A young man places his hand on a horse’s face. Photo credit: Melusi Ndhlalambi/ World Bank

A young man places his hand on a horse’s face. Photo credit: Melusi Ndhlalambi/ World Bank

Liphula (a pseudonym to protect the privacy of the student) is a 21-year-old young man enrolled in Grade 11 at Mohlapiso High School in Qacha’s Nek district of the Kingdom of Lesotho. He attends school with only five other learners in his class because most of his peers have dropped out of school before reaching secondary education. He is the only male student in his class, a common phenomenon in Lesotho’s secondary education classrooms, where enrollment of male students is low compared to female students.

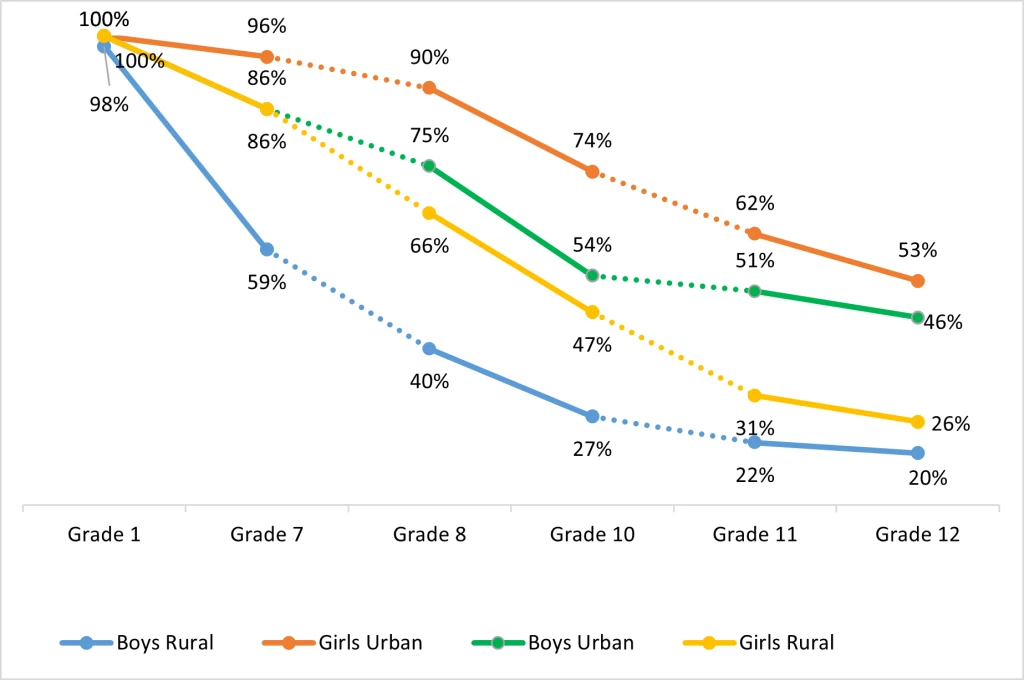

Lesotho has made encouraging progress in expanding access to primary education (Grades 1-7) by implementing a free primary education policy in 2010. However, many children drop out of school across grades, and this is especially true for boys living in rural areas. This results in low enrollment and completion rates at the secondary education level. Only one in five boys complete Grade 12 in rural areas. The figure is only slightly higher for girls in rural areas, with just over one in four girls completing Grade 12 (Figure 1). Students in urban areas perform better in terms of school enrollment and completion than those in rural areas. Yet, even within urban areas, boys’ enrollment and completion rates lag behind that of girls.

Figure 1: Enrollment profile by gender and location in Lesotho, 2018

These findings are described in detail in a recent World Bank study “The Education-Employment Paradox: A Life Cycle Approach to Assess Gender Gaps in Education and Labor Market Outcomes in Lesotho”. The study employs a life-cycle framework to assess gender inequalities in education and human capital outcomes in three different stages : early childhood (infanthood to age 5), school-age children (ages 6-17), and youth into adulthood (ages 18 and beyond).

Key findings of the study include:

- Young boys and girls start their lives facing significant disadvantages in health, nutrition, and education. Early childhood mortality rates are high, with 86 children per 1,000 births dying before reaching age five in Lesotho, worse than the averages for Sub-Saharan African countries (76 deaths per 1,000 births) and Lower Middle-Income Countries (49 deaths per 1,000 births). The stunting and underweight rates among children ages 0-5 are also high, at 35% and 10% respectively. Consequently, children face significant risks of developmental delays, diminished ability to learn, and reduced lifelong productivity. Furthermore, early childhood cognitive and socioemotional outcomes remain poor, with outcomes in early literacy and numeracy skills being particularly low. For example, a 2018 assessment of pre-primary aged children (ages 3-5) showed that, on average, children in this group were able to identify only about 1.3 letters out of the 16 letters shown to them.

- Boys underachieve compared to girls during the school years, both in terms of the number of years they stay in schools and in their learning levels. At the primary education level, while 90% of girls reach Grade 7, only 66% of boys reach the same grade and this gap widens in lower secondary education. Girls also have higher learning levels than boys in primary education. By age 10, 67% of girls compared to 40% of boys demonstrate foundational reading skills, while 27% of girls, compared to 10% of boys show foundational numeracy skills. At the secondary education level, boys and girls have comparable levels of learning. However, this equivalency may be in part due to the disproportionately high dropout rate among boys, which could lead to the better-performing boys staying on to reach secondary school. While the issue of boys’ underachievement on enrollment and learning is acute in Lesotho, we are seeing a similar pattern emerge in the southern Africa region including in South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, and Eswatini.

