Urban heat mapping by citizen scientists in Cape Town and Buffalo City. Photo: Chris Morgan / The World Bank

Urban heat mapping by citizen scientists in Cape Town and Buffalo City. Photo: Chris Morgan / The World Bank

Originally published March 11, 2024 in South Africa’s Business Day

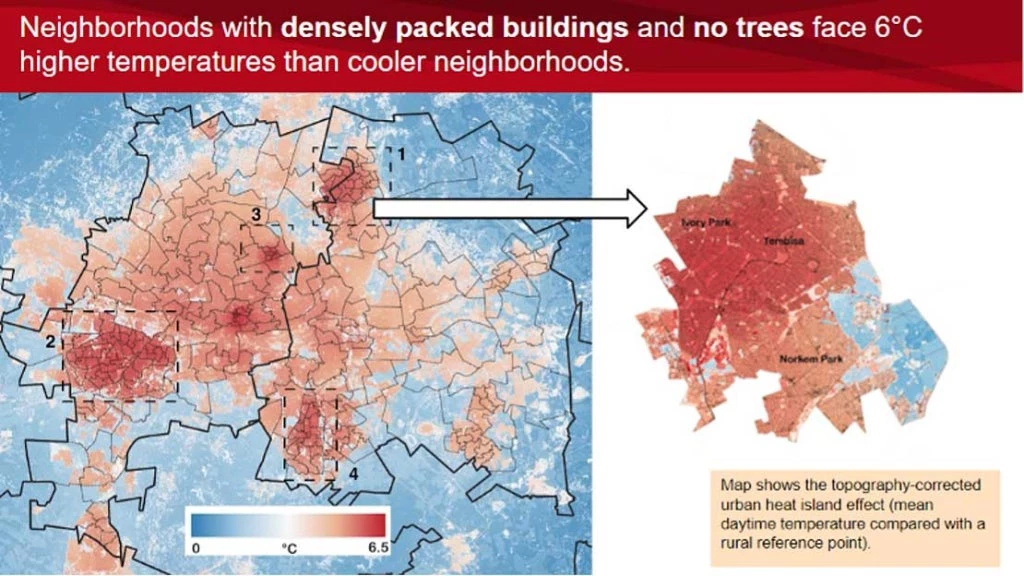

Picture a summer’s day in Alexandra township, in the north of Johannesburg. Tin roofs swelter in the sun. Heat rises between densely packed buildings, and dust swirls on parched, unpaved streets. Residents feel their heartbeats quicken and sweat break on their skin. Trees are few and far between. Even for early risers heading to work, school and daily errands, it’s hard to get respite from the sun’s rays.

Now imagine the scene in the leafy suburbs and cosmopolitan business hub of nearby Sandton. The branches of a jacaranda tree cast generous shade. Breezes circulate along tree-lined boulevards and between widely spaced buildings whose interiors are cool and inviting.

These neighborhoods are a short drive apart, yet on a hot day they feel like different worlds.

The temperature differences, which are partly rooted in apartheid spatial planning, might have been dismissed as an issue of mere ‘comfort’. Unfortunately, air temperatures have already increased by at least one degree Celsius globally because of climate change, and by even more in fast-growing cities where man-made materials absorb and radiate energy from the sun. The result: heat in cities is no longer a matter of comfort, but of survival.

A recent study by the National Treasury Cities Support Programme and the World Bank found that in Johannesburg and Ekurhuleni, most neighborhoods experienced around 20 hot nights per year in recent decades. But Soweto, Alexandra and Tembisa experienced night-time temperatures that were three degrees Celsius higher than the city average. By 2050, these neighborhoods could see as many as 120 hot nights per year.

Temperature increases not only have an impact on the environment but have measurable effects on human health. High night-time temperatures are associated with increased mortality from respiratory, cardio-vascular, and renal conditions because the human body maintains an internal temperature of 37°C partly through rest and cooling at night.

Across South Africa, cities tell a similar story: the climate is getting hotter, yet it is poor and marginalized neighborhoods that suffer most. Historical inequalities - such as legacies of the apartheid era which left some neighborhoods lush and green but others dense and bereft of trees - contribute to these temperature differences. These disparities mean that climate change is hitting the vulnerable hardest.

Fortunately, South Africans are mobilizing to find solutions to extreme heat. Residents of Tshwane, Cape Town and Buffalo City recently took to the streets, to take part in an innovative ‘citizen science’ heat mapping initiative.

The citizen scientists fixed heat sensors onto cars and drove along pre-planned routes across their cities, collecting thousands of temperature measurements. The resulting heat maps will provide crucial information for municipal authorities - which have partnered in this initiative with the National Treasury’s Cities Support Programme, the World Bank’s Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, and the Swiss Secretariat for Economic Affairs - to use when developing heat action plans.

Heat Action Plans save lives. After Ahmedabad, one of India’s hottest cities, experienced 800 excess deaths in one week during the 2010 heatwave, its leaders acted. City authorities now issue yellow, orange or red alerts when temperatures surpass thresholds known to predict illness. The alerts are widely disseminated on television, radio and via social media and are coupled with measures to prevent harm from extreme temperatures in homes, hospitals, streets and workplaces.

Researchers at the University of Washington estimated that the alerts - and accompanying actions such as equipping ambulances with more ice packs, mandating shade and water breaks at building sites, and planting fast-growing urban forests - averted approximately 1,100 hot-season deaths per year.

Encouragingly, cities across the country are developing measures to protect their residents, economies and infrastructure from the impacts of extreme heat. An example is Cape Town, where the city’s own recently approved Heat Action Plan sets out clear measures to help vulnerable citizens stay safe in hot weather.

Will South African cities continue to swelter under heat waves? Global climate change means that unfortunately the answer is yes. But heat waves need not be health crises. By understanding the ‘hidden hazard’ of extreme heat and implementing responses that put the most vulnerable citizens first, South Africa’s cities can lead the world on climate change adaptation.

By setting aside their time and volunteering in the heat mapping campaign, South Africa’s communities are demonstrating their dedication to creating a better life for future generations on a livable planet.

Join the Conversation