Stacks of banknotes under an umbrella | © shutterstock.com

Stacks of banknotes under an umbrella | © shutterstock.com

Deposit Insurance is a key factor in maintaining the stability and resilience of financial systems. This form of financial regulation has been extensively used in history, around the world, and during the 2008 financial crisis. Despite notable theoretical work in this area, there is a limited number of empirical studies exploring the behavioral consequences of deposit insurance on depositors. The reason is that changes in deposit insurance usually happen in times of financial turmoil, and it is difficult to obtain high-frequency data from bank accounts. Our work aims to answer a simple question: does deposit insurance affect deposit behavior? If so, by how much?

This issue is particularly important because depositors’ responses to deposit insurance may alter the level of savings in bank accounts, which in turn affects the provision of credit and therefore investment. If we consider deposit insurance as creating a safe asset, low levels of deposit insurance in medium-to-low-income countries may explain their low levels of formal savings.

We study the effect of an unexpected change in deposit insurance in Colombia on depositor behavior, using unique data on monthly deposits from a large Colombian bank, covering more than 50,000 individuals between 2016 and 2018. We also present the results from a survey of the bank's customers to uncover which assets were liquidated in the aftermath of the policy change. The literature on the subject has focused on banks’ moral hazard and not on depositors for two main reasons. First, accessing depositor-level information is difficult, as financial institutions are not obliged to disclose such data by regulators. Second, most changes in deposit insurance take place during periods of financial turbulence, and as a result, separating the effect of deposit insurance from concurrent economic shocks is challenging.

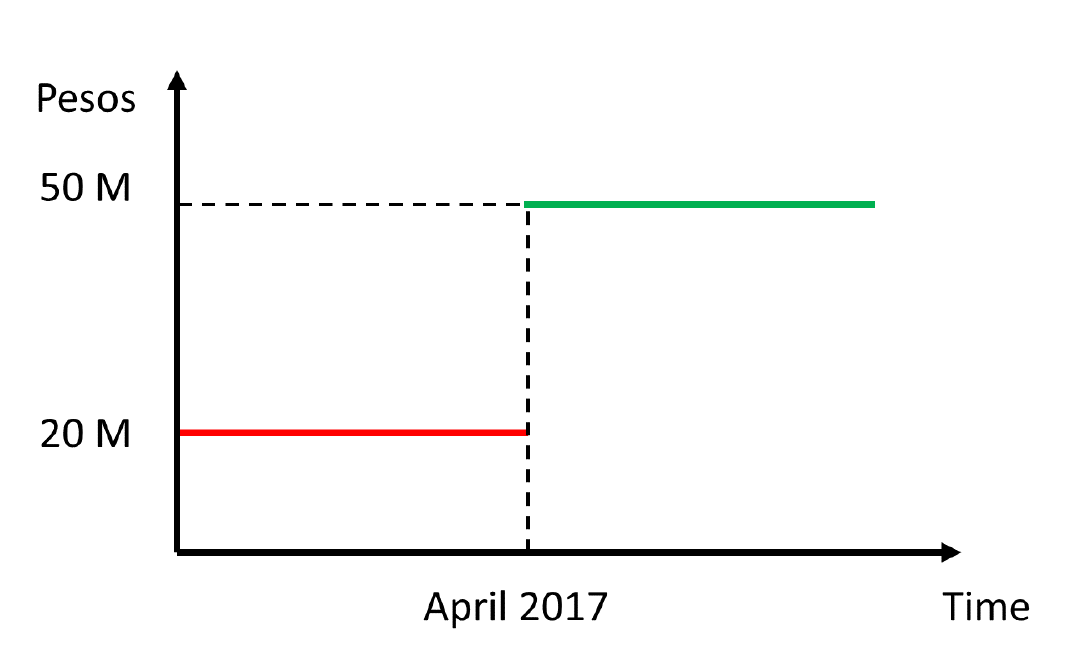

Our work studies the effect of deposit insurance on depositors exploiting an unexpected policy change (illustrated in Figure 1). On April 18, 2017, the Colombian deposit guarantee fund (Fondo de Garantías de Instituciones Financieras) increased the insurance for individual deposits from 20 million Colombian pesos (COP) (approximately 6,780 USD at the average exchange rate of 2017 of around 2,950 COP/USD) to 50 million COP (around 16,950 USD). The change was unexpected and the announcement to the public took place only one day after its implementation. Contrary to most changes in deposit insurance, which happen during financial crises, this increase aimed to update the real value of the insurance threshold, which had not been changed since 2000.

Our identification strategy combines this increase in time with a measure of cross-sectional exposure at the depositor level. We assign individuals to one of four bins according to their average monthly deposits before the policy change. Bin 1 includes depositors with average deposits between 5 million and 20 million COP, and who were therefore fully insured before the policy change. Bin 2 includes individuals with 20 million to 50 million COP and who were partially insured before the change and completely insured after the policy change. Individuals in Bins 3 and 4 have pre-policy deposits above 50 million COP and are therefore never fully insured. Using a difference-in-differences design, we study the differential response of individuals in each bin to the policy change.

Figure 1 — Timing of the Policy Change

Our results indicate that deposit insurance has a causal effect on deposits (see Figure 2). We find that while depositors across different bins were on parallel trends before the policy change, those who were fully insured (Bin 1) and nearly fully insured (Bin 2) respond to higher insurance by increasing their relative level and growth rate of deposits.

Figure 2 — Event Study Design

Notes: The y-axis reports the coefficients of the effect of the policy change on the log of deposits, for each bin. The x-axis reports the corresponding lead or lag, where 0 corresponds to May 2017. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

The following are our three main findings. First, a descriptive analysis shows that depositors were bunching below the 20 million COP insurance threshold before the policy change. In particular, we observe that an extensive mass of individuals held deposits of between 15 million and 20 million COP. Second, an event-study specification indicates that the trends of deposits across Bins 1, 2, 3, and 4 were parallel before April 2017. However, in the 12 months following the policy change, deposits expanded significantly more for individuals who were completely insured before the policy change (Bin 1) and for those who were nearly fully insured and became fully insured after April 2017 (Bin 2). Relative to individuals in Bin 3, the response of individuals in Bin 1 corresponds to increases of 7% in the level of deposits and 1.5% in the rate of deposit growth. Individuals in Bin 2 increased their level of deposits by 5.3% and deposit growth by 0.4%. Those in Bin 4 do not show any change in the level or growth rate of deposits. Our results endure a battery of robustness tests and indicate that individuals below the old policy threshold responded with a higher increase in deposits.

Third, in the paper, we leverage the cross-sectional heterogeneity in the exposure to the treatment to estimate an elasticity of deposit growth to deposit insurance of 0.4 point. This point estimate is close to the elasticity of 0.6 that we obtain in a similar exercise exploiting the 2008 threshold increase in the United States, which may be higher due to other events that occurred during the financial crisis. Finally, the results from a survey on 990 clients in our sample indicate that an important fraction of bank clients knows about deposit insurance and changed their asset holdings (cash in particular) to increase deposits. This result is suggestive of a change in asset composition in response to the policy change.

All in all, we believe that this paper offers important insights into the effects of deposit insurance for three reasons. First, the policy change we consider provides the opportunity to isolate the effect of deposit insurance, unconfounded from the factors that are common in periods of crisis or financial distress. Second, the paper quantifies the elasticity of deposit growth to deposit insurance, which can be useful for theoretical and empirical researchers, policy makers, and bankers. Third, our work contributes to a growing literature at the intersection between banking and development economics, showing that financial regulation can promote the size and depth of financial systems and credit markets.

Join the Conversation