Adding coins into a piggy bank | © shutterstock.com

Adding coins into a piggy bank | © shutterstock.com

A vast number of policies aiming to increase savings are currently in place, with many of them involving nudges. These policies are based on the assumption that savings are financed with decreases in consumption. However, when policy makers or researchers evaluate these interventions, they often focus on immediate savings outcomes without looking at where the money comes from, even though a non-trivial fraction of households hold liquid savings while simultaneously carrying credit card debt (the so-called credit card debt puzzle). Understanding whether or not increases in savings are financed with high-interest debt is of critical importance for policy makers and researchers alike because if they are, consumers may end up worse off than when they started.

In a recent working paper, we investigate whether or not saving nudges lead to increases in credit card borrowing. We use data from a large-scale field experiment paired with comprehensive and accurate panel data on individual bank accounts and credit cards. The data originated from a bank in Mexico, Banorte, which ran a randomized experiment with 3,054,438 customers. Of these, 2,679,545 customers were treated with weekly or bi-weekly ATM and SMS messages encouraging them to save for 7 weeks during fall 2019, while the remaining 374,893 customers received no messages.

We pay particular attention to the borrowing response of individuals with the largest predicted response to the nudge. For them, potential unintended consequences of saving nudges are all the more likely. To identify them, we predict treatment effects at the individual level with a causal forest. The causal forest allows us to avoid the over-fitting problems we would inevitably encounter if we manually searched for subpopulations with large treatment effects. A manual search would misleadingly attribute large treatment effects to subpopulations in which some observations show unusually large savings due to idiosyncratic shocks that could affect borrowing outcomes as well. In contrast, the causal forest is based on a repeated split-sample procedure, in which one sample is used to partition the covariate space and another is used to estimate the corresponding treatment effects. This eliminates the possibility that pre-treatment covariates predict a large treatment effect due to idiosyncratic shocks that could also affect other outcomes, including borrowing decisions.

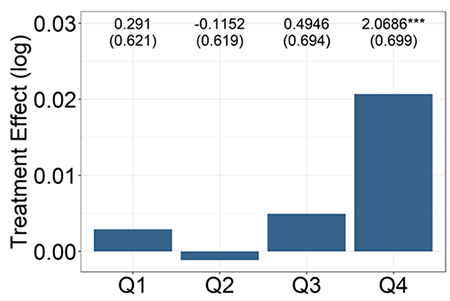

In figure 1, we split individuals into quartiles of predicted treatment effects resulting from the causal forest and calculate the actual treatment effects for each group. In essence, the forest identifies two groups of individuals: a large first group with a zero treatment effect (quartiles 1 to 3 of the predicted treatment effects), and a smaller second group with positive and significant treatment effects (the top quartile of the predicted treatment effects).

Figure 1. Treatment effect on checking account balances, as a function of predicted treatment effects at the individual level

Notes: Individuals are split into quartiles of predicted treatment effects on savings, based on the score generated by the causal forest.

We then focus on individuals in the top quartile of the predicted treatment effects, and among them, we look at the saving and borrowing response of individuals who have a credit card. We find a 6.1% increase in savings, from a base of 31,702 MXN (3,392 USD) in the control group (1 MXN = 0.107 USD PPP). This represents an increase of 1,948 MXN (208 USD). As shown in Figure 2, we rule out that these increased savings were mirrored by an increase in debt, as we find a nonsignificant effect on credit card borrowing. Figure 2 also shows a similar pattern for individuals who had a credit card and paid credit card interest at baseline, or who had a credit card and have substantial credit limit available on their credit cards.

Figure 2. Treatment effects on checking account balances, credit card balances and credit card interest, for individuals in the top quartile of predicted treatment effects on savings, according to the causal forest

Notes: Blue bars consider all individuals with a credit card. Gray bars consider individuals with a credit card who paid credit card interest at baseline. Black bars consider individuals with a credit card who keep their credit line utilization below the median. Standard errors in parenthesis. *, ** and *** denote significance at the 10, 5 and 1 percent level.

We subsequently document two more findings. First, spending decreases, as measured by ATM withdrawals and expenses with debit and credit cards, in response to the savings nudge. Second, individuals who carried credit card debt at baseline do not use their new savings to pay off existing debt. The latter finding implies that the savings nudge exacerbated the simultaneous holding of low-interest savings and high-interest debt. In our sample, the average credit card interest rate is 35.2% and checking accounts pay 0% interest. Despite the large price differences, 13.5% of individuals who pay credit card interest keep balances higher than 50% of their income in their checking accounts (minimum balance observed over the 6 months previous to the intervention). Furthermore, almost 50% of individuals in the co-holding group are also in the top quartile of predicted treatment effects from the nudge.

We thus ask whether our main findings, that savings nudges reduce consumption rather than increase borrowing, are informative about the leading explanations of the co-holding puzzle. We argue that variants of models based on mental accounting are likely to predict a null effect on debt from an exogenous increase in savings. By keeping savings in a separate mental account, individuals effectively remove a certain amount of money (labeled as savings) from their consumption-borrowing problem. Therefore, individuals reduce consumption rather than increase borrowing when they allocate whatever resources they have left. In contrast, in models without mental accounting, the future availability of money exogenously set aside for savings (via the saving nudge) should be considered in the consumption-borrowing problem. In this case, the total amount of resources available for consumption did not change. So, individuals borrow against future resources, leaving their consumption levels unchanged.

In summary, we find that savings due to nudges are not financed with new debt, but with reductions in consumption . Nudges lead to net increases in savings regardless of preexisting levels of debt. For some individuals, this may be second best, since they may be better off paying existing debt. We argue that the reason for that is that people process saving and borrowing decisions in different mental accounts.

Join the Conversation