The world is in turmoil. The combination of the Japanese earthquake, tsunami and nuclear crisis, the conflict in Libya and the European debt crisis, may change the way we look at the world. Newsweek put it most dramatically last week in its headline: “Apocalypse Now”

The perspective of developing countries is different. They appear to be a beacon of stability in these turbulent times. Africa is set to grow again by more than 5 percent in 2011--for the 7th time in 8 years.

No doubt Africa and other developing countries will be affected by this global turbulence which once again originated in richer economies. Kenya is a case in point. Since the end of 2010 inflation has doubled (although from a low base), the shilling has weakened to its lowest level in 15 years, and the stock market index declined by 10 percent. Many observers are asking if Kenya facing another episode of economic turmoil similar to 2008-09.

Ragnar Gudmundsson from the IMF and I argue that this need not be the case for two main reasons. First, since 2010 a new growth momentum has been building, aided by structural reforms, the new constitution, and a dynamic private sector. Second, Kenya has a strong track record of economic policymaking that has helped it to navigate previous shocks and leaves it well positioned to pass through this storm as well.

The external shocks are real. Food prices have risen but from a lower base because of a good harvest in 2010. More importantly, the rapid increase in oil prices has hit Kenya’s external position. In 2010, the oil price averaged US$ 80 per barrel; by mid-March it reached US$ 115 per barrel. Oil represents almost a quarter of Kenya’s total imports and, according to simulations by my colleague John Randa, $100 per barrel oil will widen the current account deficit by an additional 2 percent (see figure 1)*.

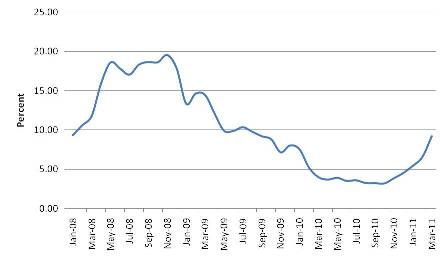

The increase in food and fuel prices led to rising inflation which almost reached 10 percent in March 2011. This is double the end-2010 level but substantially lower than 2008/09 (see figure 2).

FIGURE 1: Kenya’s Balance of Payments deteriorates with higher oil prices

Source: Central Bank of Kenya, World Bank estimates

Figure 2: Kenya’s inflation: Down and up

Source: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics

In the past Kenya has managed external shocks well, especially the global financial crisis. This time should be no different. Ragnar and I suggest four things the government can do to prepare:

First, stand ready to tighten monetary policy further if inflationary pressures persist. It is important to signal Kenya’s commitment to preserve the hard-won gains of low inflation and price stability.

Second, keep the fiscal deficit within current targets. Though still low by international standards, Kenya’s public debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 35 percent in 2007 to almost 50 percent today. The time has come to start rebuilding the buffers that served the country so well in the past two years.

Third, enhance export competitiveness. The best way to start making Kenya more competitive is to modernize the port of Mombasa, East Africa’s most important infrastructure asset.

Fourth, use cash rather than food in responding to food shortages. Kenya can learn many lessons from the 2009 food crisis, including attempts to control food prices that resulted in subsidies going to the rich, while creating opportunities for corruption. By contrast, many countries have successfully implemented cash transfer programs when food prices spiked. Given Kenya's success with 'mobile money', this seems a more effective approach and one that would also help to build a more robust social protection system.

*This analysis will be presented in the next Kenya Economic to be released early June 2011

Join the Conversation