What to do?

How do you strike a balance between the immediate needs of students *right now* and an education system's requirements to train teachers to help meet such needs over the long term?

The traditional approach to dealing with such a challenge in many places has been to focus primarily on pre-service training, gradually introducing new teachers into classrooms over many years who have prepared to teach the subject through dedicated courses of study at teacher training colleges, together with occasional in-service professional development activities for existing teachers (normally during holiday breaks). In Uruguay, it was recognized that the gap between the abilities and capacities of many teachers to teach English, and student needs to learn English (which became compulsory in 2008) was so huge in many parts of the country that they needed to do things differently than they had done in the past. Instead of having teachers learn English separately, might it be possible to have them learn alongside their students, in their own classrooms?

As it happens, almost a decade ago Uruguay began its ambitious and innovative Plan Ceibal, which (among other things, and as profiled in a number of previous posts on the EduTech blog) made this small South American nation the first country to connect all of its schools to the Internet and provide all primary school children with a free laptop.

Given the technical infrastructure and know-how that was developed under Plan Ceibal, Uruguayan policymakers asked themselves:

Now that all of the schools are connected to the Internet,

and all students have their own laptops,

might it be possible to offer high quality

English language instruction live over the Internet,

connecting to teachers many miles away from the schools?

and all students have their own laptops,

might it be possible to offer high quality

English language instruction live over the Internet,

connecting to teachers many miles away from the schools?

The answer to this question, it would appear, is 'yes'. Working out of its remote teaching center in Buenos Aires, its global digital learning hub in the neighboring country of Argentina, the British Council is beaming out English lessons to children in hundreds of individual classrooms across Uruguay, complementing and supporting the work of local teachers in these same classrooms. This is not a 1-to-many broadcast of the sort commonly done in many countries through the use of broadcast television, but rather connects individual classrooms in Uruguay with individual teachers sitting in other places. Some of these English teachers are based in the Uruguayan capital of Montevideo, many others next door in Argentina, and still others much further afield -- including halfway around the world in the Philippines and the UK! Along the way, the capacity of local teachers, who continue to lead English classes on their own other days of the week, is developed, through their interactions with and observations of the remote teachers.

---

A few months ago, some folks at British Council offices around the world shared lessons from what they've been doing, and learning, along the way with World Bank staff interested in learning more about practical issues related to 'distance teaching'. This was done using the same online tools that the British Council uses to support its remote teaching activities in Uruguay, and elsewhere. (As it happens, the choice in advance to use 'distance learning' tools here was fortuitous, as this was one of the winter days when offices were closed in Washington, DC due to inclement weather.)

how it works

English instruction for around 25 students occurs three 45-minute classes a week -- once with the remote teacher (in which the classroom teacher also participates), plus two classes led by the classroom teacher herself (typically building on and practicing what was introduced and practiced during the 'remote' lesson. Quite often, the local classroom teacher speaks very little English, and so she is, in some sense, learning along with her students, both by improving her English language abilities, and through exposure to pedagogical strategies in how to teach English. (Sometimes, the remote teacher utilizes elements of so-called 'scripted' lessons that the classroom teacher then utilizes in subsequent activities.) Over the course of a week, over 3000 classes are conducted this way in over a 1000 Uruguayan schools.

This model is conceptually similar in many ways to what typically occurs in a number of countries through 'interactive radio instruction'. That said, 'remote teaching' of this sort represents a gigantic leap forward over IRI: the remote teacher appears on a large screen in the classroom (giving her a 'physical presence' of a sort) and a remotely operated camera provides the remote teacher with the means to zoom in one individual children's faces, or zoom out to see what the class as a whole is doing. An LMS (learning management system) further enables the sharing of messages and additional content between the remote teacher, the classroom teacher and their students.

If you want to see what this looks like in practice, have a look at these videos. Here is more information from the British Council web site, some comments from remote teachers themselves, and a related hour-long presentation delivered using some of the same tools utilized in the remote teaching project.

When it comes to the use of technology use in education, there has long been talk of the potential for so-called '

blended learning' (a term I actively dislike; isn't all learning a blending of various sorts, with technology increasingly involved in vaarious ways?). What is happening in Uruguay here is in many ways a form of '

blended teaching'.

challenges

Teaching remotely brings with it many very obvious challenges. How can you monitor the quality of teaching and learning, observe classroom behaviors and maintain discipline and student engagement in a remote teaching environment? By conducting these classes at such a massive scale, the British Council and Plan Ceibal have been developing an increasingly good, hyper-practical understanding of pedagogical practices that work (and don't work) in a remote teaching environment. The Uruguayan experience is demonstrating that not only is it possible to present information (distance learning activities utilizing television and radio have shown this to be the case for many decades), but also that it's possible for teachers and students to interact with each other in ways that support and enable learning. It's this interaction -- between teachers and students, between teachers, and between students -- that the folks at the British Council say is what students and teachers say they want, and what the remote teaching methodologies strive to help bring about.

Teachers and students who have spent time in classrooms where ICT use has been integrated into various teaching and learning practices know from firsthand experience that, at some point, whatever can go wrong, will go wrong. How do they deal with the inevitable technology problems that pop up during some distance teaching activities in Uruguay? Here are a few very practical ways:

- Plan Ceibal, the national educational technology initiative in the country, has technical people on call (e.g. to help with connectivity problems).

