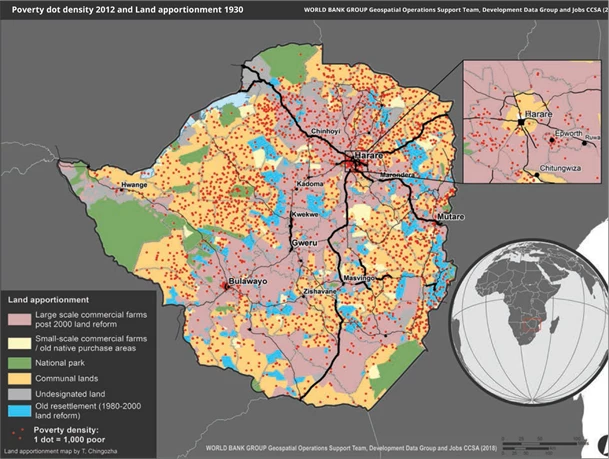

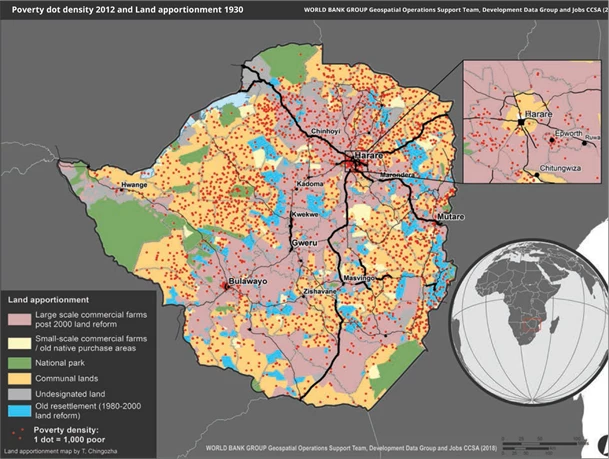

Poverty Density (red dots) and Farmland Type (background color)

Poverty Density (red dots) and Farmland Type (background color)

Zimbabwe has faced hard times since the early 2000s, interrupted by only a brief period of recovery between 2009 and 2012. In recent months, food shortages, high inflation and power outages have reached critical levels. Year-on-year inflation reached a staggering 289% in August 2019. Even though various measures have been taken over the past year or so to enable macroeconomic stabilization., the country is yet to turn the corner. This is in part because Zimbabwe has been hit by multiple shocks such as droughts, foreign exchange shortages and the Cyclone Idai.

Poverty hasn’t decreased in 18 years and recent surveys show that extreme poverty may have even risen by eight percentage points in the last decade. Chronic malnutrition levels remain high and largely unchanged. But the reasons for continued high poverty in Zimbabwe go beyond macro-economic and weather shocks. A recent World Bank report, Spatial Patterns of Settlement, Internal Migration and Welfare Inequality in Zimbabwe, suggests that entrenched poverty is a result of deep rural spatial poverty traps. In 2017, extreme poverty was 13 times higher in rural than urban areas.

What are these spatial poverty traps?

