Landscape with ECB in the background | pixabay.com

Landscape with ECB in the background | pixabay.com

Does monetary policy influence the maturity structure of corporate debt? That is, do changes in the monetary policy stance alter non-financial firms’ incentives to issue short- versus long-term debt? Which companies eventually change their debt maturity more sharply?

These questions are important for many reasons. Rising levels of corporate debt represent a key source of vulnerability for economies, as highlighted by policy makers like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. In this respect, debt maturity is a key attribute in explaining firms’ responses to different types of shocks—including the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic (Fahlenbrach et al. 2020)—and their ability to recover following economic and financial downturns. Hence, understanding whether central banks influence firms’ relative reliance on short- versus long-term debt may reveal a potentially relevant and unintended aspect of their policies on firm risk.

Despite the relevance of the question at hand, no other study systematically investigates the impact of monetary policy shocks on corporate debt maturity structure. Our paper contributes by establishing novel (aggregate and cross-sectional) empirical facts and proposing a mechanism that explains them.

Our results have policy implications that are discussed at the end of this blog.

Our paper

We disentangle the effect of monetary policy on the maturity structure of corporate debt by investigating data for the US non-financial corporate sector over 1990–2017.

In particular, consistently throughout the time-series and firm-level empirical analysis, we focus on the share of long-term debt, identified as the percentage of debt with outstanding maturity greater than one year. We gathered time-series data from the Federal Reserve Board’s (FED’s) Flows of Funds, following Greenwood et al. (2010), and firm-level balance sheet data for listed non-financial firms from Compustat.

As a proxy for monetary policy shocks, our baseline analysis employs the simple quarterly variation in the effective federal funds rate. However, we verify the robustness of our findings to using other exogenous shocks based on high-frequency identification.

We estimate the dynamic response of the share of long-term debt to monetary policy shocks through local projections (Jordá 2005).

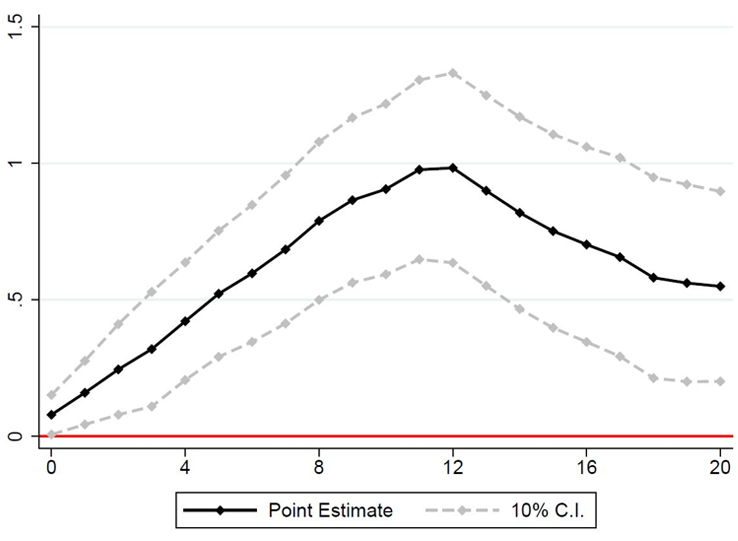

Figure 1 depicts the impulse response stemming from the time-series analysis, calibrated to a 25 basis points quarterly reduction of the policy rate by the FED. Evidently, following a policy rate cut, the share of long-term debt increases. The adjustment is persistent and economically large, amounting to 0.42 percentage point (p.p.) one year after the shock. For comparison, the average quarterly growth rate of the share of long-term debt is 0.15 p.p. Put differently, monetary policy explains a significant fraction of the variation in non-financial firms’ relative reliance on short- versus long-term debt.

Figure 1: Response of the share of long-term debt to a monetary policy shock

The figure reports the impulse response function of the share of long-term debt to a 25 basis points policy rate cut.

Next, we investigate firm-level data to gauge eventual cross-sectional differences in firms’ adjustment. We again use local projections, although in a panel data framework, and allow for different firm-level channels to drive our findings. Namely, we “horse race” asset size, financial leverage, liquid assets, and firm profitability.

It turns out that the heterogeneity in firm adjustment is mostly driven by asset size. Contrary to traditional models of monetary policy transmission—predicting that small companies adjust their capital structure relatively more in reaction to interest rate shocks—we find that very large companies are responsible for the aggregate patterns.

