CNN Anchor Erin Burnett mocked the Occupy Wall Street protest during her show recently. Burnett asked a protester if he knew taxpayers “actually made money” on the Wall Street bailout. The protester responded that he was “unaware.”

“Yes, the bank bailout made money for the taxpayers, right now to the tune of $10 billion,” Burnett said. “These are seriously the numbers. This is the big issue? So…we solved it.”

As that exchange demonstrates, the bailout was a success or a failure depending on how you look at it. If you look at direct cash expenditures and receipts, the government has broken even or perhaps made a profit. But that doesn’t seem correct to many. Intuitively, many people from across the political spectrum have a strong suspicion that there are other costs that are not being captured by direct dollar figures.

The problem is that people don’t have a ready way to quantify what they know intuitively—that the implicit guarantee provided by the government has value, and bailouts lead to excessive risk taking and moral hazard and, ultimately, future costs for taxpayers. So instead, the focus shifts to direct measures of simple cash dollars, making the bailout appear to be a surprising success.

A recent Washington Post article stated that the bank bailout “officially turned a profit for taxpayers…Treasury invested $245 billion [and] $251 billion has now been returned to government coffers.” While the article cautioned that “TARP could leave a legacy of ‘moral hazard” no attempt was made to incorporate moral hazard costs into the headline numbers.

Recently, another article in the Wall Street Journal cited government claims that “TARP has been a success” because it is “being paid back at an apparent profit for taxpayers.” But the article then cautioned that “the focus on repayment fails to consider the huge taxpayer costs [that] … dwarf the size of TARP.” As the article explained, “Seldom mentioned are future costs resulting from using TARP funds to rescue systemically important financial and other firms,…solidifying the market’s belief in an implicit guarantee from the government.” They cautioned that the implicit guarantee “need[s] to be included in any accounting of the costs of TARP.”

In a recent paper with my colleague Joe Warburton, we investigate and try to quantify the price tag associated with the implicit guarantee provided by the government to systemically important banks. Using credit spreads on bonds issued by large U.S. financial institutions, we find that expectations of state support reduce the cost of debt for these systemically important institutions.

While there is a positive relationship between the cost of debt and risk for most financial institutions, this relationship breaks down for the largest financial institutions. Debt holders of major financial institutions have an expectation that the government will shield them from losses and, as a result, they do not they do not internalize the full cost of the risk presented by these institutions.

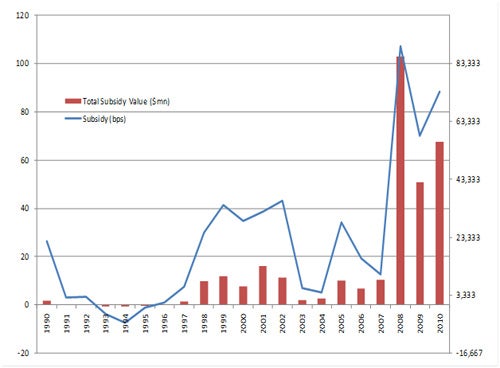

This expectation of public support constitutes a subsidy to large financial institutions, lowering their funding costs. As illustrated in the chart below, we find that the implicit subsidy given to large banks provides an annual funding cost advantage of approximately 16 basis points before the financial crisis (from 1990-2007), increasing to 88 basis points during the crisis (2008-2010), peaking at more than 100 basis points in 2008. The total value of the subsidy amounted to about $4 billion per year before the crisis, increasing to $60 billion during the crisis, topping $84 billion in 2008.

Implicit state insurance represents a significant wealth transfer from taxpayers to major financial institutions. Compared to this transfer of wealth, the accounting profit of $10 billion reported above looks rather paltry. We believe that the cost of this implicit insurance should be internalized by imposing a corrective insurance premium, thereby restoring bondholders’ incentive to monitor banks and creating a more stable and efficient financial system.

You can find our paper, ‘The End of Market Discipline? Investor Expectations of Implicit State Guarantees’, here.

Join the Conversation