Petugas kebersihan di Pelabuhan Tanjung Priuk, Jakarta. Foto: Josh Estey/World Bank

Petugas kebersihan di Pelabuhan Tanjung Priuk, Jakarta. Foto: Josh Estey/World Bank

Suryo drives a bajaj (a three-wheeled cab) in the sprawling metropolis of Jakarta. He used to work as a production worker in a textile factory, but he lost his job during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Buoyed by rapid urbanization, and after a few unsuccessful attempts to find work as a tradesman, Suryo decided to become a bajaj driver. He now spends all day plying the dusty, congested thoroughfares, waiting for customers to hop on. On a good day, Suryo earns around Rp. 100,000 or US$6 – just enough to feed his family of four for a day.

Like most other Indonesians, Suryo does not have a “middle-class” job. This is defined as a job that pays middle-class wages (at least Rp. 3.8 million per month, in 2018 prices) and provides a level of income security and benefits that are consistent with middle class expectations.

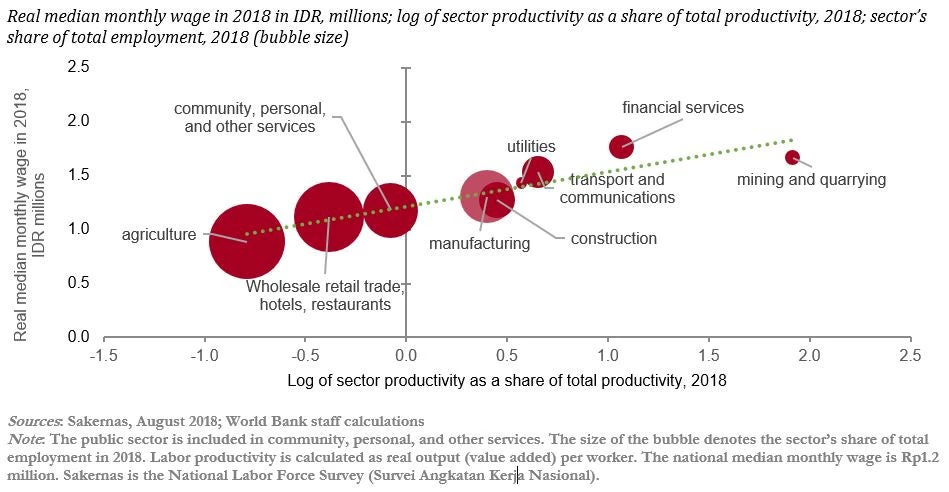

Among the 85 million income earners in Indonesia in 2018, only 13 million can be considered as holding middle class jobs. Fewer still (3.5 million) earn more than a middle-class wage, enjoy full social benefits , and hold an indefinite-term employment contract. These jobs are mostly concentrated in more productive sectors, which employ few workers (Figure 1).

Figure 1: More productive sectors tend to pay better wages, but employ few workers

At first glance, the insufficient number of good, middle-class jobs in Indonesia is puzzling. Like many other East Asian economies, Indonesia experienced rapid industrialization through growth in manufacturing exports and urbanization in the 1980s and 1990s, leading millions of workers to shift from agricultural to non-agricultural jobs, especially manufacturing jobs. This ‘first wave’ of structural transformation boosted labor income and hence facilitated a large reduction in poverty.

However, the nature of structural transformation changed after the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis. Indonesia’s economy shifted into a natural resource-based growth model, hurting the quality of jobs created. During this commodity boom, real exchange rates appreciated against the US and other Asian peers, and combined with a weak business environment hurting competitiveness and foreign direct investment, the share of manufacturing value added, exports, and employment fell, resulting in premature deindustrialization. Although workers continued to move out of agriculture during this second wave of structural transformation, they mostly transitioned into jobs in low value-added services sectors, for example, as owners of mom-and-pop stores or food stalls, and motorcycle or bajaj ride-hailing taxi drivers, rather than into manufacturing, for example, as production workers. Such low-end, low-paying jobs were more productive than agricultural activities, but only very slightly. As the commodity boom came to a halt post 2012, Indonesia did not recover to a growth model driven by manufacturing exports.

