorized forms of transport often provide alternative choices of transport for vulnerable and excluded groups who may be living in crowded slums within cities or in more remote peri-urban areas with limited access to jobs and social services. These alternatives modes are used because they tend to be less expensive, more flexible in routing, faster and more reliable than more formal modes of transport like cars or public buses. Displacing a transport mode that is popularly used by poor people and other vulnerable groups to make way for another that could be more polluting or dangerous should be carefully evaluated to avoid significant impact on the poor.

Developing countries now have an opportunity to influence behavior change in travel patterns through policies that offer choices in meeting the mobility needs and constraints of users in a sustainable way. This implies the consideration of travel patterns that are already conducive to safer and healthier transport options and that circumvent reliance on car driving as the easiest transportation option. The provision of a safe and accessible pedestrian environment should weigh heavily in these considerations as well as a systematic analysis of the needs and requirements of vulnerable groups, including women and people with disability, who tend to be among the poorest and seldom given importance in the planning and design phase of road infrastructure.

In this respect, two recent World Bank publications Turning the Right Corner: Ensuring Development Through a Low-carbon Transport Sector , and Inclusive Green Growth: The Pathway to Sustainable Development are excellent resources for examining policies for green growth and changing behavior for transport emissions in a way that supports more sustainable transport mobility patterns. These two publications support the argument that behavior change in developing countries will require planning and investing in infrastructure that indirectly provides choices to people.

Photo credit: Travel Aficionado

Join the Conversation