Microcredit has become a buzzword over the past couple of decades and many have hoped that small loans would help microenterprises grow and raise the incomes of their owners. Recently, a number of rigorous studies have measured the effect of credit on microenterprises. The results paint a nuanced picture; with most studies showing no strong impact on microenterprise growth (see Chapter 3 of the World Bank Group’s Global Financial Development Report 2014 for a summary of these findings).

Researches have uncovered several reasons why microcredit may not lead to the expected increase in firm growth. For example, to mitigate default risk, microloans often have joint liability. However, joint liability may discourage investment because group members have to pay more if a fellow borrower makes a risky investment that goes bad, but they do not enjoy a share of the profits if the investment yields returns. Also, looking beyond microcredit, recent studies suggest that providing other financial instruments, such as savings products and microinsurance, can spur microenterprise investment and growth.

To address the shortcomings of traditional microcredit, some commercial banks have started to rely on innovative approaches for providing financial services to microentrepreneurs. Together with my colleague Inessa Love, I studied the case of Banco Azteca in Mexico. In October 2002, this bank simultaneously opened more than 800 branches in all of the existing stores of its parent company, a large retailer of consumer goods, Grupo Elektra. Unlike many microfinance institutions, Banco Azteca is a for-profit operation that is supervised by the financial sector regulator. Launching Banco Azteca thus required an enabling regulatory environment that allowed opening bank branches in the retail locations.

Banco Azteca provides savings accounts and is able to make individual liability microloans by relying on synergies with the large retail chain. Since the bank branches are located inside retail stores they share the costs of the distribution network. To mitigate risk, Azteca draws on a large database that the retail chain has accumulated on customer repayment behavior on installment loans. Banco Azteca’s financial products are particularly attractive for informal businesses that lack the documentation necessary to obtain traditional bank loans. Azteca requires less documentation than traditional commercial banks, often accepting collateral and cosigners instead of documents.

Inessa and I use a difference-in-difference strategy based on the predetermined locations of Banco Azteca branches to identify the causal impact of their opening on economic activity. We compare the changes in the employment choices and income levels of individuals before and after the branch openings across municipalities with or without Grupo Elektra stores at the time of the branch openings. We control for the possibility that time trends in outcome variables may be different in municipalities that had Grupo Elektra stores and those that did not have these stores.

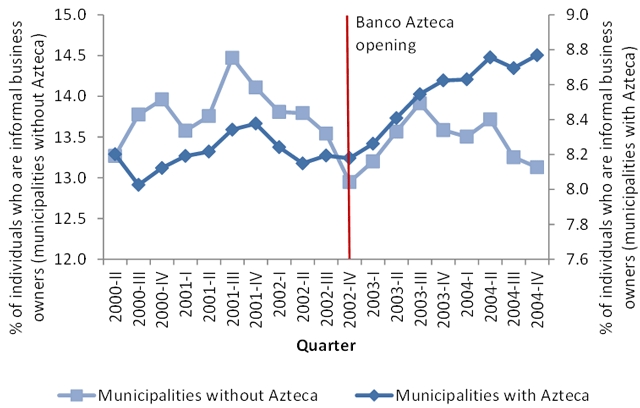

Figure 1: Individuals Who Work as Informal Business Owners in Municipalities with and without Banco Azteca over Time

Our results show that the branch openings led to a 7.6 percent rise in the proportion of individuals who run informal businesses, which is consistent with Azteca’s flexible documentation requirements. Figure 1 illustrates that the proportion of informal business owners followed a similar pattern across municipalities and across time before the branch openings. After the branches opened, the proportion of informal business owners rose substantially in municipalities with branches, but, on average, remained similar to the initial levels in municipalities without the new branches. We also find that the branch openings led to an increase in employment by 1.4 percent and an increase in income levels by 7.0 percent (a more detailed discussion of our study and results is featured in Chapter 3 of the Global Financial Development Report 2014).

Because Banco Azteca provides both small loans and saving accounts, we cannot disentangle whether its positive effects on entrepreneurial activity, employment, and income are due to credit or savings. Another feature of Banco Azteca is that it offers consumption loans. Thus, in addition to providing financial services to microentrepreneurs, it boosts the purchasing power of potential microenterprise clients, which may promote firm growth.

Overall, however, our findings suggest that increased access to financial services does promote microenterprise activity and growth. In fact, our measured impacts of Banco Azteca are larger in municipalities that were relatively underserved by the formal banking sector before Azteca opened (measured by demographic data on bank branch penetration). This result provides additional evidence that the channel through which Banco Azteca exerts an impact on economic activity is the expansion in access to financial services.

Further Reading

Bruhn, Miriam and Inessa Love. “The Real Impact of Improved Access to Finance: Evidence from Mexico”. The Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Join the Conversation