During the last decade the literature on factors affecting corporate default increased exponentially. However, surprisingly little is known about what happens to firms after they default on their bank loans. How many firms are able to overcome the financial distress that led to the default on bank loans? Do these firms regain access to credit? How fast is this process? Which firms have more difficulty in regaining access? In this article, we shed some light on these important questions.

We take the occurrence of defaults as given and analyze what happens to the ability of firms to access credit markets after an episode of financial distress. This is a relevant question, as not all the firms that default on their debts are economically unviable. In many cases, firms default on their liabilities due to unexpected events which do not compromise their economic viability. This question relates closely to the literature on default recoveries but it goes one step further and asks about the ability to borrow again after an episode of financial distress.1

In order to undertake this project we use a unique Portuguese dataset, the Central Credit Register (CRC), which includes data on all loans above 50 euros that were granted during the period 1995-2008. This data is shared by all financial institutions, thus mitigating the traditional asymmetric information problem between lenders and borrowers.

What happens after firms leave default?

There are two main possible outcomes after firms exit default: the firm can become extinct, entering liquidation, bankruptcy or being acquired; or the firm can survive and overcome the financial distress that led to default. Our estimates suggest that the bankruptcy or liquidation rate after default is around 8 per cent, thus showing that most firms are able to overcome a default episode.

For firms that survive, they can either regain access to credit or continue to operate without bank loans (either because they prefer to use alternative funding sources or because banks are not willing to give them credit). We distinguish between two types of re-access: i) broad access; and ii) strict access. In the former case, we consider that the firm has regained access simply if it continues to have access to any bank loans after the default is cleared. In the latter, we consider a stricter access definition and take into account only those cases in which the firm had access to a new loan after default.

Focusing on what happens in the quarter immediately after the firm’s first default episode is resolved, we observe that access rates depend crucially on the access definition we use. In the case of the access, only 13 per cent of firms were able to increase their bank credit in the first quarter after resolving default. With respect to the broad access definition, the numbers are substantially different. In this case, 59 per cent of firms had access to credit in the first quarter after resolving the default. Hence, most firms do not face a long exclusion from credit markets as a penalty for their past defaults.

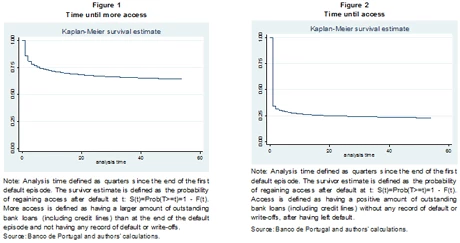

In Figures 1 and 2 we depict the survival functions for the two access definitions. In both cases, most firms regain access almost immediately. For strict access (Figure 1), we observe that firms that regain access are able to do it very soon after the default ended. Access rates are high during the first quarters and then stabilize at very low values. If the firm does not show an increase in bank loans in the first quarters after the default is cleared, it is very unlikely that it will ever. In fact, almost 60 per cent of the firms never regain access to new bank loans.

When the broad definition of access is considered, the results are fairly similar (Figure 2). However, the time of exclusion is even shorter. Most firms are able to regain access immediately. The probability of regaining access decreases dramatically in the second quarter after default ended. Around 25 per cent of the firms never regain access to bank loans. Regardless of the access definition used, we observe that when a firm is not able to regain access soon after the default is cleared, the probability that it will ever be able to becomes very low.

In order to better understand why some firms are able to regain access relatively fast after exiting default, we estimate a Cox proportional hazard model for the time until access. We find that the intensity of the default episode is a key determinant in the process of regaining access: firms that recorded higher credit overdue ratios and higher loss rates take more time to regain access to credit. The impact of default duration goes in the same direction.

The choice of the number of bank relationships also seems to influence how easily firms regain access after default: firms that borrow from more banks take more time to regain access to bank loans. Hence, engaging in single bank relationships may provide some benefits for firms in financial distress. Moreover, firms that defaulted on a larger percentage of existing bank relationships take more time to regain access to credit, which may also be regarded as evidence that more severe default episodes lead to a more prolonged exclusion from credit markets.

When the default occurs with the firms’ main lender, the results are rather mixed: firms that default with their main bank seem to have more difficulties in having access to new loans, but the opposite is seen when the broad definition is considered. This result is probably driven by the way we define strict access. As we observe that most firms actually default with their main lender, the time it takes to regain access may be mechanically driven by this feature of the data.

Finally, we find that firms that exit default during recessions are able to regain access to bank loans sooner. This is an interesting result, as it may suggest that when a firm is able to resolve a default during adverse times, banks perceive this as being a signal of the quality and strength of the firm. In particular, banks possibly consider that these firms are of higher quality (in terms of creditworthiness) and therefore grant credit faster than if the default resolution had happened in non-recession years. Moreover, these firms are more likely to have defaulted due to an exogenous systematic shock than due to idiosyncratic fragilities, thus supporting this creditworthiness assessment by banks.

Another dimension of post-default behaviour that deserves to be explored is whether firms regain access with the banks that were previously lending to them or if they are able to establish new bank relationships. In the quarter immediately after the default episode is cleared, 13 per cent of the firms have access to a new bank loan. From these firms, almost one third obtains that loan from a new bank. These results must be analyzed bearing in mind that the Portuguese Credit Register is designed to be an information sharing mechanism between banks. When a firm defaults on a bank loan, the other banks currently lending to that firm can observe that. Their prospective lenders can also ask to have access to that information, with the firms’ consent, what is usually the common procedure. Notwithstanding this, banks seem to be generally willing to give firms a second chance.

Source: This blog post is a summary of the main findings of Bonfim et al. (2012).

Disclaimer: The analyses, opinions and findings of this article represent the views of the authors, which are not necessarily those of Banco de Portugal, the Eurosystem, the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

Altman, E., B. Brady, A. Resti, and A. Sironi (2005), The link between default and recovery rates: theory, empirical evidence, and implications, Journal of Business 78(6), 2203-2227.

Bonfim, D., D.A. Dias and C. Richmond (2012), “What happens after corporate default? Stylized facts on access to credit”, Journal of Banking and Finance, 36(7), 2007-2025.

Bruche, M. and C. González-Aguadi (2010), Recovery rates, default probabilities, and the credit cycle, Journal of Banking and Finance, 34(4), 754-764.

1 Altman, Brady, Resti and Sironi (2005) or Bruche and González-Aguado (2010) are examples of some relevant contributions to this literature.

Join the Conversation