Words, words, words: do they matter in finance? And, more to the point, do reports on financial stability have an impact on, say, financial stability? New research suggests that the answer is a qualified “yes”: such reports can actually have a positive link with financial stability, if they are done well. Reports that are written clearly, are consistent over time, and cover the key risks to stability are associated with more stable financial systems.

Publishing reports on financial stability has been a rapidly growing industry, with more and more central banks and other agencies around the world now publishing such reports. As of early 2012, around 80 such reports are being issued on a regular basis (Figure 1). The stated aim of most of these reports is to point out key risks and vulnerabilities to policy makers, market participants, and the public at large, and thereby ultimately helping to limit financial instability.

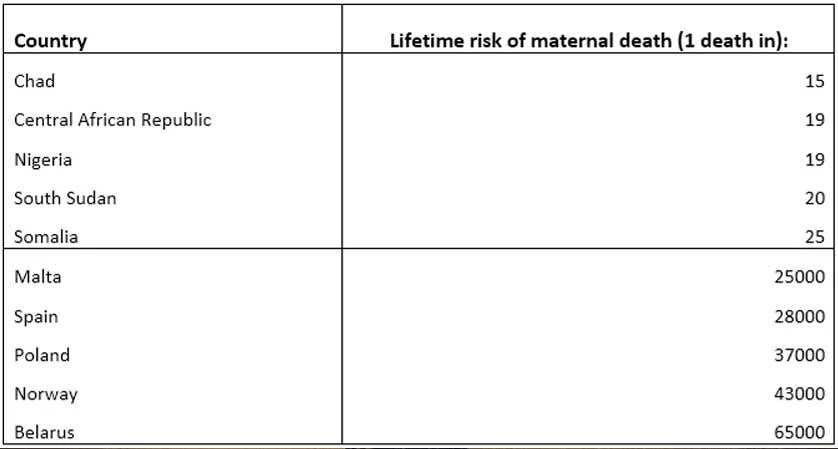

Figure 1. The number of countries that publish financial stability reports

Source: Čihák, Muñoz, Teh Sharifuddin, and Tintchev (2012).

Do these reports actually have an impact? That’s not easy to say. Of course, one can point out that the country where the late 2000s global financial crisis started had no such financial stability report, at least not until very recently. But many of the countries that publish stability reports had their own share of financial problems (Iceland and Latvia are just two of many examples). Indeed, empirical reviews of the experience with financial stability reports have been mixed. Early studies on the subject (Čihák, 2006; Oosterloo, de Haan, and Jong-A-Pin, 2007) found no clear relationship between the publication of a financial stability report and financial stability. On the other hand, Born and others (2011) provide some evidence that central bank communication on financial stability may reduce market volatility.

So, are these reports good for anything? In a recent paper with Sònia Muñoz, Shakira Teh Sharifuddin, and Kalin Tintchev, we re-visit the experience with central banks’ financial stability reports in light of the experience during the global financial crisis. Before I proceed further, let me stress that the views expressed in this paper are ours and do not necessarily represent those of the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. Let me now highlight three elements of our analysis.

First, expanding on my earlier study on the subject, we compile a comprehensive, world-wide database of stability reports, and we analyze whether simply publishing a financial stability report, as opposed to not publishing such a report, is associated with any difference in financial stability. We examine 132 countries, both those that published a stability report in 2000–09 and those that did not. To measure financial stability, we use several proxy variables, including a binary variable (crisis versus no crisis) based on the Laeven and Valencia (2008) dataset of systemic banking crisis, Moody's Bank Financial Strength Ratings, a measure of volatility of the national stock market, the International Country Risk Guide sovereign financial risk rating, and 1-year median banking system Expected Default Frequency calculated by Moody’s KMV. Our results, which are rather robust with respect to these different measures of stability, show no statistically significant difference in financial stability associated with publishing a financial stability report. In other words, simply publishing a financial stability report, as opposed to not publishing, seems to make little or no difference in terms of financial stability.

Second — because not all stability reports are created equal —we try to see whether there is a link between specific features of the report and financial stability. To do this, we dissect each of the financial stability reports into five key constituent elements, identified in previous work, namely:

- aims of the report;

- its overall assessment of financial stability;

- issues covered by the report;

- the underlying data, assumptions, and tools; and,

- the report’s structure and other issues.

For each of these five elements of the report, we examine three characteristics, namely clarity, consistency, and coverage. The identification of these “three Cs” as key characteristics of a good report is not new. It comes from Čihák (2006), which in turn builds on an earlier study of central banks’ inflation reports, which found that better-written inflation reports result in a more predictable monetary policy (approximated via inflation expectations). To limit subjectivity (and also to make it easier to process such a large number of reports), the methodology focuses on elements and characteristics that can be relatively easily observed and established, such as whether the report’s aims are explicitly stated, whether it contains an explicit definition of financial stability, whether it includes stress test results, whether it is accompanied by underlying data in an accessible format (e.g., in an Excel file posted on the website), and so on. Based on these five elements and three characteristics, we construct a “rating” for a subsample of 44 countries during 2000–09. Interestingly, we find that higher-quality reports—those that do relatively better than other reports in terms of clarity, consistency, and coverage—are associated with more stable financial environments.

Third, we zoom in on a smaller sub-sample of eight countries that publish financial stability reports, namely Brazil, Canada, Korea, Iceland, Latvia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Spain, and we look more closely at the substance of what these reports said in recent years, namely from 2008 to mid-2011. These eight countries were selected with a view to having a reasonably balanced coverage (geographically, between advanced economies and emerging markets, and also between countries that both felt the brunt of the global financial crisis and those that were relatively unaffected). The case studies confirm that the financial stability reports, despite some improvements in recent years, still tend to leave much to be desired in terms of their clarity, coverage of key risks, and consistency over time. A major drawback of a number of these reports is their lack of ‘forward-lookingness’, that is, insufficient analysis of risks and vulnerabilities. This makes them less capable of assessing systemic risk. We also find other common drawbacks, such as insufficient analysis of interconnectedness among financial institutions, lack of access to the underlying data for the report, and a failure to communicate clearly important gaps or weaknesses in the underlying data.

What is the bottom line of our analysis? What are the financial stability reports good for? In contrast to the well-known song, our answer is far from “absolutely nothing”. In fact, our answer is a qualified “yes”: such reports can have a positive impact on financial stability, but only if they are written well. There is only a weak empirical link between financial stability report publication per se and financial stability. In other words, there is room for improvement in terms of the quality of financial stability reports.

References:

Born, B., Ehrmann,M. and M. Fratzscher, 2011, "Central Bank Communication on Financial Stability", ECB Working Paper No. 1332 (Frankfurt: European Central Bank).

Čihák, M., 2006, “How Do Central Banks Write on Financial Stability?", IMF Working Paper No. 06/163 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Fracasso, F., Genberg, H. and C. Wyplosz, 2003, "How do Central Banks Write? An Evaluation of Inflation Reports by Inflation Targeting Central Banks", Geneva Reports on the World Economy, Special Report 2.

Laeven, L. and F. Valencia, 2008, “Systemic Banking Crises: A New Database,” IMF Working Paper 08/224 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Oosterloo, S., J. de Haan, and R. Jong-A-Pin, 2007, "Financial Stability Reviews: A First Empirical Analysis", Journal of Financial Stability, No. 2, pp. 337–355.

Further reading:

Čihák, M., S. Muñoz, S. Teh Sharifuddin, and K. Tintchev, 2012, “Financial Stability Reports: What Are They Good For?”, IMF Working Paper No. 12/1 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Join the Conversation