How should the relative importance of banks and stock markets change as countries develop? Is there an optimal financial structure—in other words, should the mixture of financial institutions and markets change to reflect the evolving needs of economies as they develop?

Previous research has found that both the operation of banks and the functioning of securities markets influence economic development (Demirguc-Kunt and Maksimovic, 1998; Levine and Zervos, 1998), suggesting that banks provide different services to the economy from those provided by securities markets. Indeed, banks generally have a comparative advantage in financing shorter term, lower risk, well collateralized investments, while arms length markets are relatively better suited in designing custom financing for more novel, longer run and higher risk projects.

However, economic theory also emphasizes the importance of financial structure, i.e., the mixture of financial institutions and markets operating in an economy. For example, Allen and Gale’s (2000) theory of financial structure and their comparative analyses of Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States suggest that (1) banks and markets provide different financial services; (2) economies at different stages of economic development require different mixtures of these financial services to operate effectively; and (3) if an economy’s actual mixture of banks and markets differs from the “optimal” structure, the financial system will not provide the appropriate blend of financial services, with adverse effects on economic activity.

Empirical research, however, has been largely unsuccessful at clarifying the evolving importance of banks and markets during the process of economic development. In our earlier research Ross Levine and I show that banks and securities markets tend to become more developed as economies grow and that securities markets tend to develop more rapidly than banks (Demirguc-Kunt and Levine, 2001). Thus, financial systems generally become more market-based during the process of economic development. But this pattern could simply reflect supply side factors, such that securities markets grow more rapidly than banks as economies expand, with no implication that firms and households change their relative demand for the services provided by banks and markets respectively.

In a recent paper with Erik Feyen and Ross Levine, we try to evaluate empirically the changing importance of banks and securities markets as economies develop. In particular, we focus on assessing whether economies increase their demand for the types of services provided by securities markets relative to the services provided by banks as countries grow. We do this by testing whether the economic development “returns” to improvements to both bank and securities market development change as economies grow. At a more exploratory level, we also examine whether each level of economic development is associated with an “optimal” financial structure, such that deviations from this optimum are associated with lower levels of economic activity. We use data on 72 countries, over the period from 1980 through 2008, and we aggregate the data in 5-year averages (data permitting), so that we have a maximum of six observations per country. We use several measures of bank and securities market development, including standard indicators such as bank credit to the private sector as a share of gross domestic product (GDP), the value of stock market transactions relative to GDP, and the capitalization of equity and private domestic bond markets relative to GDP.

The primary methodological contribution of this paper is using quantile regressions to assess how the sensitivities of economic activity to both bank and securities market development evolve as countries grow. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions provide information on the association between, for example, economic development and bank development for the “average” country, the country at the average level of economic development. But quantile regressions provide information on the relationship between economic activity and bank development at each percentile of the distribution of economic development. Thus, we assess how the associations between economic development and both bank and securities market development change during the process of economic development.

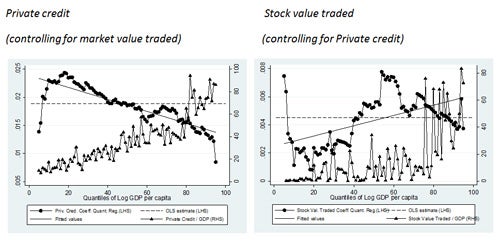

Figure 1 illustrates our findings. In Figure 1 the graph on the left side plots the coefficients from quantile regressions for each of the 5th to 95th percentiles of Log Real GDP per capita, where the dependent variable is Log Real GDP per capita and the main regressor is Private credit and we also control for Stock value traded. A circle indicates each coefficient estimate.

Figure 1. Quantile coefficients for private credit and securities market activity (Click on the image to view a larger version.)

