But young people don’t just need jobs, they also create them. Therefore, what matters most is to make sure that the education system delivers the skills needed in emerging economies, and incubates entrepreneurs. In turn, as people become more educated and healthier, they will have fewer children. This is already happening: As Kenya continues to welcome about a million new citizens each year, family size is slowly declining.

This creates the possibility of a “demographic dividend”, similar to what underpinned economic take-off in other parts of the world. Today, Kenya has more adults than children, more potential workers than dependants, and an increasingly urban population. Almost mechanically, this frees up resources: if families have higher incomes but fewer children, each child receives more attention (personal and financial). Nationwide, the demographic dividend can translate into an education dividend as well. And education matters: as it is one of the single most powerful predictors of future income and social mobility.

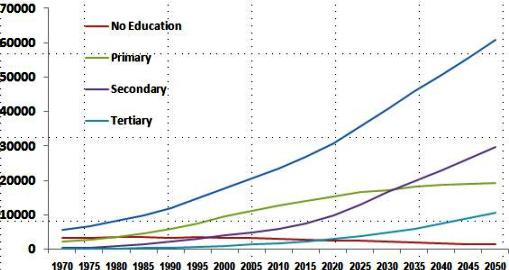

Using new statistical methods, the Vienna-based Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital has produced some fascinating analysis, which projects education attainment into the future. According to these projections, Kenya’s education landscape is changing rapidly. At the time of Independence, most adult Kenyans had received no formal education. Since then, there have been two statistical watershed moments, and more to come. First, since 1980 the number of Kenyans with primary education has exceeded those with no education; just over a decade later, those with secondary education also exceeded those with none.

Today, a majority of Kenyans have had the benefit of attaining basic education, and almost all children are going to school, except in northern and north-eastern Kenya.

This country has 25 million people above the age of 15. About half of them (13 million) have received primary education (up from 11 million in 2000). But the most rapid increase has been in secondary education. In 2000, Kenya had less than four million people with secondary education. This number has risen to seven million today, and is expected to triple to 20 million by 2035. Tertiary education is also picking up from a low base and by 2020, the number of Kenyans with a university degree is also expected to exceed those without any formal education. Before 2050, there will be a final major cross-over: by 2035, more Kenyans will have received secondary education than primary; Kenya will have 45 million people above the age of 15 (and some 70 million in total) 45 per cent will have completed secondary education, 44 per cent primary education, and six per cent university; and only five per cent of Kenyans will not have had any formal education. Just a few years ago (in 2000) three quarters of Kenyans had no or just primary education (see figure).

Figure: Kenya’s Education Dividend

Source: Adapted from Jesus Crespo Cuaresma, Vienna University.

But putting children in school is only a first step: they also need to be learning something (useful) there. The focus must now switch from quantity to quality of education.

To get good learning outcomes will require significant investments in educational personnel and hardware. Kenya has some 250,000 teachers, which is not enough: while class sizes are somewhat manageable in the cities, they remain very large in rural areas. Moreover, on average, 13 percent of teachers do not report to school. And many struggle to teach core foundational reading and mathematics skills. As a result, too many children fail basic reading and mathematics tests, even with several years of schooling. Teachers and administrators themselves need to be trained: for instance headteacher leadership is critical to ensure high standards, and to interface with parents.

Unless these quality bottlenecks are tackled, there is no guarantee that Kenya’s education dividend will pay off. Kenya has taken the necessary first step: most children are now in school and are staying there longer than most of their parents did. Now let’s make the most out of this revolution by ensuring that schools are a place where children actually learn.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Helen Craig and the World Bank education team in Nairobi provided valuable input.

Follow Wolfgang Fengler on Twitter@wolfgangfengler.

Join the Conversation