People's Bank of China front view. | shutterstock.com

People's Bank of China front view. | shutterstock.com

As World Bank economists, we are often asked by our clients about the lessons from China for development. Mostly, these questions relate to how China was able to transform its economy and grow so rapidly since its opening-up policy started in 1978. Although these are difficult questions to answer, there is a wide range analysis out there for reference (for example, Diop 2013; Dollar 2008; Flassbeck el al. 2005). A few years ago, we started receiving questions from clients on what lessons there were from China’s monetary policy during the period of transition. We tried to answer these by looking at Chinese monetary policy conduct between 1987 (the first year with reliable consumer price index data) and 2006 (the year the de facto fixed exchange rate of the renminbi was abolished). The following is a summary of what we found. For more details, see World Bank (2016, 11-20).

Operational independence of the central bank mattered

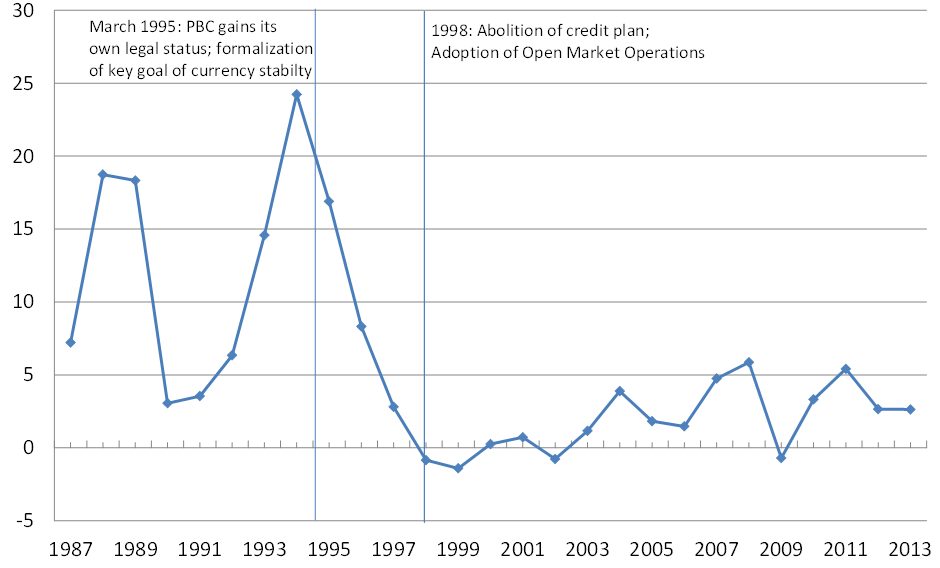

China was able to change from a high and volatile to a low and stable inflation environment between the 1980s and the 1990s due to reforms that established the operational independence of the People’s Bank of China (PBC). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, China experienced high and volatile inflation—reaching 19% in 1988 and 24% in 1994 (figure 1a). However, inflation fell over 1995–98, and it has been low and relatively stable since. This change in fortunes was made possible by several reforms in the mid-1990s that allowed the PBC to move toward greater operational independence—by establishing the PBC as its own entity under the State Council (1995)—and to end the credit plan (1998), with a greater focus on inflation as well as significant changes in China’s exchange rate policy. While the PBC was much more independent after the 1995 reform, it was far from fully legally or operationally independent. Only two of seven monetary policy instruments in use during the period did not require State Council approval (Geiger 2010). Yet, after the reforms, money supply growth stabilized, which reduced the rate and volatility of inflation, indicating that inflation was largely a monetary phenomenon at the time (figure 1b).

A nominal anchor provided stability during the reform period

Changes in China’s exchange rate policy were an important complement to institutional reforms. The changes in exchange rate policy had two main components: (i) depreciation of the official exchange rate against the U.S. dollar by 33% in 1994 (figure 1c), and (ii) harmonization of the market-based “swap center” exchange rate and the official exchange rate (Mehran et al. 1996). In 1993, around 80% of foreign exchange transactions were conducted in swap centers in different regions of China (Xu 2000), and the swap rate was much higher than the official rate—and had been so since the mid-to-late 1980s (Mehran et al. 1996, chart 12). The large 1994 devaluation was not the first: the renminbi was devalued by 21% in December 1989, and by 17% over 1990–93 in several smaller steps. These devaluations were smaller than the change in the consumer price index over the previous couple of years and the inflation gap with the United States, and so aimed to bring the real exchange rate closer to its equilibrium value rather than undervaluing it.

The devaluation set the stage for a fixed exchange rate to serve as a nominal anchor for China over the following decade. The rate was established at around 8.3 RMB/US$. The size of the 1994 devaluation also helped in stabilizing the renminbi: after the 1994 devaluation, the renminbi appreciated slightly against the dollar over the following two years, reversing the trend of regular devaluation since 1980. The stabilization of the renminbi no doubt had the effect of lowering (and stabilizing) inflation expectations, which had been building in response to the inflation outbreaks of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Together with the institutional reforms, the exchange rate policy of the early 1990s was able to lay the foundation for remarkable inflation stability over the next decade.

Figure 1: Inflation, Broad Money Growth, and the Exchange Rate during China’s Transition

a) Inflation rate, annual, %

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Note: (c) An increase represents an appreciation of the renminbi.

Join the Conversation