In Nigeria, Africa’s largest and most populous country, more women are engaging in work than ever before. By 2011, more than half (57%) of women 15-64 years old were in some form of employment. The increase in women working has been driven by women with the least amount of schooling finding work –these are the women who are more likely to be out of work than those who have had access to more schooling.

This is good news. Jobs for women can be very good “jobs for development” (in the language of the World Bank World Development Report on Jobs) in that they can increase growth now and for the future, give women more control over their lives and those of their children, and foster investment in skills and health of children. Jobs define much of who we are and how we live, and when Nigerian women enter work, they are likely to develop a stronger say in their own destiny. Promoting women’s access to gainful employment can unleash a strong force for innovation, productivity, and economic growth. With income opportunities also comes more control over household resources, and there is evidence that women are more likely than men to invest resources in children’s health and education. This is good for long-term economic growth, as well. All of these changes are needed as Nigeria tries to move towards a more diversified and inclusive economic growth.

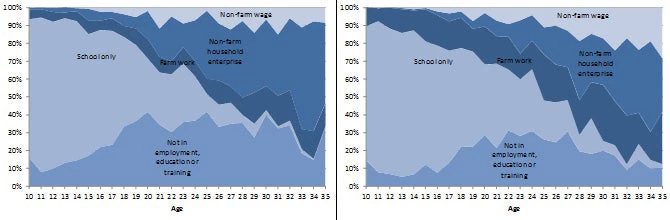

Nigeria nonetheless has some way to go to reap the benefits of a larger female work force. For one thing, as our new report, More, and More Productive, Jobs for Nigeria shows, women’s transition into productive work is still slow in Nigeria. They have less access to both school and jobs; a girl child is less likely to be in school than boys are, and women are still much less likely than men to be working. In fact, in 2011, 17 million adult women were neither working nor studying, and women with low levels of education dominate this group. But moreover, when women do work, they are more likely than men to be in occupations and sectors that pay much less and have lower productivity levels, typically in farming, or work as self-employed or unpaid family workers in non-farm household enterprises. Unlike men, their chances of entering wage work – a job with a salary and an employer which tends to offer the best working conditions in terms of both remuneration and security – does not increase with age. Even when they hold similar levels of education and experience, a Nigerian woman earns less on the job than a man.

Figure 1: Women movement into work, and especially wage work, is slow or incomplete.

Left: Transition to job opportunities, men, aged 10-35

All over the world, women juggle work and family, however, and Nigeria is no exception. Early marriage and family formation plays a role critical role in women’s access to jobs. And it is a very significant issue for young women from poorer households than others. Although girls are more likely to leave school early than boys, they do not then get a job. Instead, young women are much more likely to marry early than men are. At age 20, less than 4% of men are married, compared to about 50% of women in rural areas, And among the poorer families, marriage before age 15 is not infrequent, although 18 years is the legal minimum wage of marriage. With early marriage comes early pregnancies and household responsibilities that effectively remove women from labor market opportunities. Thus, early family formation is associated with both early exit from school and fragmented work opportunities and experience for women. It is also reflected in continued high levels of fertility --Nigeria has a high fertility rate of 5.5 children per women -- and rapid population growth.

Other cultural elements also impact women’s opportunities and either limit access directly or inadvertently encourage informal forms of employment to circumvent laws. Some regulations that are intended to protect women, such as limits on sectors and hours of work, may thus play against women in the work place. Women are also less likely than men to have access to land – land right are not granted statutory protection under land laws and customary land is exempt from succession – which limits their investment and expansion in farming, or in non-farm activities where land can be used as a collateral for credit.

Join the Conversation