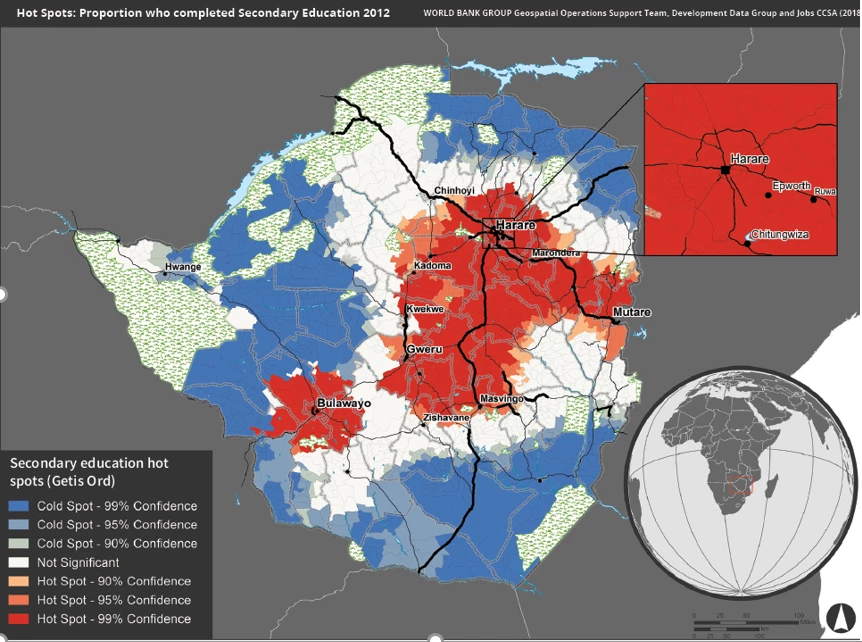

During colonial times, communal areas were designated as locations where African farmers could live and farm while the most productive land were designated for white commercial farmers. A sizeable proportion of the rural population lives in these communal lands that are densely populated and far away from the main road network. They are poorly connected to markets. These areas suffer from the highest poverty rates and the proportion of the extreme poor living in communal lands increased from two-thirds in 2012 to three-fourths in 2017. This was driven by the recent increase in extreme poverty. Map 1 shows the high concentration of the extreme poor in communal lands in 2012. Education levels are typically also lowest here (Map 2) and so are other social outcomes such as access to electricity and improved drinking water.

MAP 1. POVERTY DENSITY (RED DOTS) AND FARMLAND TYPE (BACKGROUND COLOR).

MAP 2. PROPORTION WHO COMPLETED SECONDARY EDUCATION: HOTSPOT ANALYSIS

The fast-track land reform carried out during the 2000s aimed to address this unequal access to productive land, but so far it has not helped enough communal farmers to overcome their poverty traps. Between 2002 and 2012, around 400,000 people moved to commercial farm areas (both urban centers and rural parts) of which around 290,000 came from communal lands and 110,000 from Harare. However, around 140,000 people moved in the other direction: from the commercial farming areas to communal lands. The latter group likely included many farm workers who had lost jobs in the commercial farming areas after the land reform. Between 1999 and 2014, average labor productivity in the agricultural sector fell by 55% according to labor force survey data. Thus far, the fast track land reform has not structurally addressed the spatial poverty traps that are prevalent in Zimbabwe’s rural areas.

Other factors such as poor connectivity are also key. While the communal areas are typically densely populated, they are often located far from good roads. As a result of the colonial legacy, the existing main road network connects the urban centers located in the less populated commercial farm areas, which were built to connect commercial farms to factories and markets rather than people to services. People in communal lands have extreme poverty rates that are five to seven percent higher than those living in other types of farms when controlling for other factors. This reflects the structural lack of economic opportunities in these areas and the deep disadvantages that people face.

What can be done?

Two types of measures for tackling the spatial poverty traps are critical.

First, create policies and stimulate investments to improve connectivity and facilitate integration of these remote communities. This could involve improvements in secondary roads and ICT infrastructure to allow for better movement of goods, services, people, and ideas. In addition, incentives could be created to enable people to move away from areas that are too densely populated - such as better road connections- through the allocation of more resources to road maintenance, with a focus on secondary and tertiary roads. Better housing facilities and an improved investment climate in nearby small towns would also help.

Second, there may be a need to intensify efforts to ensure delivery of social services, such as education and health are of a similar quality and level of affordability in all areas of the country. The government has expanded the use of user fees due to a lack of budget. This has resulted in lower financing for basic services in poorer areas. However, the formula proposed for the transfer of resources to provinces and local governments includes population, poverty severity and land area. This should provide a chance to equalize financing of basic services. Agricultural research and extension services could possibly be better adapted to the needs of communal farmers. Improved data systems for better tracking the progress in well-being across local areas would be a welcome complimentary activity.

Unless these spatial constraining factors are addressed more consistently and structurally, a better quality of life will remain elusive for most Zimbabweans.

World Bank Sr. Economist Stella Ilieva, Lead Agriculture Economist Luc Christiaensen and Sr. Urban Economist Megha Mukim contributed to this blog.

Join the Conversation