Much has changed in Mozambique since the turn of the century. Today, the typical Mozambican lives 10 years longer than in 2001, largely due to a significant decline in infant and maternal mortality, reduced levels of morbidity across the population and improved access to health care services. Children are now more likely to participate in school than ever before, and the average household has a better chance of consuming safe water and being connected to the electricity grid. More Mozambicans live in better quality dwellings, scroll drown through messages received on their cellphones, and watch football games on flat screen TVs.

This progress has taken place in the backdrop of remarkable growth. Mozambique witnessed one of the fastest growth rates across Sub-Saharan Africa with its gross domestic product (GDP) expanding at an annual average rate of 7.2% between 2000 and 2016. As a result, average incomes have doubled even though fertility rates have remained relatively high.

The shiny face has a tarnished flip side

Progress in Mozambique is evident, but not everywhere. While the poverty rate fell to 48.4% in 2014/15 – down from 60.3% back in 2002/03, poverty and its associated vulnerabilities still remain entrenched. More than four in 10 Mozambicans are stuck in chronic poverty, meaning that they are not only poor but also lack the human and financial capital to break out of the cycle of poverty. Around 80% of the poor reside in rural areas, mostly in the northern and central regions. Furthermore, data for recent years show that more than half of the total growth in consumption, a standard measure of wellbeing, has accrued to the top 20% of wealthiest households, fueling a rise in inequality. Unsurprisingly, the Gini coefficient, a measure used to monitor inequality, rose from 0.47 to 0.56 between 2008-09 and 2014-15.

To be fair, strong growth, along with rising inequality and social exclusion, is not a pattern limited solely to Mozambique. Evidence shows that economic gains are unevenly shared in the early stages of development. Income inequality has leapt in fast growing countries such as China, Cambodia, Vietnam and Sri Lanka as well as in several African countries, including Senegal, Ethiopia and Uganda. While at varying degrees, most of these economies are undergoing a structural transition away from agriculture to rapid urbanization, which provides the leading explanation for rising inequality. Mozambique is also going through this change, which could partially explain the higher levels of inequality.

However, high and rising inequality hurts growth. It undermines education and skills development, economic opportunities and economic and social mobility of disadvantaged groups. Lower human capital, in turn, hampers their labor participation and productivity, undermining their contribution to the overall process of growth. Lack of inclusion also fuels social and political tension. In addition to undermining growth, inequality also slows down poverty reduction. Results from the recently launched report “Strong but not Broadly Shared Growth – Mozambique Poverty Assessment” (Overview Report)” show that the country could have achieved twice as much poverty reduction after 2000 or 1.8 million more people would have escaped poverty, had growth been more equally shared. Rising inequality will not likely be reversed on its own. Curbing it will require policy action.

Rising to the challenge of inclusive growth

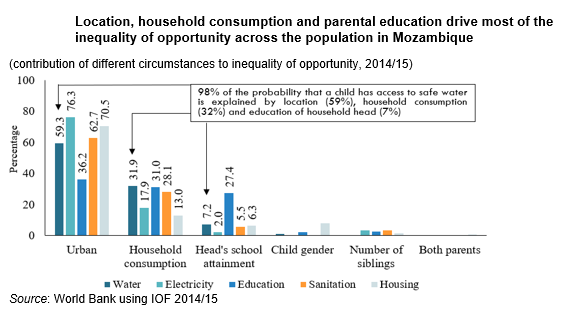

Helping the poor to participate in the growth process and share in its benefits will require investing more in people, starting early in their lives. Our analysis shows that the life trajectories of individuals in Mozambique begin to diverge since the time they are born. Joao, a child born in Maputo, the capital city, has a 60% higher chance to grow up with access to safe water than Bruno, a child born in a rural village near Mocuba in the Zambezia province. Household income and parental education explain another 30% of the gap. Access to other basic services are also unequally allocated across the population. This means that the chances for Bruno to build the human capital he needs to attain a productive life are largely determined by personal circumstances –such as place of birth or the level of education of his parents–which are out of his control.

The challenge of economic exclusion has profound implications for growth going forward. Mozambique largely owes its fast growth in the past to extractive, export-oriented industries with higher value-added but rather weak linkages with the broader economy. More recently, the services sector has begun to play a larger role in the economy but is showing signs of faltering productivity growth. Sustaining economic progress and accelerating poverty reduction in the years to come will require broadening the drivers of growth toward activities with higher productivity and employment potential. But this will be only possible if opportunities are made more equally available for individuals of all backgrounds.

The road ahead: complex but possible

Policymakers in Mozambique have been facing multiple challenges in recent years, including macroeconomic volatility, reduced fiscal space, natural disasters, external risks and, above all, lower growth. Confronting these challenges while ensuring a growth path that yields opportunity and protection for everyone is a tricky balancing act. However, the inability to level the playing field for everyone through inclusive policies will only make the task more difficult. Our simulations show that poverty in Mozambique will fall nearly four times faster if a higher share of Mozambicans –particularly those from the bottom 40%–can contribute to and benefit more from growth. Letting Bruno and others aspire to be doctors, engineers, lawyers or entrepreneurs is not only fair and socially desirable but will ultimately be good for the growth of the country too.

Join the Conversation