Sub-Saharan Africa produces more than 50 percent of the world’s cassava (aka manioc, Tapioca, and Yucca), but mainly as a subsistence crop. Consumed by about 500 million Africans every day, it is the second most important source of carbohydrate in Sub-Saharan Africa, after maize. The leaves can also be consumed as a green vegetable, which provides protein and vitamins A and B. As an economy advances, cassava is also used for animal feed and industrial applications.

Described as the “Rambo of food crops” cassava would become even more productive in hotter temperatures and could be the best bet for African farmers threatened by climate change.

Cassava is drought resistant, can be grown on marginal land where other cereals do not do well, and requires little inputs. For these reasons it is grown widely by African small and poor farmers as a subsistence crop. However, cassava’s potential as an income-earning crop has not been widely tapped.

Cassava presents enormous opportunities for trade between areas with food surplus and food deficit. Currently, a large shortfall of the regional food supply is filled by cereals bought in the international market. For cassava to become an income-earning crop at intra-regional market for small farmers in Africa, two main obstacles remain: post-harvest processing and regional trade barriers.

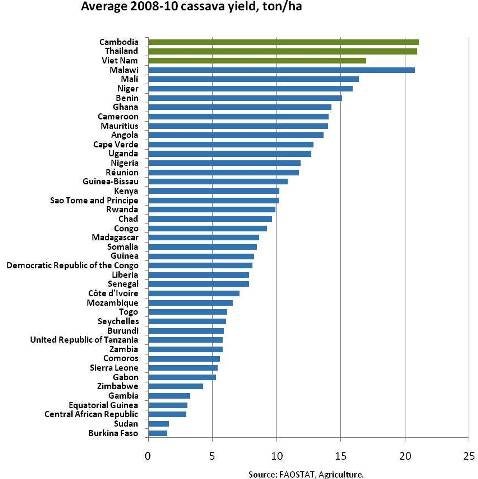

Because transporting raw cassava over long distances is uneconomical and logistically difficult due to its high water content, fresh cassava must be processed into products suitable for transportation in order to be sold in markets. Cassava chips are transportable as a semi-processed product for animal feed, which involves simple procedures and can be accomplished at farm gate by small farmers with the current technology. However, processing cassava for human consumption requires more complicated procedures, as well as water, which could be scarce in certain rural areas. Low yield can also hamper small farmers’ profitability, but a few African countries have already achieved yields comparable to that of Thailand’s, the world leading cassava exporter.

After cassava is processed into a transportable form, cross-border trading can be challenging, depriving farmers of profits. For example, it takes 32 days to export and 38 days to import in SSA, while it takes only 23 days to export and 24 days to import in Asia. It is estimated that the cost due to the NTBs in Southern Africa alone is equivalent to more than $1 billion per year.

Commercialization of cassava is already happening at the community level. However, cassava is yet traded at intra-regional level. Currently, the limited post-harvest processing capacity at industrial level and the high-cost added by NTBs (in some areas low yields are also an issue) make the cost of cassava flour considerably higher than that of imported cereals. In the short- to medium-run, however, cassava intra-regional trade for human consumption and animal feed should be a viable option if the impediments are addressed. Additionally, women can benefit significantly from this process because they play a dominant role in food production and trade in Africa.

What do you think should be done to accelerate cassava trade in Africa, if you agree with me that cassava has a great potential to alleviate regional food shortages and poverty?

Sources: Javis, Andy, Is cassava the Answer to African Climate Change Adaptation, CIAT, February 2012; TIPS and AusAID, Trade Information Brief, Cassava; David, Michael, Cassava Inclusion in Wheat Flour, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, February 24, 2012; Weigand, Chad, Wheat Import Projections towards 2050, U.S. Wheat Associates, January 2011; Hanna, Rachid, Cameroon reaps benefits of investment in agricultural research for development, IITA blog, March 2 2012; and Nweke, Felix, Steven Haggblade, and Ballard Zulu, Building on Successes in African Agriculture, recent growth in African cassava, 2020 Vision for Food, Agriculture, and the Environment, April 2004; and Brenton, Paul, Gozde Isik, De-fragmenting Africa, Deepening Regional Trade Integration in Goods and Services, World Bank, 2012.

Join the Conversation