Three quarters of a century since the opening of the first McDonald’s, the fast food chain operates around 34,000 outfits in around

120 countries and territories across all continents. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), however, – a region of 48 countries and almost a billion people - only South Africa and Mauritius have been able to attract this global food chain.

Three quarters of a century since the opening of the first McDonald’s, the fast food chain operates around 34,000 outfits in around

120 countries and territories across all continents. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), however, – a region of 48 countries and almost a billion people - only South Africa and Mauritius have been able to attract this global food chain.

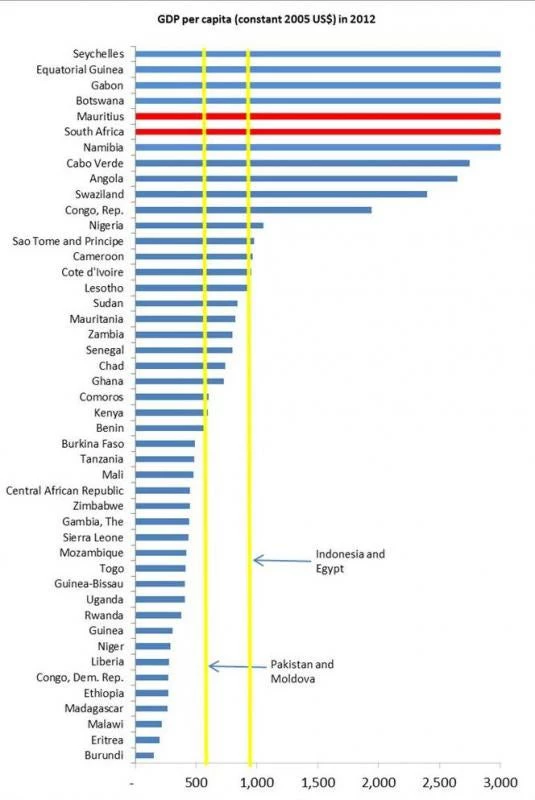

This peculiarity cannot be explained only by the fact that the region is poor. The company has found a market in about 30 countries with GDP per capita of less than US$ 3,000 (in constant 2005 US$) at the time of their first McDonald’s opening. Hamburgers, Cheeseburgers, and Big Macs are also on offer in a dozen of low-income countries as well. When the first McDonald’s opened in Shenzhen in 1990, China’s GDP per capita was less than US$ 500 per person. Of course, Shenzhen’s per capita income was several times higher, but the company has also found a market in Moldova since 1998 when the GDP per capita of the 3 million person country was less than US$ 600 per capita. There are many cities in SSA today that have higher income, population concentration, and tourists than what Chisinau had in 1998; yet they do not have a McDonald’s. As a matter of fact, 22 SSA countries today have higher income per capita than what Moldova or Pakistan had when the first McDonald’s opened there, and 15 of them have higher income per capita even than what Indonesia or Egypt had at their McDonald’s openings (see chart).

Chart: Sub-Saharan Africa is rich enough for McDonald’s

What then explains SSA’s inability to create a favorable environment for global food chains? It is hard to imagine that an entire continent is disinterested in Big Macs and fries. Actually, South Africans seem to love it as the chain has opened more than 150 outlets since it established itself in 1995. The investment decision to open a McDonald’s, as for any other business, rests on the feasibility and profitability of the product offering. Three factors, beyond the market’s buying power (income), are likely to be found decisive. First, it is an issue of access to finance: local investors would need hundreds of thousands of dollars to bring the McDonald’s (or other global fast food chain) brand – not an easy sell in the region with the least developed banking sector (measures through the share of credit to private sector to GDP). Then, there is the question of security of investment which depends on crime levels, state intrusion (including governments’ openness to foreign investors) and corruption. Finally, ingredients have to be imported in an efficient manner through participation in global supply chains, thus infrastructure, logistics and trade regulations come into play. When McDonald’s opened in Moscow in 1990, it had to import 90 percent of the around 300 ingredients that go into the menu. The SSA countries seem to be missing one or more ingredients to have the red neon sign with a golden yellow “M”.

Having the above ingredients may mean more to a developing country beyond the taste that comes with the burgers. In almost 60 percent of cases, developing countries grew faster in the five years, compared to the previous five, following the opening of the first McDonald’s. Moreover, the acceleration of growth is substantial (from 1.7 percent to 6.3 percent annual growth for those countries that had GDP per capita of less than US$ 1,000 at time of opening). What this means is that McDonald’s may be viewed as one of the tipping points for when a country has amassed sufficient urban middle-class, investment security and supply chains for economic take off. In the case of SSA, the ingredients are not there yet, but the recent economic trends and reform advancements may bring more red and yellow neon lights across the continent’s capitals.

As first published by the World Bank’s Future Development blog

Join the Conversation