Decades of civil war and political fragmentation have made Somalia one of the poorest countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly seven of 10 Somalis live in poverty, the sixth-highest rate in the region. Poverty is both widespread and deep, and unless appropriate policies are implemented, persistent poverty and vulnerability will impede future economic and social development. Today, Somalia has an opportunity: Following years of sustained effort to re-establish basic economic governance, Somalia may be on the verge of initiating a debt relief process through the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) Initiative. Normalized relations with international financial institutions mean policies can be translated into practice.

To better understand the lives of ordinary Somalis, the World Bank, together with the Somali statistical authorities created the Somali High Frequency Survey (SHFS). This survey covered all accessible regions, interviewing both urban and rural households to gather data on education, employment, security, consumption, and more.

Voluntary video testimonials of Somalis were also recorded to complement the quantitative data and to give a voice and face to these data. The testimonials — with English subtitles — reflect the challenging situation of living in poverty in Somalia. They depict the sense of powerlessness, pain of hunger, stress, and feelings of disappointment. Yet many also expressed hope and optimism for their country and future.

These testimonials inspire continued efforts to finding innovative ways to helping millions like them escape poverty. That’s why our Somali Poverty and Vulnerability Assessment (SPVA) analyzes these data and provides valuable insights about the underlying causes of poverty and the best strategies for fighting it.

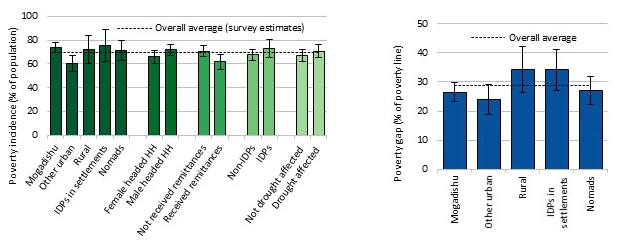

According to the SPVA, almost nine of 10 Somali households are deprived of at least one fundamental dimension: access to income, electricity, education, or water and sanitation. Access to services is particularly limited for the rural population, internally displaced persons (IDPs) and nomads. Despite better conditions in cities, urban populations still struggle with hunger, high absolute poverty (64%), and high non-monetary poverty (41%).

Access to education is low, a situation that threatens to constrain human capital development and economic growth. Cultural preferences in Somalia dictate that children start school later, and nearly 27% of children enrolled in primary school are older than 13 years. Distance from schools is impedes access: For one in three Somali households, schools are at least 30 minutes’ walking distance. Fostering access to education will be essential for breaking the poverty cycle and increasing welfare in the long run.

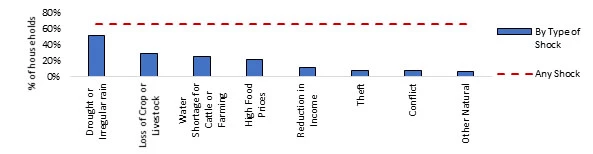

Somali households remain vulnerable to natural, social and economic shocks. In the SHFS data, 66% of Somali households reported experiencing at least one type of shock in the previous 12 months. The most reported shock was drought, as four consecutive seasons of poor rains between April 2016 and December 2017 drastically reduced crop production and harmed livestock. By mid-2017, 6.2 million Somalis experienced acute food insecurity.

Due to an absence of formal insurance, most Somali households are forced to rely on self-insurance to cope with sudden negative occurrences. These strategies include selling, pledging, or mortgaging physical and productive assets, and borrowing from friends, relatives, and money lenders. More robust social safety nets and social protection systems are needed to build risk management and coping capacity of vulnerable households. In 2016, Somalia spent only 0.8% of gross domestic product (GDP) toward social safety nets, roughly half the average in Sub-Saharan African countries.

Recently, massive internal displacement has worsened — mainly due to climate-related shocks — and threatens to further impede development. During the 2017 drought, about a million people were displaced. The SHFS data show that displacement has a very negative effect on well-being. IDPs remain among the most vulnerable: three of four IDPs live on less than $1.90 per day, and half of IDP households experience hunger. IDP settlements tend to be farther from essential facilities such as schools, health centers, and markets, and most IDPs are forced to share essential amenities. Only two in 10 IDPs said they intended to return to their original place of residence.

International remittances represent a critical source of income. Somalia has a large diaspora, and the number of migrants and refugees outside the country reached more than two million, having doubled from 1990 to 2017. Remittances, estimated at $1.3 billion per year, are about the same amount as grants to the government and more than three times total foreign direct investment. The SFHS data underscore the importance of remittances on welfare. Households receiving international remittances are less likely to be poor, increasing — among other things — expenditure on education. Although remittance markets in Somalia remain relatively underdeveloped and costly, the application of mobile technologies may allow the country to leap-frog over intermediate stages of development.

There are ways to improve the situation. Economic growth-creating opportunities will be fundamental for pursuing sustainable poverty and vulnerability reduction. Strategies to create jobs, especially for young Somalis, will be particularly important. Improving service provision for those disproportionately lacking access will be crucial to boosting human capital. Investment in resilience will be needed to prevent livelihood loss for vulnerable rural households, especially due to likely future droughts. Such measures could include agricultural insurance, enabling households to diversify income, and improving access to roads and clean water.

The economic challenges facing Somalia are considerable, but effective, data-driven policies and initiatives can help lead the country toward sustainable development as it starts on a fresh path through the debt relief process.

Join the Conversation