Carbon pricing is increasingly being used by governments and companies around the world as a key strategy to drive climate action while maintaining competitiveness, creating jobs and encouraging innovation. The importance of carbon pricing was amplified in the run up to the global climate change agreement in Paris last December.

As countries move towards the implementation of the Agreement, it is the focus of a World Bank conference in Zurich this week which brings together over 30 developed and developing countries to discuss opportunities and challenges related to the role of carbon pricing in meeting their mitigation ambitions.

The World Bank Group, through several initiatives, provides financial and technical assistance to a number of countries leading the way to put a price on their emissions. Part of this support is practical advice on how to design and implement specific emission reduction instruments such as an emissions trading system or a carbon tax.

This week, the World Bank’s Partnership for Market Readiness (PMR) – jointly with the International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP) – launched “Emissions Trading in Practice: Handbook on Design and Implementation”, a new guide for policymakers that distills best practices and key lessons from more than a decade of practical experience with emissions trading worldwide. The preparation of this Handbook involved experts from the Environmental Defense Fund (US), Motu (New Zealand), Vivid Economics (UK), Öko-Institut (Germany), MIT (US), and Tsinghua University (China), as well as input from over 100 international policy practitioners and technical experts.

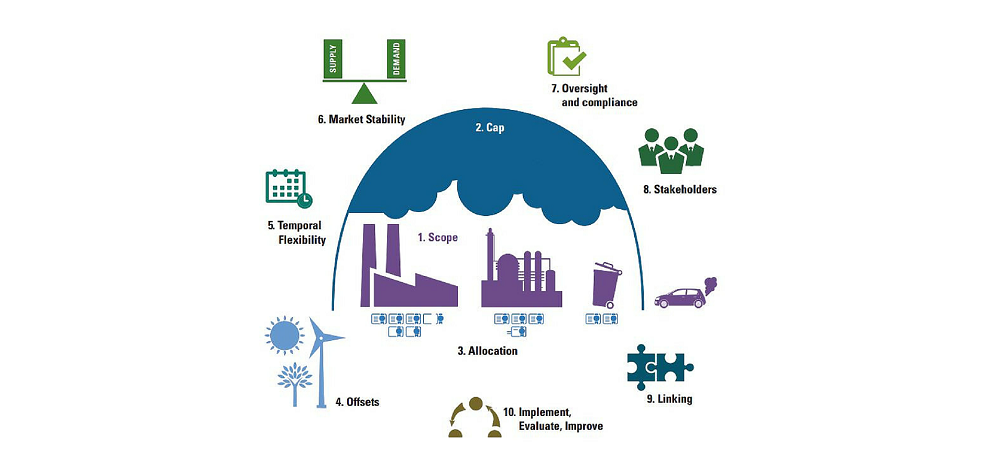

Under an ETS, the government imposes a limit (cap) on the total emissions in one or more sectors of the economy, and it issues a number of tradable allowances not exceeding the level of the cap. Emissions trading provides reasonable confidence about the future level of emissions, which makes it an attractive policy option for many governments. To help policymakers design, implement and operate an ETS, the Handbook sets out a 10-step process of decisions and actions to be taken.

Setting the scope of the ETS (i.e. geographic area, sectors, emissions sources, and GHGs to be regulated) is step one in the process. Policymakers must then collect robust emissions data, and determine the level of the cap and its long-term trajectory – reflecting the jurisdictions’ overall climate change ambition mitigation.

Once this is done, emissions allowances are distributed to regulated entities in a way that reflects the overall cap while addressing potential leakage issues (like the concern that carbon pricing causes sources of emissions to move rather than genuine emission reductions), distributional impacts, as well as opportunities for governments to raise revenue.

To allow covered entities to meet compliance obligations under the cap at a lower cost, the government can then consider allowing the use of offset credits, generated from uncovered sources and sectors in the ETS. It then needs to set timeframes for the reporting and compliance period, balancing flexibility of timing against the certainty of achieving reductions by allowing participants to “bank” (carry over) or borrow allowances across compliance periods.

A next step is to address potential volatility and uncertainty about prices through market stability design features, such as a price floor, ceiling, or allowances reserves. A rigorous approach to enforcement of participants’ obligations and to government oversight of the system must also be defined. This includes technical, legal, and administrative considerations around the monitoring, reporting, and independent verification of emissions, penalties for noncompliance, and oversight of the market to address risks of fraud and manipulation.

Also, continuous engagement with stakeholders to understand and address respective positions and concerns is critical to avoid policy misalignment and ensure public and political support as well as encourage collaboration across government and market players.

Allowing regulated entities to use the units issued under an ETS in another jurisdiction, or “linking”, broadens flexibility as to where emission reductions can take place, can also improve market liquidity, help address leakage and competitiveness concerns, and facilitate international cooperation.

Finally, allowing for regular reviews of ETS performance supported by rigorous, independent evaluation will enable continuous improvement and adaptation to changing circumstances.

Currently, ETSs are operating across four continents in 35 countries, 13 states or provinces, and seven cities, covering 40 percent of global GDP with additional systems under development. For example, in China, we are eagerly awaiting a national carbon market to become operational in 2017 as a key driver of the transition to a low-carbon economy. Building on the experience of seven ETS pilots that are already in force, the PMR is supporting China in developing their national ETS. This support includes analytical work and consultations on various components of the ETS design, such as the role of state-owned enterprises and the power sector, as well as private sector readiness activities.

While political commitment is critical to implement an ETS, in order for it to be successful, policy decisions cannot take place in isolation. Collaboration with stakeholders, including the private sector, is key to understanding the impacts of an ETS on competitiveness and exploring the ways to address them. Private sector involvement is also critical for building consensus and reducing the risk of future discord. To this end, the PMR established a long-term and systematic collaboration with the Business Partnership for Market Readiness (B-PMR) initiative of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA). As part of this joint effort, the recently organized event, China’s National Carbon Market: An Industry-to-Industry Dialogue, aimed to do exactly that - enhance private sector engagement and readiness on emissions trading by bringing together the Chinese authorities and a number of international and Chinese companies to discuss best industry practices and test ETS simulations.

China’s effort to develop its national carbon market is an extraordinary example of climate leadership. That said, it’s certainly not the only one. As more countries pursue carbon pricing as a way to reduce their GHG emissions, the PMR technical assistance will be even more critical. We hope that the ETS Handbook will help countries address challenges along the way, one step at the time.

Join the Conversation