The design of the safety net program is perfect; it is based on the latest data and evidence; it enjoys political support at the highest levels, and it has sufficient financing.

So why can this safety net program not even get started after a year?

Maybe the answer has something to do with institutions. Accounting for the formal and informal “rules of the game” for social safety nets is key to the success of any program or system. In our chapter “Anchoring in Strong Institutions to Expand and Sustain Social Safety Nets” in the recently-released regional study on safety nets, we discuss some critical aspects of institutions that can make (or break) a social safety net program and how these evolve as programs grow in Africa.

What are institutions?

Institutions hold the rules that shape all aspects of social safety nets, ranging from the eligibility criteria to the regulations and procedures that govern the operations of the organizations that deliver the social safety net programs (including mandates and human resource policies) to sectoral laws and regulations. As outlined in the World Development Report 2017, institutions also extent beyond formal rules to informal institutions, such as routines, conventions, customary practices.

Building a social safety net system does not necessarily require a focus on a single entity or agency to manage programs. Instead, it calls for a focus on the institutions, including the processes, that guide the design and delivery of social safety nets within government systems.

For social safety nets in Africa are to be adequately scaled up, institutions must evolve along multiple parameters including the level of anchoring in laws and policies; mechanisms for coordination and oversight; and arrangements for management and delivery. Small pilot interventions may show results and contribute to building political support for the expansion of social safety nets, but broadening coverage typically requires some consolidation.

A legal framework to anchor social safety net systems

Across the region, policy commitments to social safety nets are embedded in international conventions and declarations. The presence of these laws or legal frameworks may signal an important step toward the firm anchoring of safety nets in Africa. But to be sure, these laws need to be matched with political support and financial resources to deliver.

All countries in Africa now include social safety nets in their national development strategies. Similarly, social protection policies and strategies have become common across Africa. But, they are often general and not fully implemented. If it is aligned with political interests and backed by sufficient resources, a legal framework can act as a strong anchor for a social safety net. South Africa offers an example of how political incentives may be aligned with a legal framework for social safety nets.

Safety nets need to be rooted in institutions that set policies and handle coordination and oversight

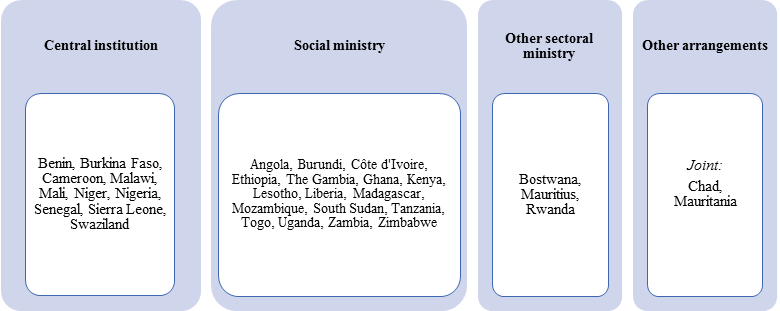

Until recently, there were few ministries responsible for social protection policy or coordination in African countries and thus choosing where to vest this authority was often the first step in setting the formal institutions for safety nets. This choice typically results from considering ministerial mandates and political power, with initial decisions shaping the evolution of social safety nets in a country. In the region, responsibility for policy oversight and coordination is most often vested in a social ministry (Figure 1). This choice may reflect a desire to name a ministry that is already mandated to promote policies that support the poor and vulnerable. Social ministries may have the strongest mandate to support the poor, their financial resources and political influence are often limited.

Central ministries or offices—the office of the prime minister, the office of the president, or ministries of finance and planning— lead policy and coordination in some countries. While central ministries may enjoy considerable authority, the organizational culture may be less sympathetic to the need of the vulnerable for social transfers.

In countries where humanitarian programs are prominent or in fragile settings, NGOs and development partners often play critical roles. The coordination and oversight of these programs are often of practical importance because of their size and the political nature of the response to shocks.

Figure 1: Social Ministries Are Not the Only Policy, Oversight, and Coordination Entities

Implementing safety nets require the right technical skills but also a home aligned with the aims of the program

Social safety net programs are usually housed in a ministry with a mandate that aligns with the aims of the program: programs with a social protection focus (such as a safety net to categorical groups considered vulnerable) tend to be housed in social ministries, while programs that focus on more productive aspects are in ministries specialized in rural development or agriculture, or infrastructure.

Management arrangements influence program effectiveness and sustainability. Lodging programs within government departments ensures the use of country systems. But, this means abiding by ministerial procedures and hiring standards. Programs delivered by semiautonomous government agencies (SAGAs) are often able to apply their own rules and standards. In contrast, a project implementation unit in a Ministry can address key gap in government capacity.

Programs sometimes shift institutional homes. A program that emerges in response to an emergency may be put in a high-profile agency, such as an office of the president. As the program matures, a social ministry or agency with a policy mandate to serve the vulnerable may become a more appropriate home. This evolution is seen in countries in Latin America but not yet in Africa, where social safety net programs are relatively.

Creating incentives to encourage individual actors to deliver results

Programs may be delivered by staff who are fully dedicated to the program or by staff responsible for a range of programs, including the social safety net. Staff may be civil servants or temporary staff on fixed-term contracts. Some key functions, such as administering payments, organizing training activities, or even running the program implementation unit, can be contracted to private sector providers. These differing arrangements create various incentives for the staff and thus influence the quality of safety net support provided to beneficiaries.

This blog post is based on “Anchoring in Strong Institutions to Expand and Sustain Social Safety Nets,” Chapter 4 of the 2018 regional study Realizing the Full Potential of Social Safety Nets in Africa.”

Blogs based on previous chapters include:

Chapter 1: Social safety nets in Africa: Everywhere and growing, but going where?

Chapter 2: Safety nets boost consumption levels of the poorest across Africa

Chapter 3: The politics of safety nets: Don’t shy away

Join the Conversation