The left axis provides information on the values of the coefficient estimates. Thus, the estimated coefficient, indicated by a circle, depicts the “sensitivity” of Log Real GDP per capita associated with a change in Private credit at each percentile of economic development. The graph also plots the actual value of Private credit at each percentile. A triangle indicates these actual values, where the scale is provided on the right axis. The triangles provide the average “quantity” of Private credit at each percentile of economic development. In the graph on the right, we provide similar information on the relationship between economic activity and Stock value traded. In both figures, the horizontal dotted line is the OLS estimate of the coefficient on the financial development indicator. The solid lines are the estimated linear relationship between the sensitivity coefficients and log GDP per capital.

In terms of bank development, Figure 1 shows that as Log Real GDP per capita rises, two things happen: (1) Private credit rises (triangles) and (2) the marginal increase in Log Real GDP per capita associated with an increase in Private credit falls (circles). Put differently, quantities rise and sensitivities fall. This relationship is also statistically significant: as economic activity increases, there is a significant reduction in the sensitivity of Log Real GDP per capita to an increase in Private credit.

The results are different for securities market development. As Log Real GDP per capita rises, (1) Stock value traded rises and (2) the marginal increase in Log Real GDP per capita associated with an increase in Stock value traded also rises. That is, quantities and sensitivities rise. This effect is also statistically significant: the sensitivity of economic activity to Stock value traded increases as Log Real GDP per capita rises.

These results suggest that the relationship between bank development and economic activity differs from that between securities market development and economic activity. As economies develop, the marginal increase in economic activity associated with an increase in bank development falls, while the marginal boost to economic activity associated with an increase in securities market development rises. These results suggest that the demand for the services provided by securities markets increases relative to the demand for those provided by banks as economies develop.

We also conduct a preliminary examination of whether deviations of a country’s actual financial structure from our estimate of the country’s optimum are associated with lower levels of economic activity. To estimate the optimal mixture of banks and markets for each level of economic development, we first regress a measure of financial structure (such as the ratio of bank to securities market development) on GDP per capita for the sample of high-income OECD countries, while controlling for key institutional, geographic, and structural traits. The maintained hypothesis is that conditional on these traits, the high-income OECD countries provide information on how the optimal financial structure varies with economic development. We then use the coefficients from this regression to compute the estimated optimal financial structure for each country-year observation for all countries. Next, we compute the Financial structure gap, which equals the natural logarithm of the absolute value of the difference between the actual and the estimated optimal financial structure, controlling for systematic variation in the prediction errors. The Financial structure gap measures deviations of actual financial structure from the estimated optimum, where larger values indicate bigger deviations, regardless of whether the deviations arise because the country is “too” bank-based or “too” market-based.

We find that deviations of an economy’s actual financial structure from its estimated optimum—i.e., increases in the Financial structure gap—are associated with a reduction in economic output. Even when controlling for bank development, securities market development, country characteristics, and country fixed effects, there is a negative relationship between the Financial structure gap and economic activity. Although we do not identify a causal impact of financial structure on economic development, these results are consistent with the view that the mixture of banks and markets—and not just the level of bank and market development—is important for understanding economic development.

Why is this relevant for policy? This research suggests that we expect the optimal mixture of institutions and markets to change as economies develop. So, the costs of policy and institutional impediments to the evolution of the financial system can be significant. We don’t know enough to target a given financial structure for a particular country. However, if we do see that market or bank development is too skewed compared to what we would expect, these findings give us a reason to dig much deeper. We can try to find out if taxes, regulations, legal impediments or other distortions are leading to excessive reliance on banks or markets. Hence this research can justify a more focused, in-depth investigation of particular characteristics of the financial system that might be hindering economic progress.

References:

Allen, F., Gale, D. 2000. Comparing Financial Systems. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Maksimovic, V. 1998. “Law, finance, and firm growth”. Journal of Finance 53, 2107-2137.

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Levine, R. 2001. Financial Structures and Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Comparison of Banks, Markets, and Development. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Levine, R., Zervos, S. 1998. “Stock markets, banks, and economic growth”. American Economic Review 88, 537-558.

Further Reading:

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Feyen, E. and Levine, R. 2011. “The evolving importance of banks and securities markets.” Policy Research Working Paper No 5805.

Join the Conversation