Now imagine a situation where Kenya is trading with the whole world, producing world class products and enriching its citizens: consumers can enjoy cheaper products, and exporters exploit expanded opportunities. Given the choice, which scenario would you pick?

A more open Kenya is indeed possible. According to the “Growth Commission”, there have been some 15 economies over the last 50 years which managed to grow at the rate of 7 percent a year for more than 15 years. In doing so they were able to move vast numbers of their citizens out of poverty. These countries have a few things in common, including that they embraced the world economy through trade. Openness to trade encouraged international firms to invest. Over time, local firms caught up and eventually became world leaders, such as Samsung.

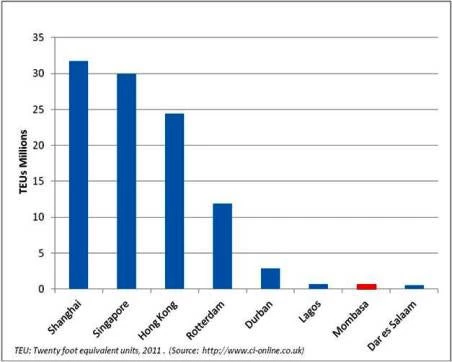

But in order to trade goods, you need efficient ports (and airports). Today, Asia is home to the top nine ports in the world. The most active ports are Shanghai and Singapore, with an annual throughput of more than 30 million containers. Rotterdam is the only non-Asian port in the top ten, but far behind, with some 12 million containers. See figure.

Figure: Shanghai and Singapore handle in a week what Mombasa achieves in a year

No one would have predicted such a scenario twenty years ago. Is there any reason why Africa could not follow suit and, twenty years from now, make it to the top ten? Mombasa would be a natural candidate but there’s a whole lot of catching up to do. Ironically, it is congested despite the small annual volume of 770,800 containers it handles. Kenya’s exports in comparison with global export trade are tiny and many of them, such as flowers and tourists, don’t even enter or leave by sea.

Here are some startling statistics to illustrate the magnitude of the challenge. The volume of goods Mombasa achieves in a year, Shanghai and Singapore handle in about a week. To import a container from Singapore, your goods would spend 19 days on the sea (over 7,500 kilometers), but they would need 20 more days just to make it from Mombasa, by road, to Nairobi. Bringing a container from Tokyo to Mombasa would cost you less than bringing it from Mombasa to Kampala.

Recently, a World Bank team visited the port of Mombasa and a number of companies there. Their stories reflect Kenya’s export challenges. Take AVA (Associated Vehicle Assembly), one of Kenya’s first car assembly plants. AVA could be a prime candidate for international investment to scale-up Kenya’s nascent automotive industry. The reality is bleakly different. High labor costs, expensive and unreliable energy, and delays at the port of Mombasa have constrained the growth of the company. AVA had to close down operations earlier this month for three weeks because components for Mitsubishis and Toyotas were delayed at the port for four full weeks.

The case of AVA provides an important lesson for any growth strategy: While the world is becoming globally integrated, many products are becoming “vertically disintegrated”. Today, few products are being produced in just one place. Instead, subcomponents are manufactured to scale in different locations, and shipped assembled elsewhere. To be integrated in that dense web of trade relations— and to kick start its export engine— Kenya needs to be able to import and export goods in a fast and predictable way. Ports have a big role to play in the efficient flow of goods and their sub-components.

There are no easy solutions. Improving the performance of Mombasa port would require a concerted effort by a large number of players, beyond the Kenya Ports Authority. For example, enhanced management at the port will not bear fruit if off-take through the road and rail networks doesn’t improve as well. Unless antiquated Customs regulations on the disposal of assets are addressed, the port and the container freight stations will remain crowded, with abandoned containers that cannot be auctioned-off.

Yet there are encouraging prospects for change. The dredging of the port is in its final stages and the construction of new terminals is in full swing. Larger ships will be able to dock, cutting shipment costs and Kenya may regain some of the transshipment business it has lost. A state-of -the-art integrated security system and new IT-based tracking being installed will enhance the performance and reputation of the port.

These are steps in the right direction but the pace needs to pick up. Only with a world-class port can Mombasa become a world-class city, benefiting all of Kenya and East Africa. Not so long ago, Shanghai, Singapore and Dubai were poor, sleepy, low-performing coastal cities. Look where they are today.

Many thanks to the World Bank’s transport team for valuable advice, especially Bert Kruk.

Follow Wolfgang Fengler on Twitter: @wolfgangfengler

Join the Conversation