- Teachers are encouraged to plan and test the equipment before test beforehand (always a good plan of action, of course -- but not always possible).

- Students receive a printed 'user guide' that helps orient them and complements what is happening during a remote teaching session.

- Remote and classroom teachers open up an electronic 'backchannel' (via Skype, testing, WhatsApp, etc.) so that they can communicate with each other about logistical issues.

- Teachers receive training on what to do when the technology doesn't work -- and to anticipate that such things will happen, no matter how well prepared they are, and so not be frightened of these difficulties when they do occur.

- Sometimes the remote and classroom teachers (both of whom have mobile phones) call each other and talk through approaches to dealing with technology difficulties.

Do these approaches always 'solve' the related technical problems? No, of course they don’t, not always, but over time, as experience accrues and teachers and students get more comfortable with the remote teaching approach, technical challenges are decreasing, and the ability to work around them becomes yet another skill that participating teachers had added to their pedagogical repertoire.

research

A number of related research activities are underway to try to document [pdf] what is happening under this project, and the impact it is having. According to the British Council, preliminary research seems to suggest (unfortunately I have no related link to share with you here) that there are virtually identical outcomes in Uruguayan classrooms which utilize remote English teachers and those which feature Uruguayan English teachers who have been trained 'face-to-face'.

side note: Given the huge investments made across its entire primary and secondary school systems in educational technologies, Uruguay represents a fascinating and potentially quite fertile laboratory for education researchers interested in investigating how ICTs can be used to support and enable lots of different teaching and learning activities and processes, as well as what impact this use is having. Recognizing this, the Uruguayans have set up a dedicated

center to help support such research activities, as well as made available related

funding.

Remote teaching of English seems to be working in Uruguay. But what might this effort reveal or suggest about other contexts, in other places? The British Council is utilizing similar approaches in tools in a number of other places around the world to help teach English (in remote parts of the Amazon, in Pakistan, in refugee camps), and is encouraged by hat it is seeing, and learning, from these efforts. But it certainly isn't hard to imagine that such approaches might be relevant in circumstances where improving English language instruction is not the goal. After all, there are scores of countries around the world that are currently buying lots of devices and rolling out connectivity to schools in places where existing teacher training and professional development simply isn't working well at all -- or where what is working simply doesn't scale. And: It is perhaps worth noting that, in places like Uruguay where the infrastructure is put into place to enable the remote teaching of English (and not only the physical infrastructure, but the related pedagogical know-how on how to utilize it effectively), this infrastructure can then be used to support teaching and learning in other subjects as well. (As it happens, the British Council is currently exploring how to utilize and adapt some of its 'distance teaching methodologies' honed in its experience in Uruguay to promote mentorship for entrepreneurs in various places around the world.)

trade-offs

When it comes to trade-offs that education policymakers around the world have traditionally faced when debating whether or not to roll out approaches to 'distance education', they have often asked themselves: Do we compromise on price, or on quality? 'Distance education' may not yield the type of results we would hope for, but it is a lot cheaper, and so we can reach more students with it. Fair enough: There are limited funds available to finance public education in most countries, and such trade-offs are thus par for the course. But really, given the stakes involved, when it comes to education, it is perhaps worth asking: To what extent can we *really* afford to compromise on quality?

wider relevance?

Huge sums are being devoted to rolling out and improving connectivity for schools in many education systems around the world -- in many cases, without clear ideas at a practical level on what exactly this connectivity will be used for. While Uruguay is a country hardly known known for its prowess on the ice at the Winter Olympics, I am reminded here of the words of Walter Gretzky, who urged his son (who later went on to become the greatest hockey player in the world, if not ever) to ' skate not where the puck is, but where it will be'. Uruguay, given its large investments in connectivity and devices for students, is demonstrating some very practical ways that it might be possible to make productive use of such investments going forward, doing some things that previously simply weren't able to be done. While it may take quite some time, and no doubt there will be many (expensive) misfires along the way, I expect many middle and low income countries will eventually have a technology infrastructure available in their schools like what Uruguay has today. What will they do with this infrastructure once it’s in place?

By demonstrating one possibility of where 'the puck might be', connecting teachers in Manchester, Manila and Montevideo with their counterparts in primary schools across in Uruguay to help teach English to students, the remote teaching initiative from Plan Ceibal and the British Council presents educational policymakers in some other countries with a provocative picture of some of what might be possible to do in the future.

You may also be interested in the following posts from the EduTech blog:

- Interactive Educational Television in the Amazon

- Next steps for Uruguay's Plan Ceibal

- What's next for Plan Ceibal in Uruguay?

- What happens when *all* children and teachers have their own laptops

- How do you evaluate a plan like Ceibal?

- Interactive radio instruction: A Successful Permanent Pilot Project?

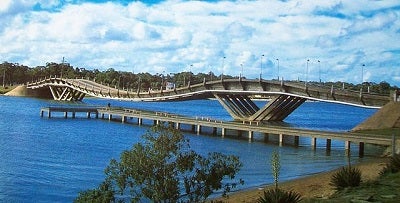

Note: The image used at the top of this post of Puente Barra Maldonado in Punta del Este, Uruguay ("viewed from afar, some things seem sort of strange") comes from Wikimedia Commons and is in the public domain.

Join the Conversation