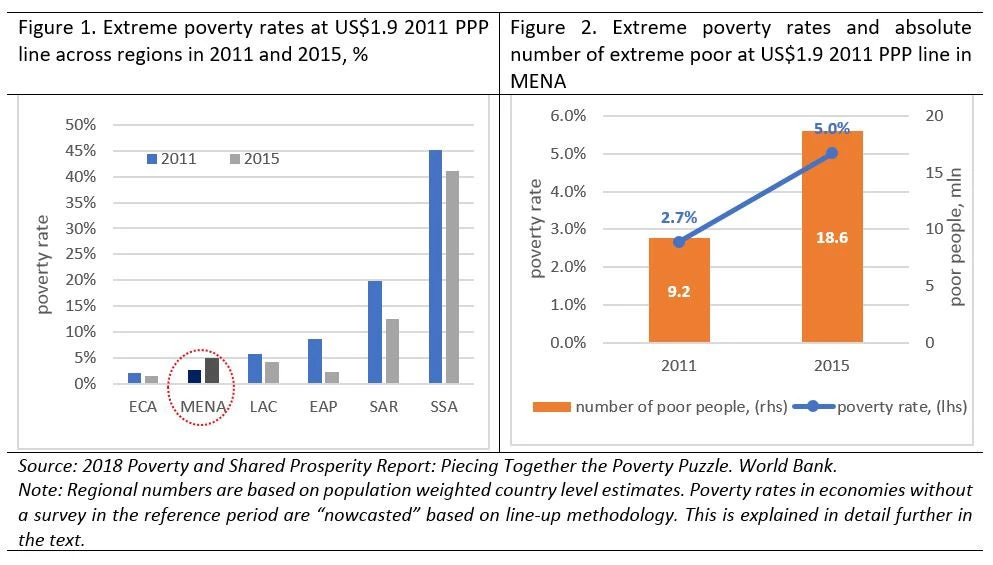

When the World Bank recently released the 2018 Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report; Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle , which includes the global and regional poverty estimates, the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) stood out for two particular reasons. First, the MENA region is the only region where the extreme poverty rate increased between 2011 and 2015 (figure 1). Extreme poverty increased from 2.7% in 2011 to 5% in 2015, doubling the number of extreme poor to 18.6 million living on less than $1.90 a day (figure 2). Second, this was the first time that regional estimates were reported for MENA after several years of poor data availability and issues with 2011 Purchasing Power Parity conversion factors in selected countries.

It wasn’t surprising to note that the increase in extreme poverty was driven by conflict-affected Syria and Yemen. Extreme poverty in Syria increased from almost zero to more than 20%, while in Yemen, extreme poverty more than doubled to reach 41% in 2015. These trends are consistent with what country-level studies estimate. In other developing MENA countries, extreme poverty remained very low and even declined.

Challenges to estimating the MNA regional poverty numbers

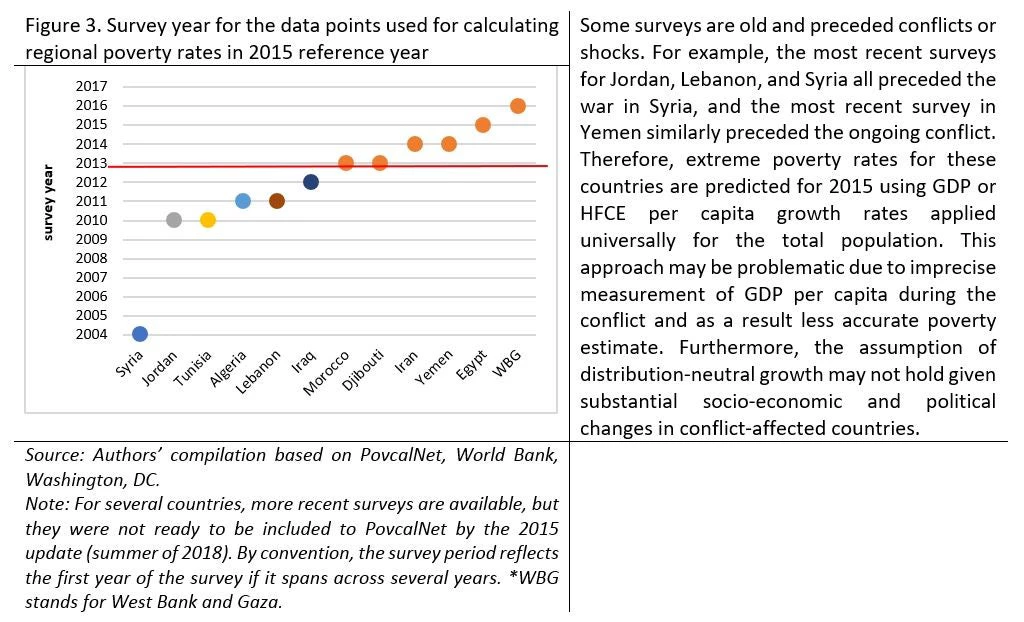

Given the dearth of data in the region, estimating up-to-date global and regional poverty numbers is not a trivial task and to calculate the 2015 regional numbers we used several important rules and assumptions that made estimation simple and transparent.

To compare the number of poor people across countries and compute regional aggregates, country estimates must be “lined up” or nowcasted to a common reference year – currently 2015. Usually survey years are earlier than the reference years and survey consumption or income is adjusted by real growth rates in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) or household final consumption expenditure (HFCE) per capita. For simplicity, we assume that inequality remains unchanged. Therefore, accuracy of lined-up numbers will depend on how old the underlying data is, on the accuracy of GDP and HFCE per capita estimates, and on how economic growth relates to household consumption.

Availability of and access to the most recent household survey data are particularly important issues in MENA. As can be seen from figure 3, half of the available surveys in MENA were conducted before 2013.

Having outdated surveys may even result in the inability to report regional numbers. In order to report regional poverty rates, surveys should cover more than 40% of the total regional population. Additionally, surveys should have been conducted within two years of the reference period (either before or after). In our context, this would imply that any survey conducted before 2013 will not be counted in the population coverage for 2015. The current population coverage for 2015 estimates in MENA is about 64% and may drop if newer surveys are not included for the next update.

Another issue with measuring poverty in MENA is that household surveys are not typically designed to count non-residents, and they will most likely miscount displaced residents, who are often amongst the most vulnerable groups. On top of this, monetary poverty many not be very informative in the presence of violent and disruptive shocks, and non-monetary dimensions might provide a more complete and meaningful picture of well-being.

Having accurate regional poverty estimates is crucial for global poverty monitoring. Further work on improving availability and access to household data, as well as collection of household data that incorporate difficult-to-reach populations will help to refine estimates of monetary poverty in MENA. However, given the difficulties in collecting traditional household data and the multiple deprivations that are prevalent during conflict, using non-traditional surveys and analyzing a broader range of deprivations should complement analysis of monetary poverty trends in the region.

Join the Conversation