- Boys and girls in Lesotho face multiple constraints that affect their ability to go to school. Poverty, the demand for child labor (e.g., herding among boys), and being an orphan‒usually due to HIV/AIDS‒are all factors that drive the high level of students dropping out of school. Gender norms around masculinity, which place a strong emphasis on boys becoming “men” and taking responsibility in the household, particularly financial responsibility, put boys at a greater risk of dropping out of school to work. The dropout rate among girls is also high, albeit lower than boys, and the primary reasons cited for girls dropping out of school are poverty and pregnancy. Teenage pregnancy in Lesotho is estimated at 17.8% among 15–19-year-old girls nationally and is even higher amongst girls from poor families (25%), pointing to a linkage between poverty and adolescent pregnancy.

- Even in post-secondary education and training (PSET), women have higher levels of enrollment compared to men and account for 60% of total enrollment. However, there is significant gender segregation by field of study in PSET, with women having lower levels of participation in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields. Women account for only 26% of total enrollment in engineering, manufacturing, and construction and 37% in information and communication technology (ICT), natural sciences, mathematics, and statistics related fields.

- Still, the advantage girls and women have across the various levels of education has not fully translated into better labor market outcomes. Among working-age individuals (i.e., ages 15 or older) women’s labor force participation is only 44.8% compared to 54.7% for men. Outdated gender norms in Lesotho place the primary responsibility for childcare and housework on women and, given the scarcity of affordable and accessible childcare, mothers are often not able to stay in the labor market. Women that do enter the labor force in Lesotho are more likely to be employed in the informal sector and they earn less than men.

Moving forward, there is a need to better understand the complexity of gender disparities in Lesotho and in other countries in southern Africa and bring renewed attention to this multifaceted issue. More importantly, there is an urgent need to implement multi-sectoral solutions that address the critical challenges boys and girls face in their human capital development , while ensuring that these solutions are gender-responsive, to meet the specific and differing needs of boys and girls.

Policy and programmatic actions could be targeted toward the following areas:

- In early childhood: Expand access to early childhood services, including education, nutrition, health, and social protection, which are essential to lay a solid foundation for human capital development across the life cycle. Furthermore, shift the focus of early childhood development interventions towards whole-child learning that recognizes variability in child development, including across genders. Such investments in the early years can be a cost-effective approach for Lesotho to prevent gender disparities that emerge early and persist over the life cycle.

- During the school years: Strengthen foundational learning in primary grades, to equip boys and girls with basic literacy and numeracy skills that are crucial to all their future learning, to ensure that children do not fall behind and worse, drop out of school. At the secondary level, provide capacity-building support to teachers, both in terms of content knowledge and pedagogical skills (e.g., to meet the needs of adolescent boys and girls). Train teachers to shift harmful gender biases they may have (e.g., biases about boys being disruptive or girls being incompetent in STEM), to ensure that schools are accessible to and supportive of all children.

- Break the impact of poverty on school attendance and completion, especially at the secondary level. This will require targeted economic support to poor families to mitigate the impact of the high cost of schooling (e.g., due to school fees at the secondary level), and the high opportunity cost faced by many poor children, especially rural boys (e.g., due to demand for their labor). For Lesotho, this effort can start by strengthening the existing Orphans and Vulnerable Childrens (OVC) grant for secondary education, which needs to be better targeted to reach children from bottom wealth quintiles.

- Provide comprehensive support for adolescents through reproductive health education and services and life-skills coaching and mentorship. Such interventions have been shown to help youth make informed decisions, including about their schooling and reproductive health, as they transition into adulthood.

- Shift harmful social norms and cultural practices that perpetuate unfavorable gender roles and foster early dropout. This will require collaboration with traditional authorities such as chiefs, initiation schools, and community leaders who have a strong influence on communities and rally them to advocate for the education agenda.

- Provide alternative schooling options such as “second chance education” for children who are out of school or catch-up sessions for boys who missed class to work (e.g., so-called ‘herd boys’). Such approaches can offer the most marginalized and excluded children an alternative pathway to acquire the relevant knowledge and skills they need to become productive members of their communities.

- Youth to adulthood: Empower female youth to enter STEM fields by aggressively challenging gender biases at all levels of education, especially at upper secondary and tertiary levels where the gender gap in STEM education is the most pronounced. This requires training and advocacy among educators, educational leaders, students, and even parents, to shift entrenched biases in education at different levels and expose female students to female role models.

- Strengthen school-to-work transition support services for youth, with a strong focus on helping female youth enter fields that have been dominated by men. Interventions that provide youth with information about jobs, connections to relevant networks, provision of tailored job-matching support (e.g., through internships and targeted employment services), and help to build soft-skills needed for success in their employment can help youth successfully navigate the school-to-work transition period.

- Implement the laws and policies that are already in place to promote fairness and equity in the workplace, particularly related to equal pay for equal work. Raising awareness and transparency amongst employees and employers (e.g., around wage and performance evaluation processes) is an important first step.

- Promote fair distribution of housework and childcare responsibilities at home, by shifting outdated gender norms through behavior change campaigns and through family-friendly policies such as equal and adequate maternity and paternity leave policies that encourage an equal sharing of child-caring responsibilities. Making childcare affordable and accessible will also enable parents, especially mothers, to stay in the labor market when they choose to do so.

See the full report which we co-authored with Tshegofatso Desdemona Thulare and Ramaele Moshoeshoe.

Related:

Join the Conversation