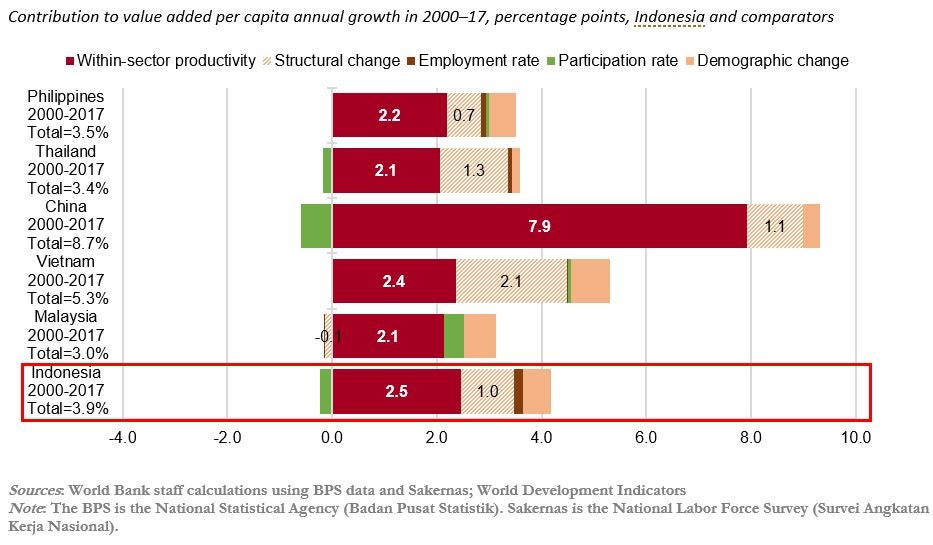

The lack of middle-class jobs today is therefore a result of the limited productivity gains from structural transformation. While labor productivity growth has been the main driver of Indonesia’s economic growth over the last two decades, most of the improvements in labor productivity have occurred due to efficiency gains within sectors (Figure 2), rather than the movement of workers between sectors (specifically, from lower to higher-productivity sectors).

The total contribution of structural change to value-added per capita annual growth in Indonesia over 2000-2017 was merely 1 percentage point, much smaller than in Vietnam (2.1 percentage points), Thailand (1.3 percentage points), and China (1.1 percentage points).

Figure 2: Labor productivity growth has driven economic growth in Indonesia, but the contribution of structural change is smaller than in other countries

The immediate priority in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis is to protect existing jobs. However, getting the next wave of structural transformation ‘right’ will be critical to create more middle-class jobs in the medium term . To accelerate the transition of workers and economic activities from low to higher-productivity jobs, firms, and sectors, the government could implement policies to prioritize investments in sectors that are most amenable to the creation of middle-class jobs – such as ICT, finance, health, education, and manufacturing – and hence boost labor demand in these sectors.

The government could also facilitate the movement of workers into higher-productivity jobs, firms, and sectors by closing information gaps through complete and dynamic labor market information systems and job-matching mechanism; legislation that does not disincentivize job changes; and unemployment insurance to finance job search and relocation.

Finally, continuing to invest in the skills of current and future Indonesian workers is critical to ensure that the local workforce can fill new vacancies for middle-class jobs . Providing support to at-risk students to encourage them to complete secondary school; teaching nonroutine interpersonal, analytical, and digital skills to students and adults learners though revised curricula and pedagogical methods; enhancing the quality of technical and vocational education and training; and finally, providing tailored support to groups with special labor market needs, such as women, youth, and workers with disability, will help more Indonesians to take advantage of better-quality jobs.

To find out more about the jobs reform agenda in Indonesia, access the recently published report here.

Related link:

Join the Conversation