This can be seen in figure 2, where we report impulse response functions estimated within different groups of listed companies, sorted depending on the respective industry-level asset size quartile. Only firms in the upper quartile of the asset size distribution increase their relative reliance on long-term debt, whereas smaller firms are generally unaffected. In further analysis, we show that the adjustments are driven by changes in long-term debt by those large firms.

Figure 2. Response of the share of long-term debt to a monetary policy shock across companies of different sizes

The figure reports the impulse response function of the share of long-term debt to a 25 basis points policy rate cut across different groups of non-financial listed companies, sorted according to industry-level asset size quartiles.

Why do such big, arguably unconstrained companies increase long-term debt and change their debt maturity structure when monetary policy loosens?

We propose a theory that encompasses firm-level financing frictions due to moral hazard and the presence of yield-seeking investors (Hanson and Stein 2015) who reach for yield, meaning that they increase demand for risky long-term bonds when the policy rate falls, to maintain their portfolio yield. Only large, unconstrained companies can take advantage of this demand shift by issuing long-term bonds, in line with our empirical facts.

Our work concludes with few empirical tests on the model’s main mechanism. In particular, in line with our theory, we find that reaching for yield by corporate bond mutual funds (Choi and Kronlund 2018) is associated with a larger jump in corporate bond holdings and a boost in portfolio maturity following an interest rate loosening. Likewise, in line with the prediction that large firms’ relative response is driven by increase in demand by financial investors, we find not only that large firms increase the issuance of long-term bonds, but also such issuance benefits from relatively lower financing costs (compared with small firms).

Policy implications

Our work has the following policy implications:

- Prolonged periods of low interest rates have the unintended consequence of piling up huge amounts of long-term debt in large firms’ balance sheets, with potentially serious debt overhang dynamics as a legacy (Gomes et al. 2016; Kalemli-Ozcan et al. 2018).

- The reach-for-yield channel favors large firms, which dominate the bond market and are unlikely to increase investment and/or employment through the debt channel (see, for example, Elgouacem and Zago 2019). Hence, this channel may not have significant effects on the real economy.

Most advanced economies have experienced very low interest rates over the past decade. Given the unprecedented contractionary forces released by the Covid-19 pandemic, low rates are likely to remain for the foreseeable future. While in this policy environment the traditional bank-centered monetary policy transmission may be hampered (see, for example, Brunnermeier and Koby 2018), the reach-for-yield channel is likely to be exacerbated, which ultimately raises doubts about the effectiveness of further monetary expansion in stimulating recovery.

We leave this question for future research.

Andrea Fabiani (@AndreaFabiani89) is a PhD candidate in Economics at Universitat Pompeu Fabra & Barcelona GSE. More details about his research can be found on his website.

References

Brunnermeier, M. K., & Koby, Y. (2018). The reversal interest rate (No. w25406). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Choi, J., & Kronlund, M. (2018). Reaching for yield in corporate bond mutual funds. Review of Financial Studies, 31(5), 1930-1965.

Elgouacem, A., & Zago, R. (2019). Share Buybacks, Monetary Policy and the Cost of Debt (No. w773). Banque de France.

Fahlenbrach, R., Rageth, K., & Stulz, R. M. (2020). How valuable is financial flexibility when revenue stops? Evidence from the Covid-19 crisis (No. w27106). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gomes, J., Jermann, U., & Schmid, L. (2016). Sticky leverage. American Economic Review, 106(12), 3800-3828.

Greenwood, R., Hanson, S., & Stein, J. C. (2010). A gap‐filling theory of corporate debt maturity choice. Journal of Finance, 65(3), 993-1028.

Gürkaynak, R. S., Sack, B., & Swansonc, E. T. (2005). Do actions speak louder than words? The response of asset prices to monetary policy actions and statements. International Journal of Central Banking.

Hanson, S. G., & Stein, J. C. (2015). Monetary policy and long-term real rates. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(3), 429-448.

Jarociński, M., & Karadi, P. (2020). Deconstructing monetary policy surprises—The role of information shocks. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 12(2), 1-43.

Jordà, Ò. (2005). Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. American Economic Review, 95(1), 161-182.

Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Laeven, L., & Moreno, D. (2018). Debt overhang, rollover risk, and corporate investment: Evidence from the European crisis (No. w24555). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Join the Conversation