As economies in the East Asia and Pacific (EAP) region have developed, they have also become important in international financial transactions, both as a source and destination of cross-border bank lending, foreign direct investments (FDI), and portfolio investments. But, as we document in a new paper (Didier et al., 2017), the composition of those financial connections has been changing in recent years in at least two fronts: (i) the partners with which EAP countries interact and (ii) the type of financial transactions conducted.

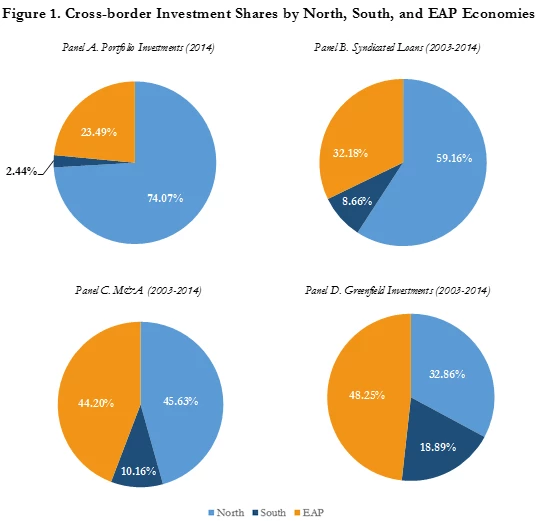

Traditionally, economies in the North (G7 countries, excluding Japan, and 15 Western European economies) have been the most important counterparts of EAP’s inter-regional financial transactions. Although economies in the North still capture the bulk of the region’s inward and outward investments, EAP’s connectivity with the South (non-EAP and non-North economies) has grown relatively faster and has become more relevant for EAP. For example, during 2003-2014, investments to and from the South grew at an annual average rate of 23% for portfolio investments, 30% for syndicated loans, 86% for mergers and acquisitions (M&As), and 9% for greenfield investments. In contrast, cross-border investments involving North economies grew at an annual average rate of 10% for portfolio investments, 14% for syndicated loans, 17% for M&As, and decreased at a 3% in the case of greenfield investments. The rising importance of the South for EAP can be traced to expansions not only in the value of financial connections (intensive margin), but also in the number of active connections (extensive margin).

EAP countries also have strong connections with themselves. That is, other EAP economies are important sources and destinations of EAP’s cross-border financial investments. Although EAP economies are more financially integrated with global markets than with regional ones, intra-regional investments are actually larger than those with the South and, in the case of FDI, they are as large as those with the North. Moreover, EAP stands as the most regionally integrated region in both the intensive and extensive margins when compared to Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe and Central Asia, South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Middle East and North Africa.

Another notable feature of the EAP’s international financial integration is the differences in how it connects with different types of countries. EAP economies are relatively more connected intra-regionally and with the South via FDI, whereas they are more connected with the North in arm’s length investments (portfolio investments and syndicated loans). These existing differences in financial integration patterns across investment types can be related to the relatively less developed financial markets in EAP and the South vis-à-vis those of the North.

Differences in the degree of financial and economic development can also help explain the heterogeneous financial integration patterns across EAP economies. The more developed EAP economies (as measured by their GDP per capita) integrate in a way that is similar to that of the North (having a larger role in EAP’s arm’s length investments), whereas less developed EAP economies integrate more similarly to South economies (having a larger participation in EAP’s FDI financing). For example, during 2003-2014, developed EAP economies accounted on average for 92% of the EAP’s inter-regional syndicated loans, whereas this share was only 47% in the case of greenfield investments. The rest was captured by the less developed EAP economies. Similarly, the more developed EAP economies accounted for 71% of EAP’s intra-regional portfolio investments, but only for 49% of intra-regional greenfield investments.

Recent trends come with benefits but also possible risks. On the one hand, EAP can benefit from greater financial diversification, which would reduce concentration and dependence on North economies. Moreover, as far as economies in the region are more familiar with the institutions and culture of other EAP economies, greater regionalization could foster financial inclusion by serving smaller and less informationally transparent segments. On the other hand, EAP could also bring imported volatility from the newly connected economies. In addition, the increasing regionalization would imply a higher exposure of an economy to shocks originating within the region and a faster spread of foreign shocks once they hit an economy within the region.

Furthermore, to the extent that financial institutions in the South and in EAP are less tightly regulated than those in the North, latest developments can affect negatively the stability of the overall financial system. Therefore, a call for more intensive cross-border cooperation would be desirable for global financial stability.

Differences across financial instruments suggest that, as EAP continues growing and becoming richer, its patterns of financial integration will resemble more those of the North, with less relative emphasis on FDI and more on portfolio and bank investments. Although this type of arm’s length financing arises naturally in more developed countries and is a conduit for more sophisticated transactions, it can have an impact on financial stability, as FDI is perceived to be more resilient when negative shocks occur.

Source: Didier et al. (2017).

Note: This figure shows the share of North, South, and EAP economies in the total value of EAP's cross-border financial investments (considering investments with the North, the South, and with itself).

Reference:

Didier, T., R. Llovet, and S.L. Schmukler, 2017. “International Financial Integration of East Asia and Pacific.” Journal of The Japanese and International Economies 44: 52-66. Working paper available as World Bank Policy Research Paper 7772.

Join the Conversation